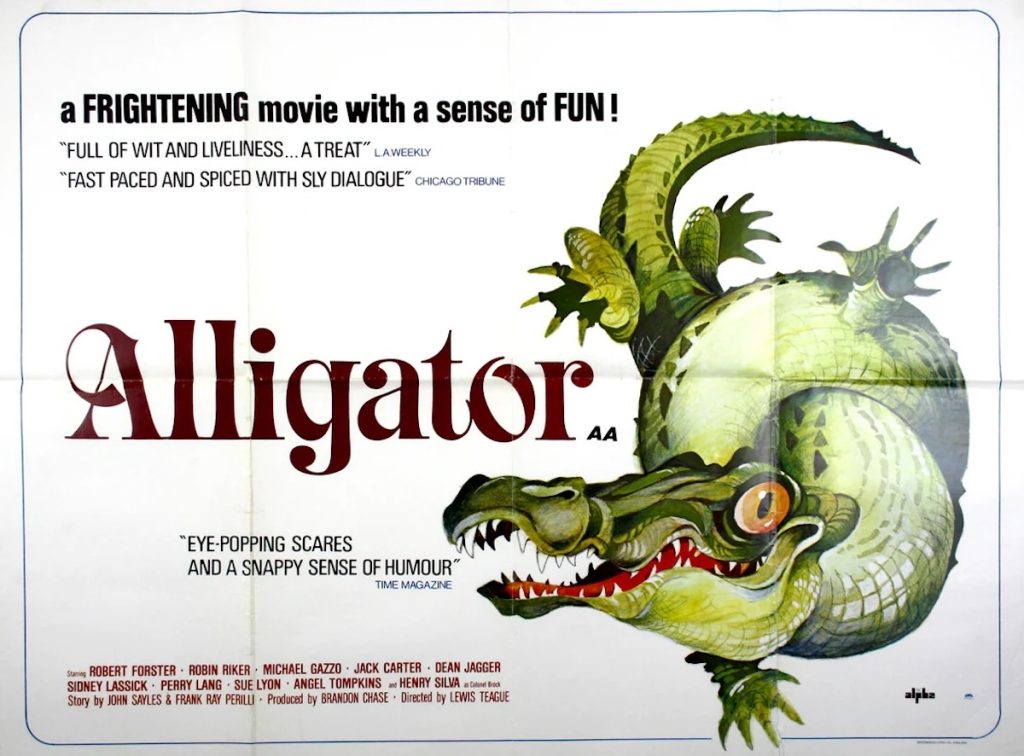

No one’s shedding a tear for Walk the Line on its twentieth anniversary. James Mangold’s 2005 biopic about mid-20th century country music stars Johnny and June Carter Cash was a hit with critics and audiences alike, grossing $188 million worldwide against its $28 million budget and netting Reese Witherspoon the Best Actress Oscar. But even just two years after its release, any conversation about its legacy had to make at least passing mention to another movie that shaped its enduring memory: Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story.

Spoofs are, of course, an enduring feature of the cinematic landscape. Some, like 1980’s Airplane!, manage to secure a greater foothold than the disaster movies like Airport that they lampoon. Others, like the Austin Powers series, helped shift the James Bond franchise in a self-serious direction that excised a lot of their previously hallmark cartoonish misogyny.

But it’s rarer to find a film like Walk Hard that so directly aims at a single movie, not just a genre. Jake Kasdan and Judd Apatow’s script functions like a heat-seeking missile for all the prestige biopic’s most recognizable tropes. It’s a diss track in cinematic form that dismantles the script so thoroughly that it might as well be a beat-for-beat remake. Catch any newly released cradle-to-grave hagiography indulging any familiar clichés, and you’ll be sure to find someone yelling the refrain of Dewey’s father in a direct shot at Walk the Line: “WRONG KID DIED!”

Anyone who’s spent even a day in a college seminar about genre studies knows at least one thing about the way they progress over time: they’re cyclical. Walk the Line, hot on the heels of 2004’s similarly acclaimed Ray, now appears to be part of the classical stage of the influx of musician portraits. By this point in the genre’s development, viewers are familiar enough with the traits to recognize their repeatability. In this case, it’s elements like the cradle-to-grave story arc, the initial spark of musical genius, the slippery interplay between life and art, the rise to fame and fall from grace, and often some final act of redemption that secures their legacy.

The parodic stage is also part of a genre’s lifecycle, but it usually comes at a point in an audience’s relationship to those conventions that has begun to shift. What makes Walk Hard so uniquely damaging to the enduring cultural memory of Walk the Line is that it arrived in theaters hot on the heels of the classical stage, when people were still enthralled rather than enraged by the formula. It’s a work of media criticism that did not wait to gain any critical distance from the work it’s deconstructing.

Walk Hard pre-empted the revisionist stage of the musician biopics, which are themselves a more muted reaction against the classically recognized canonical works of the genre. If that parody was not so directly commenting on Walk the Line, it’d make a lot of sense to pop up on the big screen now as a response to self-serious works like A Complete Unknown and Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere. The structure of both these films, which spotlight a single illustrative period in an artist’s life rather than a wider time horizon, provides a tacit acknowledgment that audiences need some tweaking to the genre before becoming entirely disenchanted with it.

At a time when it’s all but impossible to get truly original movies for adults made by studios, musician biopics have become something like intellectual property in their own right – just for people who grew up poring over the pages of Rolling Stone rather than a comic book. If Walk Hard had not short-circuited the traditional genre cycle, it’d be about time to clear the deck and restart the genre from its primitive stage again. Which would be great for many reasons, and highly among them would be the recognition of Walk the Line as the glistening jewel of the classical musician biopic.

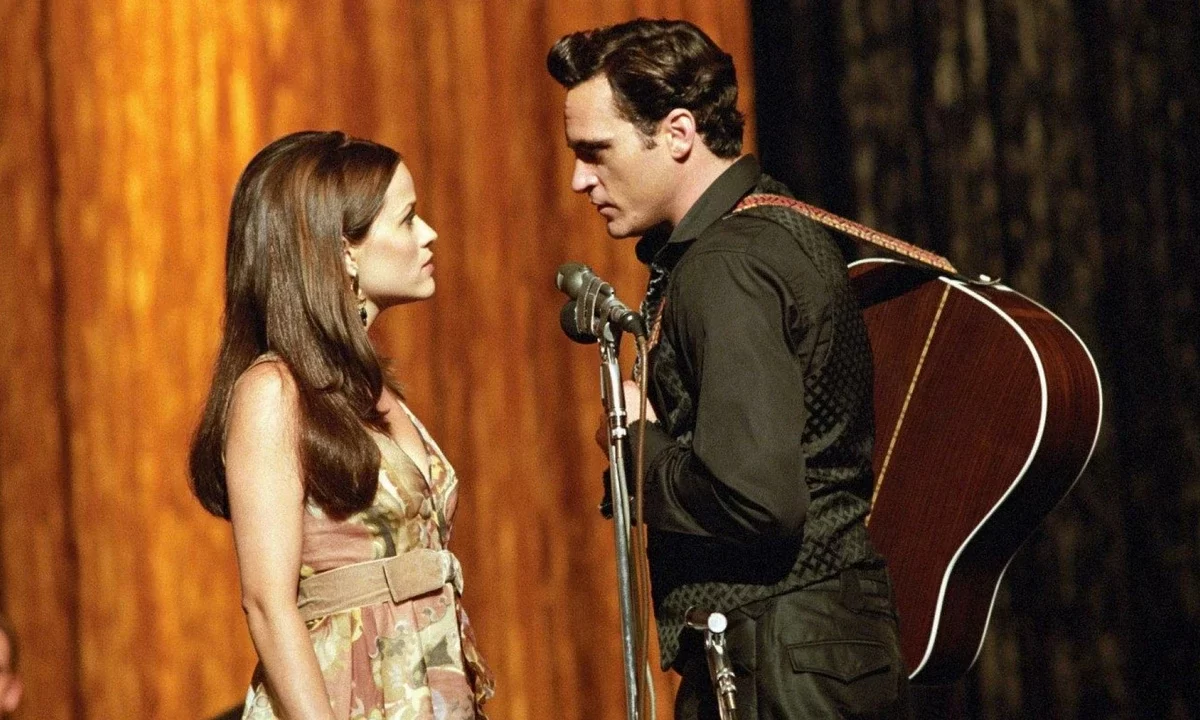

Granting Mangold’s film such status does not mean ignoring the many elements that made it so ripe for mockery. The sequence where Johnny Cash warbles the titular tune, which draws a straight line from June Carter telling him “you can’t walk no line” into the song’s conception and performance, is only missing an arrow going up the Billboard charts to hit every trope for such a montage. But the enduring power of Walk the Line proves that clichés can still hold value when executed with a sincerity that matches a work’s subject.

While Walk the Line works through a significant chunk of the Carter-Cash songbook, it’s not a jukebox musical in the mold of Bohemian Rhapsody, which just plays the hits to flatter adoring fans outside the film. It’s a musical in the truer sense of the genre, where the act of interpreting the songs is just as important as their lyrics or legacy. Joaquin Phoenix and Reese Witherspoon express the tensions flaring in their characters’ lives through their performances. That’s undoubtedly aided by the decision to record their own vocals rather than trying to merely mimic the tracks as recorded by their real-life counterparts.

The two leads of Walk the Line deliver something truly iterative with their takes on Johnny and June, not just merely imitative as most others in the genre do (often to Oscar-winning effect). There’s a desire to understand these people as more than their Wikipedia pages and let their humanity outshine the hagiography. Any time Joaquin Phoenix commands the screen, it unleashes a maelstrom of internal torment. But something still stands out in his portrayal of Johnny Cash, a relatively early stunner in his formidable body of work. Before I’m Still Here turned every Phoenix performance into an abstracted work of meta-commentary, Walk the Line found him wrangling that same life force into an achingly sincere portrait of someone who outran his many demons.

But just as the Academy voters declared, it’s Witherspoon who takes home best in show from Walk the Line. In a career that has no shortage of iconic roles, June Carter is the one who demonstrates her widest range and the deepest understanding of how time and place shape a person. Witherspoon is our premier interpreter of Southern femininity, with a bone-deep understanding of how women in a predominantly macho culture cultivate their own sense of strength and solidarity.

When June faces a disapproving remark about her divorce from a stranger, there’s a world of information about her nestled in the simple concession Witherspoon utters back: “I’m sorry I let you down, ma’am.” Beneath this acquiescence to politeness is a woman screaming inside, both at the comment itself and the fact that rage is not a tool available for her public expression. Fans of the movie have been in a similar position since 2007, when Walk Hard delivered such a brutal assessment of Walk the Line’s worth. Perhaps it’s time those fans take the opposite tack of June in the scene.

“Walk the Line” is available for digital rental or purchase, as is “Walk Hard.”