An interest in sex is common ground for most people, but not for me. There’s no onscreen depiction of sex that arouses me. It’s foreign at best and horrifying at worst. Why? Because I’m asexual.

Let’s clear a few things up first. No, being asexual is not the same thing as being celibate, and no, I can’t reproduce by budding. Asexuality is its own spectrum with a swath of variations: demisexuals are physically attracted to someone only after falling in love; greysexuals might be into someone every once in a blue moon. I identify as an aromantic asexual. I’ve never had a crush, been in love, or been sexually attracted to anyone. I’m fine with others having sex, but I’m repulsed by the idea of it involving me.

“That sounds like a non-issue,” you may think. It’s not, though — I still live in a culture where sex the norm. If anything, I see sex as a morbid curiosity. Some people are drawn to pimple-popping videos; I have sex scenes in films. The problem is that no one in movies shares my outlook. I never see myself represented, so instead of embracing the similarities between a protagonist and myself, I have to embrace the differences.

Oddly enough, the first movie that made me feel validated in my asexuality was Eyes Wide Shut — 159 minutes of cinematic blue-balling. When playing to the straight male majority, it skewers heteronormativity by conflating it with arrogance. By seeing it at 16 years old, it helped me realize and embrace my orientation.

The film is virtually perfect in every way, but its exploration of the male id is especially amusing. First, it doesn’t feel a need to depict its straight male protagonist as a hero. Bill (Tom Cruise) is a detestable character whose fragility adds to the film’s entertainment value. He’s the archetypal Straight Man — what the majority sees as an emblem of power, and something that I can never be. Throughout Eyes Wide Shut, we see him endure the awkwardness that sexual minorities feel, and as he comes across any obstacle, he uses cash and privilege like an unspoken cry of, “But this can’t happen to me!” It’s a satirical viewpoint rarely explored, and seeing the film allowed me to laugh at the majority for once.

When I saw the film for the first time, just those first seconds made me think I was in for something special. That feeling continued, too, as sex was treated like a prizeless game. In the world of Eyes Wide Shut, physical intimacy is like playing tag: Once you touch someone, you win. OK, cool, but is that it? … Oh, that is it? Well … what now?

Later, at the film’s turning point, a stoned-out-of-her-mind Alice reveals that she almost cheated on Bill. But it isn’t unfaithfulness that angers him: It’s that Alice could want someone else. It’s here that the film displays Bill’s misogyny for the first time as he labels women coy and domestic. Alice thankfully calls him out, but before the conversation can further digress, Bill is summoned to visit the daughter of a recently deceased client.

Upon his arrival, a grief-stricken Marion (Marie Richardson) throws herself at Bill. It’s a straight male fantasy — the emotionally vulnerable woman and the strong-willed Straight Man — but this take-me-now interaction is presented as ludicrous. Hell, even Bill doesn’t know what to. He doesn’t act like a doctor played by Hollywood’s hottest star; he acts like a kid at a middle school dance. The subversion sewn through these scenes relates sex with invasion, which is something I’d always felt. It’s especially rare for the Straight Man to rebuff others’ advances in movies, and sympathizing with that was unprecedented to me.

But Alice calls Bill and accidentally cockblocks him, so I don’t have to see that.

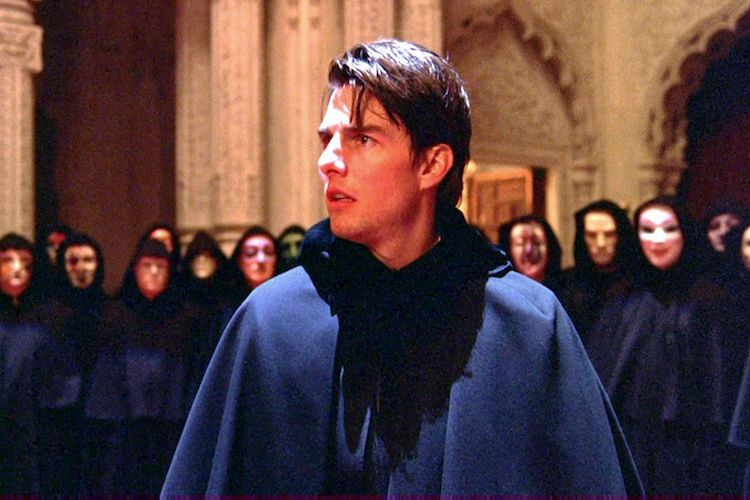

It all comes to a head in the ritual sequence, and in addition to being perfect filmmaking, it portrays sex the way I’ve always seen it. As a stripped-down redux of the earlier cocktail party, the rich are not only entitled to monetary belongings — they’re entitled to others’ bodies. The emotions associated with intimacy are nowhere to be found.

It’s such a heartbreaking concept: the sight of all these people, interchangeable and unable to communicate. An unknown woman approaches Bill and goes to kiss him, and after their masks keep them from embracing, they resort to wandering the halls of the rich. They remain unseen and unfulfilled. As I saw this for the first time, I felt both pity for their loneliness and resentment toward their power. But most importantly, for once I felt fulfilled for not wanting sex.

The orgy-goers look like bugs in a diorama, and as Bill proceeds through the mansion, the camera takes his point of view. It was then that I finally saw sex from the Straight Man’s perspective, and yet I still saw it with fear.

The scene disturbs a lot of people. It disturbs me too, but it’s also kind of comforting. This is how I always saw sex, and finally there was a time where I was in on the joke.

As I realized that I was asexual, I watched a masked man lead a blindfolded Nick (Todd Field) through a corridor of nude partygoers slow-dancing to “Strangers in the Night.” It was foreign, oddly fascinating, and something that I wanted no part in. After that scene, Nick was never seen again. And neither was the possibility of my being sexual.

‘the film displays Bill’s misogyny for the first time as he labels women coy and domestic.’

I don’t remember the words ‘coy’ or ‘domestic’, I remember him infuriating her by telling her that he trusts her. It’s not misogyny, it’s naivete. She has guilt, she has a desire to do something more adventurous than this monogomous marriage, their argument over nothing is partially just that she is high, like he says, but she can’t take this life which he thinks is pretty swell. He says he trusts her, she retorts that she would rather sleep with somebody else and give up her family, than to be trusted by him. That’s effed up man. Nasty. Who is the nasty one? But I see desperation, she wants to start a fight to shake things up, it’s kind of furtive.