I recently read somewhere that The Sting is the oldest movie on Netflix. Like most things you read on the internet, this turned out not to be true. (My editor informs me that Night of the Living Dead and a handful of older Indian films are also currently on there.) But for a service that tends not to bother streaming movies older than Leonardo DiCaprio’s girlfriends, the inclusion of director George Roy Hill’s 1973 caper comedy is a sign of just how beloved it is. (Either that or the licensing was cheap, which seems unlikely given the movie’s reputation.) When I was growing up in the ‘80s, The Sting was already talked about as an all-timer, one of those “they don’t make ‘em like that anymore” movies that epitomizes Hollywood doing what Hollywood used to do best.

A crowd-pleasing blockbuster that won seven Oscars including Best Picture, The Sting must have seemed like quite the balm during that tumultuous Watergate winter. Its competition at the box office included Serpico, The Last Detail, Cries and Whispers, Magnum Force and The Exorcist, so you can see why The Sting’s soothing, old-timey charms felt like sweet relief. It’s a movie without a care in the world beyond showing the audience a good time. Suffused with a gentle, trickster spirit, the picture’s rose-tinted, Depression era Americana and idealized notions of honor among thieves are even bigger cons than the one pulled off by the protagonists. But we in the audience are willing marks.

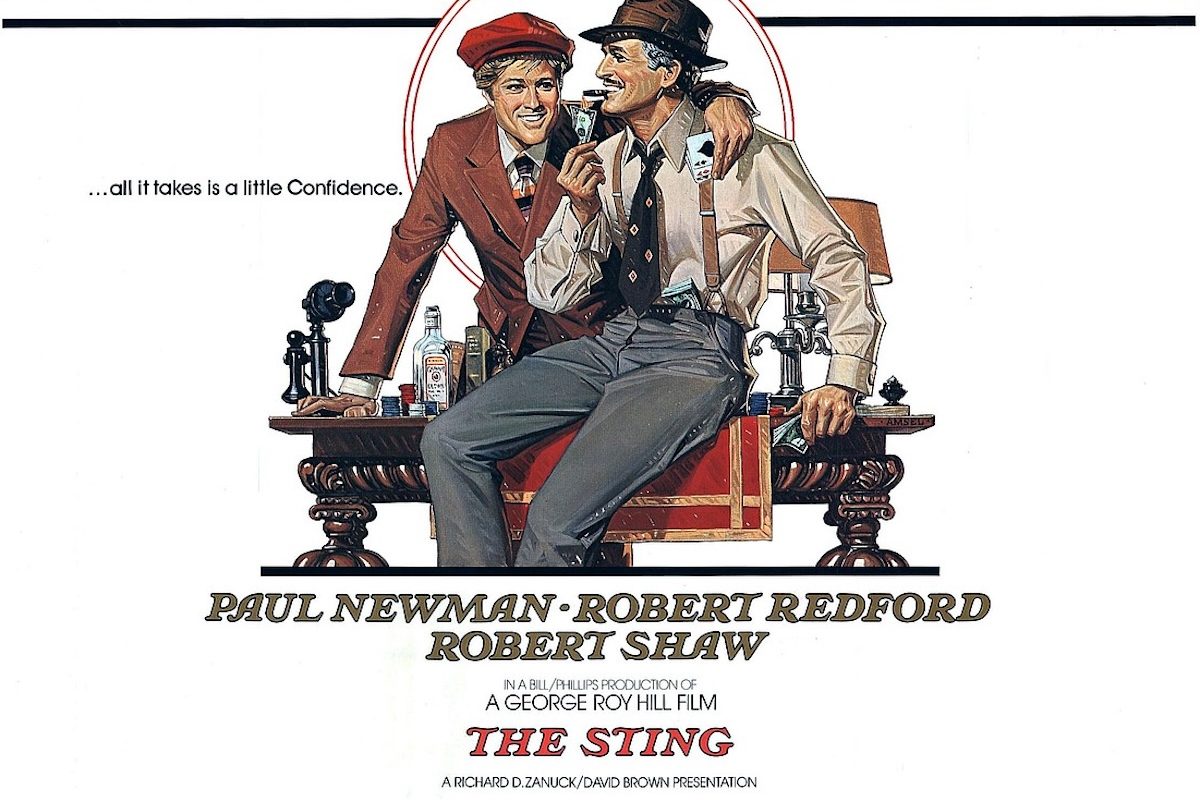

The Sting reteamed Robert Redford and Paul Newman with their Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid director George Roy Hill, and it’s easy see the movie as a spiritual sequel to that 1969 blockbuster, playing on the inimitable chemistry of these singular onscreen icons and lifelong offscreen friends. (On one hand, it’s disappointing that Newman and Redford only ever made two pictures together, though looking at those dire twilight years of the Lemmon and Matthau partnership, maybe it’s for the best.) They’ve swapped mustaches this time, as well as their positions in the Hollywood pecking order. During the four years since Butch Cassidy became a sensation, Redford had rocketed to superstar status while Newman appeared in a string of flops. Despite billing to the contrary, the former Sundance Kid is clearly The Sting’s protagonist and his partner is playing a beefed-up supporting part.

In a tradition that would carry on throughout his career, the then-37-year-old Redford was about 15 or 20 years too old for the role of Jimmy Hooker, an ambitious street kid running small time scams who’s introduced to the world of big time cons after his mentor (Robert Earl Jones, James’ dad) is killed by the minions of Robert Shaw’s ruthless bootlegger, Doyle Lonnergan. Jimmy wants to avenge his friend by hitting the Irish bastard where it hurts – in the wallet – enlisting Newman’s legendary conman and washed-out drunkard Henry Gondorff to show him how. Soon, half the Chicago underworld is in on their scheme to build a fake off-track betting parlor in a swindle that plays things straight with the audience about two-thirds of the time. Then come the surprises.

The twists and turns presumably seemed more novel 53 years ago, when hustles and con games were still fresh territory for films. I assumed that the Ocean’s movies and David Mamet’s entire screen career had made contemporary viewers less susceptible to such trickery, but a couple of audible gasps at a recent screening I attended during the Brattle Theatre’s Tribute to Robert Redford suggest The Sting can still pull the wool over some audiences’ eyes.

Honestly, I find all the plot stuff extraneous to the film’s breezy pleasures. The fun is in watching great faces giving each other sly nods, and Redford’s ability to play both gullible and knowing, often at the same time. Newman doesn’t appear until 26 minutes into the picture, at which point he seems to be launching the second and far more enjoyable phase of his career, relaxing into middle age as a rascally character actor. (“Sorry I’m late, I was taking a crap” is a great way to walk into a room.)

The Sting is far lighter on its feet than Butch Cassidy, with the added benefit of not having music that makes you want to jam a screwdriver into your eardrums. (Apologies to Burt Bacharach, but have you heard that score lately? Jesus.) Marvin Hamlisch’s reworking of Scott Joplin’s The Entertainer was inescapable when I was kid. The ragtime music is actually an anachronism; Joplin died in 1917, the film takes place in 1936. But no matter, as it evokes the movie’s fanciful approach to a make-believe underworld spun out of old movies and pixie dust. Pauline Kael called it “crooks as sweeties.” This is a Great Depression where even lowlifes are dressed to the nines in dapper Edith Head costumes, where you won’t find any rabble on these weirdly depopulated backlot streets, and where everyone is too cool to act like they’re in the slightest bit of danger. The Sting is both a grift and a great escape. It makes you nostalgic for something that never was.

“The Sting” is streaming on Netflix.