The only time I actually met Albert Finney, I was wearing an enormous cartwheel hat and chalk-white face paint and he was being propositioned by a stripper. Full disclosure, we were on the set of the period film Washington Square (1997); it was my first time working on a movie. I’d bluffed my way into a union voucher by lying about my years of dance training. It was utterly worth the deception, though, because not only was I working, I was mere feet away from this man I’d long worshipped on screen.

My adoration, however, was interrupted by this other background artist, which is the nice name for extras (far kinder than “breathing furniture”) who sashayed over while the next shot was set up. She wanted to let Mr. Finney and anyone else in the vicinity know where she’d be working the pole later that evening and invite him to stop on by for a dance. He was as polite and respectful in his decline as if she’d asked him to please read her screenplay.

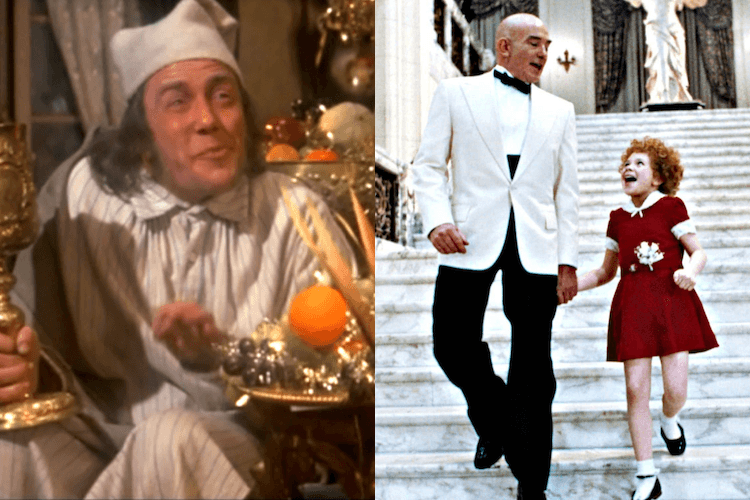

Not that I expected any less. I hadn’t yet spent enough time on movie sets to know that star behavior was often less than twinkly, especially toward those whose ranks were non-celestial, but his kindness elevated him even further in my estimation. I’d admired him in many roles, from Barry Lyndon (1975) to Erin Brockovich (2000) to Big Fish (2003), but two musicals made defining memories for me: Scrooge (1970) and Annie (1982).

Scrooge is hard to find on TV now. People usually think you mean the Bill Murray one, and when you say, “No, the one with Albert Finney,” they look at you oddly. It only airs a couple of times during the holiday season, usually at 3:30 a.m. or a similarly dismal viewing time. I finally broke down and bought it on DVD because I got tired of stalking it on late-night cable. When I was growing up, my mom used to bring our small black-and-white TV downstairs so we could watch the movie while we decorated our tree.

Scrooge is hard to find on TV now. People usually think you mean the Bill Murray one, and when you say, “No, the one with Albert Finney,” they look at you oddly. It only airs a couple of times during the holiday season, usually at 3:30 a.m. or a similarly dismal viewing time. I finally broke down and bought it on DVD because I got tired of stalking it on late-night cable. When I was growing up, my mom used to bring our small black-and-white TV downstairs so we could watch the movie while we decorated our tree.

While the Tinsel Wars raged between my parents (Mom was a placer and Dad was a thrower, which really summed up the marital situation right there), Albert Finney transported us to a magical, musical world of holiday redemption. He moved through Scrooge’s story effortlessly, the older, grizzled Ebenezer just as believable as the youthful and, it must be said, hot one. It became my defining interpretation of A Christmas Carol, the one I insist on watching annually, singing along while my children cringe next to me.

I sang along to Annie before I ever saw the movie; we had the record of the original cast album and I knew the words to every one of the songs. I knew Finney as Scrooge, so I was less than completely sold on him as Daddy Warbucks, but I decided that I was willing to suspend judgment. The movie was bright, colorful, and featured an incredible cast — even as a kid, I could appreciate Carol Burnett, and Ann Reinking was the embodiment of cool grace — but it wasn’t life-changing. At least, not directly.

I sang along to Annie before I ever saw the movie; we had the record of the original cast album and I knew the words to every one of the songs. I knew Finney as Scrooge, so I was less than completely sold on him as Daddy Warbucks, but I decided that I was willing to suspend judgment. The movie was bright, colorful, and featured an incredible cast — even as a kid, I could appreciate Carol Burnett, and Ann Reinking was the embodiment of cool grace — but it wasn’t life-changing. At least, not directly.

My sister, Michell, was a kid in a Catholic orphanage when she first saw Annie. If it seems like maybe an odd choice for the nuns to take kids to see this fairytale of an adoption fantasy — I see your point. But Michell loved it. She was plucky, resilient, and resourceful like Annie. She had freckles and reddish hair. So what if she was already a teenager? If it could happen for that kid, why not for her? Not long afterward, her social worker brought her to meet us at an open-air summer theater. The show they were performing was Annie. Michell saw it as a sign that her story was about to change.

She watched it every time it was on TV; later, of course, she bought it on VHS and then DVD. She watched it when she hadn’t seen it for a while, or when she felt nostalgic, or just when she needed a lift. She loved its message of relentless optimism and inevitable belonging. She was, ultimately, adopted herself and I think she liked reflecting on how far she’d come — her own Annie-style triumph.

My first movie, my holiday stand-by, my sister’s manifesto — how unlikely for those connections to all stem from one man’s work. He didn’t know me, and I didn’t have any deep personal connection to him, but those movies were significant for me. I think art that creates heartfelt meaning becomes a record — a way of living on through what we receive from the creation. As a former actor myself, I like to believe that Mr. Finney, who died on Feb. 7, would appreciate what Scrooge and Annie gave us: memories built around his efforts, hope when it was occasionally in short supply, and a living example of keeping it classy. To my way of thinking, that’s a pretty magnificent legacy.