On page 89 of Abel Ferrara’s new memoir Scene, the director provides an enthusiastically detailed description of how to make crack cocaine. By the end of the paragraph he’s pleading with the reader: “Don’t try it. Rip this recipe out of the book and burn it. You have to be Dante to describe where one hit leads you.” Ferrara says he only had a serious crack habit for a couple of years in the early ‘90s – his most artistically accomplished period, oddly – but was able to wean himself off the stuff by getting into smack and becoming a junkie instead. A dealer friend told him heroin was okay just so long as he didn’t do it three days in a row. “Better advice was never given, but it was given to the wrong guy because skipping days is not my MO.”

He didn’t do it three days in a row. Ferrara snorted smack for 14 years straight.

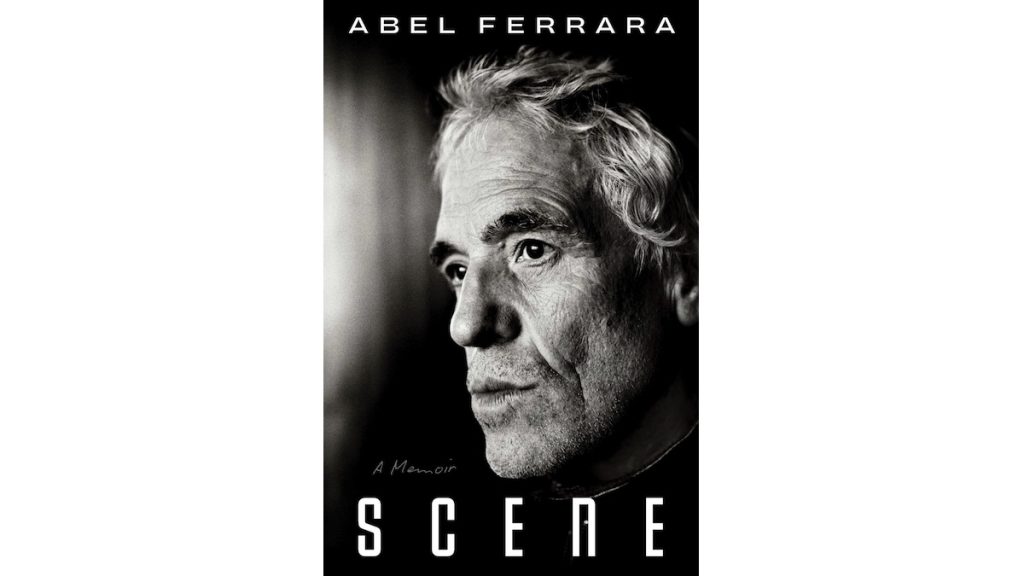

Revelations like this are pretty much everything one could have hoped for from a memoir by the picaresque gutter poet, who has spent the past four decades playing Virgil to adventurous moviegoers, taking us on tours of grimy underworlds full of sleaze, desperation and spiritual torment. That he’s somehow alive, sober, and still making films at the age of 73 is a shock to everyone, especially himself. Scene is partially a chronicle, something of an amends and it reads like a late night rant. You didn’t expect an Abel Ferrara autobiography to be linear, did you?

A lot of the time it feels like the book is shouting at you. If you’ve ever heard an interview with Ferrara, bellowing abundant obscenities in his raspy Bronx roar, you know the voice. He writes like he’s jabbing a finger in your chest while he’s telling you a story. The book rambles and skips around in time, alternating anecdotes about his father — an alcoholic and compulsive gambler who killed himself in 1980 — with tales of shady characters like his Uncle Bobo, who used to bring underage girls to Jake LaMotta’s nightclub, and the frightening Fun City moneymen who financed the fledgling filmmaker when he was making porno flicks fresh out of SUNY Purchase.

Ferrara’s career trajectory – from pornography to grindhouse exploitation to arthouse darling – is fairly unprecedented. But then, there’s really nobody else like Abel Ferrara, a natural born hustler with a carny barker’s knack for titillation that’s simultaneously suffused with an intense spiritual longing. His 1992 masterpiece Bad Lieutenant is somehow both the most blasphemous and the most devoutly religious movie I’ve ever seen – a sordid Stations of the Cross culminating with a full-on Last Supper in a crackhouse and Harvey Keitel taking the Gethsemane sequence to heights of anguish seldom seen in American cinema. Of his star, the filmmaker says, “Harvey knew how to put the spurs to the demons we were all riding and exorcise them in front of the camera.”

Making the movie spooked him. “I walked out of the sunlight into that big dark church with ‘Fuck’ scrawled across the altar and I thought, we shouldn’t be doing this.” A recovering Catholic into Buddhism and meditation these days, Ferrara confesses to “still looking over my shoulder for a nun with her pointer stick.” But the book is otherwise surprisingly cagey about matters of faith, given how many pictures he’s made on the subject. His penchant for digression can be frustrating, with the memoir veering off in occasionally confusing flurries of dealers, lovers and unhappy endings. The chapter about his affair with Asia Argento is chaotic enough to be an Abel Ferrara film of its own, and it’s impossible not to be moved by his remembrances of Chris Penn. But the conversational tone makes a reader wish you could every once in a while interrupt him for clarification: “Wait, did you just say you were dating Debbie Harry at the time?”

There are a lot more pages than you might have guessed devoted to Body Snatchers, the 1993 sequel-slash-remake that represented Ferrara and his regular crew’s lone attempt to work inside the Hollywood system with a major studio. There are also tantalizing details of another that almost happened. Obsessed with King of New York, Al Pacino originally wanted Ferrara to direct Carlito’s Way, and the project looked for a bit like it might be moving forward with Keitel in the lawyer role eventually played by Sean Penn. It all blew up over a page-one rewrite by the studio’s preferred screenwriter David Koepp (“a fucking travesty,” according to Ferrara) and an incident at Cannes when the director grabbed a bottle of white wine off the table of Universal Studios chief Tom Pollock to bring with him for the cab ride back to the hotel, tucking it into his suit jacket as he walked away.

“What is wrong with me? A self-destructive nature? An innate feeling of unworthiness? A mistrust of success? What’s wrong with me is that I’m an alcoholic,” Ferrara concludes. In its rambling, roundabout way, the book builds to the filmmaker finally getting sober, finding a new life in Rome and a renewed passion for his art. But Scene is not a drag in the way a lot of similar recovery stories are. He’s not lecturing, and the rare times the author gives advice – like ripping out the page with the crack recipe and burning it – feel hard-earned and true. He sounds grateful to still be here. And a little amazed. Ferrara compares himself and other filmmakers to the ancient cave-painters “scratching pictures into stone to confirm it, as proof we exist. Proof we care about sharing what we learned with another human being.”

“Scene” is on bookshelves now.