One of the most anticipated films in competition at this year’s Cannes Film Festival was Sofia Coppola’s The Beguiled. The Civil War period piece — which centers on the drama caused by the appearance of a wounded Union soldier at a secluded girls’ school deep in Confederate territory — was met with overwhelmingly positive reviews, which isn’t surprising, considering the pedigree behind and in front of the camera. (The film stars Coppola-regular Kirsten Dunst, as well as Colin Farrell, Nicole Kidman and Elle Fanning.) What is surprising is the film’s origins: It is a remake.

It is also a specific kind of remake, one that, for as prevalent as remakes are in today’s cinematic landscape, is exceptionally rare: It is a remake of an art-house film, made anew for an art-house audience. Such remakes differ from the standard examples because they are not simply attempts to cash in on previously established brand awareness or basic nostalgia; nor are they English-language versions of foreign films; nor are they new adaptations of the original source material. These remakes are something else entirely, often highly personal to the filmmaker, often stemming from the sense of a challenge.

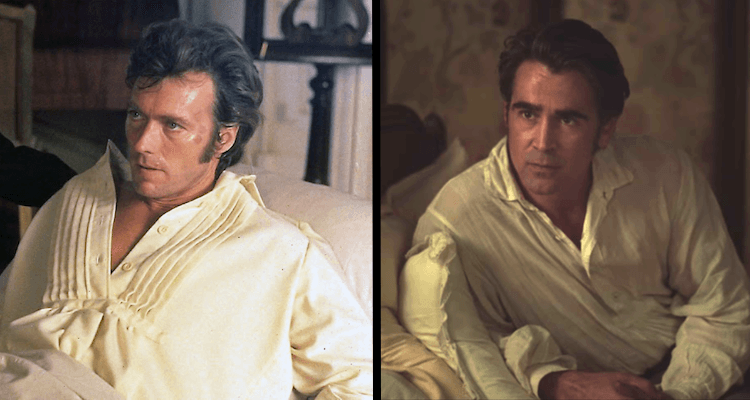

For her part, Coppola has found the perfect vehicle in which to enter this small sub-genre. The original The Beguiled (1971) is a mostly forgotten film, despite the high profile of its makers: It was the fourth collaboration between director Don Siegel and star/producer Clint Eastwood. If a film from the team that also brought the world Dirty Harry seems like an odd fit to be reinterpreted as a modern-day treatise on gender power dynamics from one of Hollywood’s leading female directors, that’s because the original was an odd fit to begin with.

That the story of The Beguiled is so rich with further possibility in its exploration of gender, power, privilege and sexuality makes it fertile ground for a remake (the original also sets its unsentimental sights on race, but, Coppola’s new version has excised that subplot, which seems like a cop-out). It doesn’t hurt that the original is also deeply flawed. Although it is a highly visceral film, filled with good performances (Eastwood’s included) and a twisted sense of anticipation, the narrative does feel somewhat undercooked, the ending rushed, and many of the character choices under developed, while its quotidian cinematography does no justice to its lush, gothic setting. (Siegel was never known for being a stylist, but there is nothing in the film as hauntingly shot and tensely staged as the football stadium manhunt in Dirty Harry.) These are areas where an aesthetic and tonal master like Coppola could come in and add a welcome touch.

More interesting, though, is how Coppola’s version is set to tackle the themes of the original film. While it’s reductive to call the Siegel version misogynistic (although it certainly plays well to misogynists: I found at least one gross, rambling modern review of it, on an MRA site that will go unnamed, which called it an “in-your-face, red-pill masterpiece”), it is a film about women from a man’s point of view. A man of his era, at that: Siegel himself broke his film down pretty succinctly, saying it was about “the basic desire of women to castrate men.”

Coppola has openly stated that her desire to remake the film (which she was introduced to only a couple of years ago to by her long-time production designer) came from her wanting to flip the story to tell it from the women’s point of view, which seemed to her entirely more natural and worthy.

This drive is what puts her in the company of the aforementioned rare breed of art-house directors, remaking art-house films, for an art-house audience, for reasons that are entirely personal and idiosyncratic, but which nonetheless end up being surprisingly similar.

Friedkin had said that he wanted to make an action thriller that tackled the notion of existential dread (in which the nation was steeped during the late ’70s), and that Clouzot’s film provided the perfect spine on which to graft his obsessions. By doing so, in a manner similar to what Herzog did with Nosferatu, Friedkin engaged with the original film in a way that other remakes hardly ever attempt to.

In those cases it helped that the original films — Nosferatu and The Wages of Fear — prove extremely malleable to the concerns of different time periods (which is also why it should come as no surprise that both are slated to be remade by current art-house darlings, the former by The Witch director Robert Eggers, and the latter by gonzo journeyman Ben Wheatley).

Yet along came Soderbergh, who had made a career of traversing between the art house and the megaplex, to give it his best shot, bringing with him A-lister George Clooney, with whom he had recently collaborated, to great commercial success, on another remake in the star-studded Ocean’s Eleven. Alas, that success was not to be replicated with Solaris, despite the fact that Soderbergh’s version is shorter than Tarkovsky’s by over an hour and is significantly easier to follow.

Despite these changes, Soderbergh’s version failed to connect with audiences who were expecting a big-budget space thriller with George Clooney (to this day, I don’t think I have ever witnessed as many walkouts as I did for the opening-weekend screening of Solaris that I attended). A quiet, intimate, deeply personal meditation on loss and memory, it doesn’t seem right to say that Soderbergh’s Solaris is better than Tarkovsky’s, being that they are so different from one another (neither of them, according to a consensus among readers of the novel, are particularly faithful to Lem’s story), but it does explore avenues that the previous version did not. Soderbergh has said that this was the reason he decided to take on the project in the first place: He thought there was enough material for several films, and thought that his film would serve as an interesting companion piece to Tarkovsky’s.

Herein lies the thread that connects all of these examples: They are not merely the case of a director wanting to take ownership of the original by reshaping the material to suit their style or obsessions, but rather, it is them wanting to take on a specific challenge that they felt called to when watching the original films. These remakes are meant to be viewed alongside the originals, rather than in place of them.

Whatever public reception Sofia Coppola’s new version of The Beguiled meets once it has its proper release is yet to be seen, but if it’s anything like these other examples, it’s probably too much to expect it to find much in the way of crossover success. However, by being part of this strange subsection of art-house remakes, it ensures that it will be remembered as, if nothing else, a prime example of cinema in conversation with itself.

Zach Vasquez lives in Los Angeles, an indie town that never got mainstream popularity.