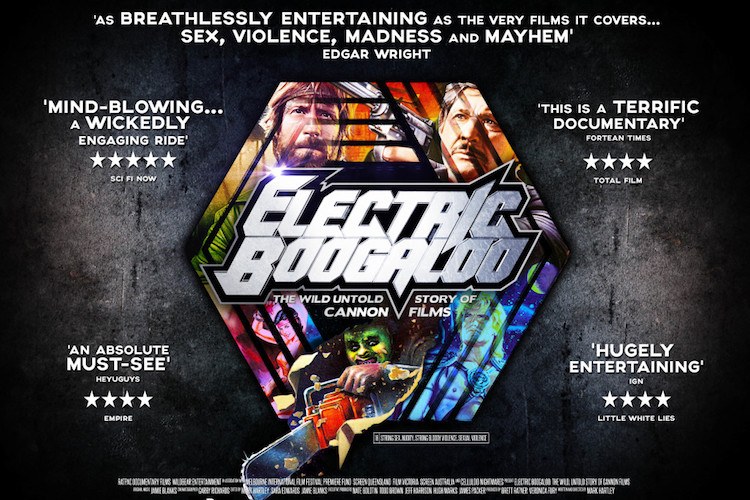

When an Israeli pilot refused to take off for another shot out of sheer exhaustion, Menahem Golan threatened him at gunpoint until the landing gear left the ground. This early anecdote sets the tone for Electric Boogaloo: The Wild, Untold Story of Cannon Films, a 2014 documentary about the company that gave us the misguided nostalgia that gave us Kung Fury.

Cannon Films was a shoestring production house struggling to keep the lights on by dubbing Swedish softcore when Golan and his cousin, Yoram Globus, bought it in 1979. The new Cannon’s mission was as pure in heart as it was clumsy in execution: to make its mark on American cinema. Electric Boogaloo proves it did, in the same way McDonald’s made its mark on American cuisine: more by brute force and over-saturation than any standard of quality. At Cannon, Golan and Globus turned ninjas into a no-budget phenomenon with Enter the Ninja (1981), starring Italian national treasure Franco Nero as the White Shinobi from Texas with a dubbed American accent not from Texas. They wove the low-grade legend of Chuck Norris as an unstoppable force of bearded violence against dirty cops and foreigners alike that provided an entire cottage industry of jokes for your little brother’s friends. They made Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo (1984) and didn’t understand what it meant then, either.

The Neon-Schlock version of the 1980s best remembered by people who never saw the real thing owes more than a little to the finance-first, art-maybe-second output of Cannon Films. And the documentary is a ludicrous, entertaining record of a company too lackadaisical to exist. Except it did. The production slate was determined by which poster (usually painted from nothing more than a synopsis and Charles Bronson’s name) pre-sold to exhibitors, who didn’t know their money would be making the movie they just paid for the privilege to screen. Cannon was a seat-of-the-pants company that made everything an inch away from logic and well outside the bounds of good taste. The atmosphere is defined best by Alex Winters, who played an allegedly Puerto Rican gang member named Hermosa in Death Wish 3 (1985) years before he stepped into a San Dimas phone booth as Bill S. Preston, Esq.

“Cannon was this weird bubble and everybody in it had this sort of wink and a nod: ‘We do love the movies… but we want to make money and we don’t care about your work conditions or the quality of the product.’”

A shrewd diagnosis based solely on his experience with the filmmaker/sadist he dubs “the perfect Cannon director” — Michael Winner. In side-burned clips of old talk shows, Winner disarms like the British answer to Mr. Rogers, even as he defends the gleeful violence and leering rape scenes present in almost every movie he ever made. On the manufactured slum sets of Death Wish 3, he wonders why a “nice, charming chap” like him is always asked to do the dirty work, despite constantly wearing the schoolyard smirk of a kid with a magnifying glass, an anthill, and no adult supervision. Marina Sirtis, forever known as Troi from Star Trek: The Next Generation, was his muse in the most regressive sense of the word. During her requisite rape scene in Death Wish 3, Winner made her lay naked for hours in the freezing cold while the director of photography lit the room. The DP tried to cover her up with his coat. The director exploded. On The Wicked Lady (1983), Winner’s shot at costume drama dignity, Sirtis was to duel Faye Dunaway with bullwhips. Moments before the camera rolled, Winner ran in with scissors, cut off her shirt and proceeded to sell the entire movie on the promise of a topless whip fight. His directing credit fades in over her naked breasts as she flees in humiliated defeat.

He was going to be interviewed for Electric Boogaloo before he died in 2013, which only makes the barrage of spit upon his fresh grave more startling. Everyone may die a saint, but nobody fought any tears for Michael Winner.

It’s the only moment when the documentary lets the darkness sneak in. Apart from some stray moments of breezy sexism — the failure of Ninja III: The Domination (1984), a sequel that tried to mix Flashdance and The Exorcist into the formula, is blamed on its female protagonist — Winner’s abuse is the only loose cog in the Cannon machine.

And then I watched Electric Boogaloo: The Wild, Untold Story of Cannon Films in 2018, the year after Me Too.

It plays a little differently now, starting with the production company logo of RatPac Entertainment, co-owned by filmmaker and six-time-accused sexual predator Brett Ratner. In an interview about Electric Boogaloo, which he co-produced, Ratner credits Golan and Globus as “mavericks” with “a love and admiration for movies.” The same mavericks who stole Bo Derek’s personal, semi-nude photos out of her luggage to use for an ad campaign. Whose love and admiration for movies motivated them to shoot un-simulated sex for The Happy Hooker Goes Hollywood (1980) without bothering to tell the lead, two-time Bond woman Martine Beswick, who only found out when porn stars walked onto the set and did what came naturally.

Michael Winner is still the agreed-upon boogeyman of the doc, but even the laziest amount of digging reveals the universal disdain for him as a soft-shoe eulogy. Last year three actresses came forward with almost identical accounts of Winner demanding they undress during auditions in the 1980s, at the height of his Cannon heyday. While introducing a screening of Death Wish 3, Alex Winter recounted Winner’s openly accepted process for shooting his trademark rapes: locked in a room with only the actress and actor(s), no crew, for three days, even if the sequence lasted no longer than 15-seconds.

But Winner’s epitaph is, at best, “Bad Guy Gets Worse.” His seedy underbelly was on display in theaters everywhere long before Golan and Globus started writing his checks. Gary Goddard, however, comes and goes through Electric Boogaloo like any other bemused passerby or shorted patron of the Cannon circus. Masters of the Universe, the live-action adaptation of the toy line, kids’ show, and marketing trick, became one of Cannon’s three bet-the-farm gambles in 1987, along with the Stallone arm-wrestlin’, truck-drivin’, son-reconnectin’ epic Over the Top and the budget-crippled Superman IV: The Quest For Peace. Each was a $20-million-plus shot at blockbusting legitimacy from a company that could only be convinced to give director Barbet Schroeder enough money to finish the $3-million Barfly (also 1987) when he threatened himself with a chainsaw. It still made cockeyed sense to entrust Masters of the Universe to first-time director Goddard; he was known at the time primarily for designing state-of-the-art theme-park entertainment. He was not known at the time, however, for sexually abusing underage boys in the guise of mentorship. To date, eight men have come forward with allegations against him from their time spent in his acting troupe during the 1970s. That’s obviously before his work with Cannon and well before Electric Boogaloo, but he’s fielded accusations of misconduct taking place as recently as 2003. Nothing has been alleged about his time on Masters of the Universe, but the documentary handily paints that a false solace.

If The Wild, Untold Story of Cannon Films makes anything clear, it’s that nothing ever mattered but movies. The rest — pay, privacy, well-being — just got in the way. It’s sculpted by the same romance that turns tyrants into auteurs. Menahem Golan pulling a submachine gun on an Air Force pilot to get a shot that wouldn’t make or break The Delta Force (1986) — a work of art so profound it premiered in a parking garage — is presented as just another kooky example of his remarkable passion for filmmaking. Same with the time he put his infant child in a horse-drawn wagon, completely unsecured, to be dragged off at full gallop. In the same interview where he referred to Golan and Globus as “mavericks,” Brett Ratner deemed Electric Boogaloo a “cautionary tale.” It may be, but not the kind anyone intended.

Cannon imploded because Golan and Globus betrayed the low-budget, assembly-line model that made it, however briefly, a genuine force in film. In tragic split-screen, Menahem talks the recklessness of $30 million budgets while footage from Over the Top, made a few years later, plays over its price tag: $25 million. Their eyes were bigger than their stomach, and their wallet was smaller yet.

“They were the forerunners of the Weinsteins. The difference is, the Weinsteins cared about quality.” Frank Yablans, the former head of MGM/UA who partnered the studio with Cannon until their steady stream of junk made him reconsider, provides the most accidentally prescient quote of all. Besides occasionally footing the bill on projects from name filmmakers who couldn’t get a meeting anywhere else, like Tobe Hooper or John Cassavetes, Cannon lived and died by its trash. It also lived and died in an environment of exploitative negligence written off as free-spirited passion. No accusations were ever leveled against Golan or Globus besides frequently shouted variations of “cheap bastards.” But the culture fostered by Cannon, celebrated by Electric Boogaloo, is how “Bad Guys Get Worse.” Too many cracks and nobody bothering to clean them. A separation of artist from art so complete it’s irresponsible — the company kept Michael Winner around exactly as long as his movies made money. The dangerous, noxious benchmark of Wanting It. The Cannon name was founded on Wanting It, wanting to make it in Hollywood. Filmmakers and actors alike had to prove they Wanted It just as bad to even get a foot in the door, and if they stopped Wanting It, there’d be someone else waiting who Wanted It more.

So goes the Rad™ legacy of Cannon Films. The name might have been recently revived, but Cannon as the 1980s knew it is dead. Its spirit lives on, though. Alongside the closing credits of Electric Boogaloo, company refugees talk with brighter eyes about the production companies they opened in its wake, supposedly wiser from the Cannon experience. One of those companies is Nu Image, producers of The Expendables franchise, whose co-founder, Avi Lerner, recently threatened Terry Crews to shut up about the whole sexual assault thing if he ever wants to share a poster with Sylvester Stallone again.