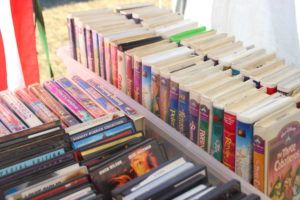

“Anything in particular you lookin’ for?” The old woman in the lawn chair asked with more exasperation than curiosity. I stood over a box of plastic clamshell VHS cases, the kind usually reserved for Disney movies, the kind that makes a primally satisfying pop when opened, and lied.

“No, not really.” In fact, I was looking for Universal Studios Florida: Experience the Magic of Movies, a souvenir video last seen somewhere in 1994, but that’s not something one admits to strangers. “Thank you, though,” I added, systematically shuffling the top layer of tapes – Disney – to peek at what might hide beneath – mostly Disney.

“We don’t have Lion King, if that’s what you’re after.” She watched me from over a table of rusting tools and only moved to get a better look. Her husband, sitting alongside in an identical chair, didn’t move at all. The grassy lot pock-marked with mud and tents sat a few feet up and a few feet over from Highway 127, and he watched that road like the Kentucky ground might suddenly swallow it whole.

“A lot of demand for Lion King this weekend?” She grimaced and faced the highway with her husband. In any movie, her answer would’ve been leaden with philosophical import, and to her credit, she delivered it with undue gravitas, wheezing desperation. In reality, it was too mundanely stupid to be anything more than a genuine complaint.

“Everyone’s lookin’ for Lion King.” Her husband stirred just enough to hum in agreement, eyes still stuck under the brim of his mesh-backed Coors cap.

Thanks to a recklessly misleading BuzzFeed list, too many enterprising resellers think certain Disney VHS tapes are worth small fortunes. The average Lion King listing on eBay ranges anywhere from $200 to a brand new Ford Fiesta. Of course, nobody bids on those; they go for the $5.50 Buy It Nows hiding in between. At the next stop on my trip, I found a clamshell copy of Lion King for a dollar. At the stop after that, I found another for $8, with a handy sticker reminding me it was “RARE.”

In a roadside plot just outside Danville (“Quite Possibly the Nicest Town”), a day deep in the World’s Longest Yard Sale and running on a gas station breakfast, I realized nobody knows what the hell to do with VHS tapes. Are they worth much in dollars and cents? Are they worth much in nostalgia? Are they worth much at all?

What better place to figure it out than The World’s Longest Yard Sale, where it’s a hard $3 on the McDonald’s Garfield mugs from 1987, but you can haggle for the same seller’s plane fuselage. The sale, now 30 years running, stretches from the thumb of Michigan to the middle of Alabama — 690 miles of tents, tarps, and flatbeds full of what many vendors would be the first to call junk. It carries an affectionate detachment — far enough removed from want, interest, or personal connection, everything’s a McDonald’s Garfield mug from 1987. But it’s also dangerously subjective. Anything blessed with the divine stamp of Coca-Cola demands a higher price and little room to maneuver, even if it’s just the blue plastic cup I got for an extra 25 cents from the Chinese place in the mall. Happy Meal toys are barely worth the plastic they’re molded from, but that doesn’t stop some intrepid sellers from putting that two-inch-tall Mickey Mouse figure from 1994 in a plastic bag with a $10 price tag and warning to “HANDLE WITH CARE – OLD!”

That false inflation of age doesn’t quite reach VHS tapes. Everyone seemed to agree they’re not old-antique so much as old-obsolete. Almost every seller with more than just furniture or a cardboard maze of Chinese knockoffs had a tape or two lurking around, one of which was always Jerry Maguire. They’re clutter, no different from the Dixie Stampede boot cups and ungently used tee-ball bats surrounding them. At a quarter, priced to move. Priced for someone like me.

I use VHS tapes like most people use Netflix. Streaming services offer respectable libraries of movies, if not as respectable as they used to be. But there are limits and leanings — only a select number at any given time, good luck finding anything from the unrecorded wastes of pre-1982. With VHS tapes, now competitively priced against gumballs, I can pick up a movie I’ve never even heard of that might not have survived the great culling of DVD.

Horror took that blow the hardest. The 1980s direct-to-video boom provided refuge for the low-budget slashers too cheap, gory, or otherwise indistinct to breach the multiplexes. The ever-adaptive Roger Corman caught on early and held on tight, still producing almost exclusively direct-to-DVD today. This niche of video-store horror attracted hungry gorehounds through immediately memorable, mostly dishonest box art still celebrated today, more than some of the actual movies represented. Maybe the flick doesn’t feature the impossibly expensive monster on the box, but who cares — it’s already been paid for. When shiny, new, expensive DVD arrived, a lot of these rental store refugees never made the jump.

These are the tapes that go for prices Lion King can only dream of. And from what I could tell, collectors had trawled most of them by the time I passed through.

I was taking a picture of a shoulder-high shelf full of VHS tapes ominously balanced on the edge of a hill when the seller caught me.

“I’ll only charge a little for pictures.” I turned around to catch him laughing at his own joke, arms threaded through the straps of his overalls. I told him I appreciated the discount, but I just had a VHS problem. He tweaked at his steel wool beard and like a magician out of a Marlboro ad produced four tubs of tapes he wasn’t selling enough shelves to display. Almost immediately, he offered to sell me the entire haul at half-price. Told me he’d been amassing the lot his whole life. Told his wife if he didn’t sell them all he’d watch a movie a night for the rest of his life. “And you know what?” he asked me. “I b’lieve I could do it.”

Others picked through it, he told me, and the collection showed the signs. A lot of standards — Top Gun, City Slickers, assorted Home Alones — and a few off-beat horror movies harder to come by. After another sales pitch for the whole kit and caboodle — “one-fifty and I’ll carry ‘em all to your car” — I walked away with a copy of C.H.U.D., that is “Cannibalistic Humanoid Underground Dweller,” that doubled as a historical document. According to the smeared stamp on the label, it was rented out of an E-Z Stop Food Mart, before being liberated by Norma Catterton, who saw fit to sign her name once and initial twice.

The next horror movie I looked at wasn’t so well loved.

It rained early Saturday morning and by the time the garage sales woke up, dirt turned to mud and junk turned to soggy junk. Glassware survives and, if nothing else, proves its utility. Old electronics, traditionally, don’t. A Jenga tower of VHS tapes, one move away from disaster, sat threateningly near the three-foot-high edge of a flatbed. There was still all of Sunday to sell, but the woman with a fanny pack full of change promised deep discounts. She, too, offered me her entire stack of movies for an unspecified bargain. So I dug, playing the most dangerous game (of Jenga) for Friday the 13th Part VI: Jason Lives, hiding in the plastic bin at the bottom. I won. And I’d never seen a moldy VHS tape before. A crawling white growth bound the left reel and seemed to be eying the right.

VHS tapes hide their sensitive bits on the inside, unlike DVDs, which are all sensitive bits, but they’re hardly indestructible. Their closest cousin, inevitably found baking in the sun at the end of the same table and slowly curling into one of those trendy bowls the natural way, is the LP record. Turntables dig a little deeper into the grooves with every play. Each rewind of Forrest Gump wears out the reels, the magnetic tape ever so slightly. The actual quality is outdated by decades and outclassed by several generations of format. The most frequent buyer anymore does so to scratch a nostalgic itch. Anyone who tells you records “sound warmer” is not to be trusted. Records and VHS tapes were gateway drugs, the first home media in their respective arts to catch the public and not let go. Those horrors left behind have traumatized more sleepovers and inspired more artists than some movies to actually see the inside of a theater. The volume of records, of tapes produced and put into service is staggering. The big difference is that vinyl, if it’s anything short of worn through, only sounds rough next to a modern master.

The limits of VHS are apparent as soon as the FBI warning. Pan-and-scan, that most dreaded of video-based rhymes that afflicts all but a few late-game tapes, was a destructive solution to a simple problem — movies were rectangular, TVs were almost square — that resulted in a truncated image with the sides cut off. VHS audio runs anywhere from distant to hollow when the hiss isn’t choking it. It also bears reminding that VHS requires an extra purchase at Radio Shack just to rewind with any sort of haste.

VHS tapes are a tangibly worse format than anything that followed. Even Laserdiscs, while prone to the heinous-sounding disc rot, carried most movies in their proper aspect ratios. They don’t carry the distinctly different quality of records, so much as a distinctly cruder quality.

But you’ll never see a home-burned DVD double feature of The Country Bears and Signs. That particular tape, committed to a Maxell High Grade, was buried in a box in the “Golf Capital of Tennessee.” Maybe it was just an admirable commitment to tape economy, genre and thematic compatibility be damned. Or perhaps a sadistic way to teach the kids to rewind their movies when they’re done watching them. Or an experiment in repressed memories involving bears. It still haunts me and I will regret not buying that tape for some time.

And there’s the worthless value of VHS. We’re never going to see another universally embraced home video format again, at least not a physical one. Not one you can throw in at a moment’s notice to tape the Sunday Night Movie. Trailers didn’t have teasers and teaser-teasers, each carried by all major movie news outlets. All you had were the handful of previews before the feature presentation, sometimes with a montage of a studio’s loosely collected re-releases; I remember moments from Prehysteria, a movie I’ve never seen, because of clips from Paramount’s Family Favorites promo. Was it bald advertising? The baldest, but it was also a mysterious little window into the wide world of motion pictures before the internet became one enormous, blinding window.

When I walked by that flatbed again, the moldy tapes were gone. Someone bought the lot. I could only speculate why – maybe they had a problem, too. But it didn’t surprise me. Every outpost on 127 has dusty crates full of John Wayne movies. Just outside Cincinnati someone’s still trying to get $10 for their copy of The Lost World: Jurassic Park, one of the top-selling tapes ever made by Spielbergian default. A vendor farther south sold tapes for a dollar apiece or double-packs for three, despite most VHS double-packs forming two halves of the same single movie. VHS tapes aren’t worth fortunes, even small ones. They take up more space than just about any other possible format. If we’re getting superficial, the movies contained end up fuzzy and compromised.

But they stick around as chunky reminders of a time we’ll never see again. When “home video” was a novelty and more than justified a trip to Blockbuster. And even though Beta, Videodisc, and Laserdisc had their faithful flocks, the common tongue was VHS, and those black bars were a small price to pay for turning the family room into a movie theater for an hour and a half.

Nostalgic, obsolete or worthless, I’ll still buy that for a dollar.

P.S. If anyone finds a copy of Universal Studios Florida: Experience the Magic of Movies, mail it to Crooked Marquee, c/o Jeremy Herbert. Rewound if possible.

Jeremy Herbert adjusts his own tracking in Cleveland.