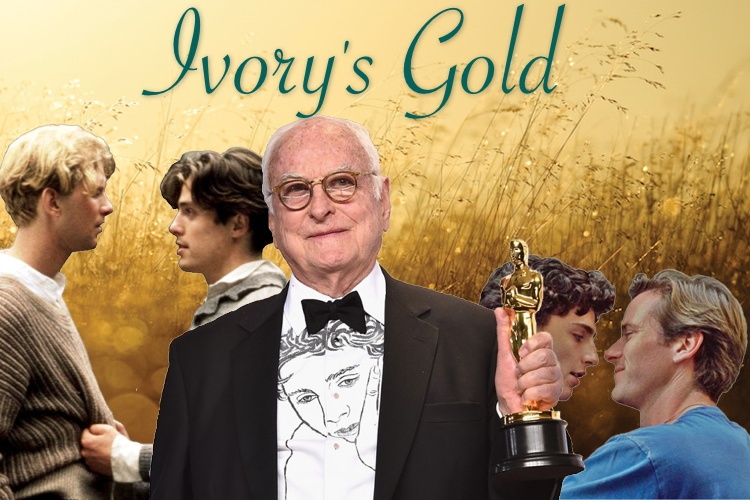

With his Best Adapted Screenplay win for Call Me by Your Name, James Ivory received some long-overdue recognition from the Academy. (He also became, at 89, the oldest winner in any category in Oscar history.) His prior nominations – all in the Best Director category – were for A Room with a View (1985), Howards End (1992), and The Remains of the Day (1993), three of the films that defined Merchant Ivory Productions in the public’s imagination. Together with producer Ismail Merchant and frequent screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, Ivory became synonymous with sumptuous literary adaptations, but he began honing his writing chops decades earlier, co-authoring three of the four features Merchant Ivory produced when they were based in India in the 1960s.

Ivory and Jhabvala based their scenario’s Buckingham Players on the real-life troupe headed up by Geoffrey Kendal and Laura Lidell, who play fictionalized versions of themselves, and featuring their teenage daughter Felicity, making her screen debut as its impressible ingénue, Lizzie. The film doubles as a coming-of-age tale for her since she falls for idle rich Indian Sanju (Shashi Kapoor, the husband in The Householder), who already has a lover in stuck-up Bollywood actress Manjula (future Merchant Ivory standby Madhur Jaffrey), who demonstrates the power of film over Shakespeare by upstaging a performance of Othello. And she’s not the only one troubled by Lizzie and Sanju’s relationship, as one of Ivory’s deep-focus shots reveals one of the Indian actors in Kendal’s troupe is plainly holding a torch for her. Rather than force the issue the way Manjula does, though, he chooses to keep his feelings to himself.

Along with the East/West contrast, The Guru includes its own variation on the scene where a serious artist is upstaged by a flashy entertainer. Here it’s Ustad who is upset by the screaming fans his inattentive disciple attracts. Meanwhile, Jenny’s resolve is tested when she learns her guru isn’t quite the holy man she expected. Finding out he has two wives (something permitted by his religion, but taboo in the culture she comes from) just doesn’t gibe with the image she had of him.

Fame is a double-edged sword, however, as Vikram discovers when he’s forced to sign on with a disreputable producer (played by The Guru’s Utpal Dutt) when his fortunes take a tumble. No matter how popular you are today, there’s always somebody waiting in the wings, ready to replace you at a moment’s notice – or a fickle producer’s whim. Witness the scene where Vikram attends a recording session for one of the musical numbers he’s going to be pantomiming in playback and spies his virtual double in the booth across the way. That sort of thing can’t inspire too much in the way of job security.

After Bombay Talkie, nearly two decades passed before Ivory received another screenplay credit, but he still found ways to keep his hand in. In addition to writing the narration for various Merchant Ivory documentaries (something he had experience with going back to his first short, 1957’s Venice: Theme and Variations), he also came up with the idea for 1972’s Savages, the team’s first American adventure, hashing out a treatment with George Swift Trow and Michael O’Donoghue (later of National Lampoon and Saturday Night Live), but leaving the actual scripting duties to them.

A similar situation arose a decade later when Ivory, Jhabvala, and Merchant all pitched in on 1983’s The Courtesans of Bombay, a docudrama that marked the feature directing debut of Merchant (who had made a half-hour short under the Merchant Ivory banner in 1974). Harking back to their Bombay films, Courtesans is a portrait of the Pavan Pool compound, which is home to female singers and dancers who support their families by plying a completely different trade after hours. Made for the UK’s Channel 4, the film alternates between three narrators: the property’s genial rent collector (and actual owner), a former resident played by actress Zohra Sehgal (who had previously appeared in The Guru and later had a role in Merchant’s The Mystic Masseur), and a frequent visitor played by Saeed Jaffrey, whose connection with the team went back to narrating Ivory’s 1959 documentary The Sword and the Flute and the Merchant-produced 1961 short The Creation of Woman. (The latter was the first film for which Merchant was nominated for an Academy Award. The second was 1985’s A Room with a View, which earned nominations for all three of Merchant Ivory’s pillars and Jhabvala her first of two Oscars.)

With their international stars and million-dollar budgets, A Soldier’s Daughter and Le Divorce seem far removed from Merchant Ivory’s humble beginnings scraping together financing in Delhi and Bombay, but they traffic in the same themes of cultures in collision and the role of the artist in society. Similarly, the convention-defying same-sex attraction of Maurice finds its counterparts in the doomed love affairs between English women and Indian men in Shakespeare Wallah and Bombay Talkie. And all of these films look ahead to Call Me by Your Name. Whether it’s Armie Hammer’s Oliver fretting over whether he’s “ruined” his host’s teenage son and worrying they may pay for what they’ve done, or Timothée Chalamet’s Elio experiencing disillusionment comparable to Lizzie in Shakespeare-Wallah or Jenny in The Guru, or Michael Stuhlbarg’s Samuel pining for the love he might have had under different circumstances (much like Clive does at the end of Maurice), Call Me’s characters reveal their fragility and humanity in ways Ivory has been doing consistently for six decades and counting.

Join our mailing list! Follow on Twitter! Like us on Facebook!