Eighty years ago this June, cinema went aquatic with the debut of swimming actress Esther Williams. Though technically debuting on-screen in the 1942 feature Andy Hardy’s Double Life, the 13th feature in the long-running series starring Mickey Rooney as the title character, it wasn’t until the 1944 feature Bathing Beauty that Williams was actually presented to audiences as someone who could act, sing, and swim.

It isn’t nearly as jarring today to envision an athlete making a bid for movie stardom; whether they’re successful at it is another story. To watch an Esther Williams movie is to see not only the makings of a star, but how Williams leveraged that stardom to illustrate her athleticism. And with the 8t0h anniversary of Bathing Beauty and the 75th anniversary of her work in Neptune’s Daughter, it’s high time we start appreciating Williams for the actress, athlete, and entrepreneur she was.

Williams was initially discovered to be a derivative of another star: MGM wanted a star to rival ice skater Sonja Henie, who had made Fox a lot of money. But where Henie wasn’t the best actress – some of her acting is downright abysmal – the goal was to craft both a star and athlete. Thus, MGM head Louis B. Mayer forced Williams to go through nine months of acting, diction, and vocal training, so that when she finally showed up on-screen no one could accuse her of being a total amateur.

Bathing Beauty is not one of Williams’ best features but it is important, as it presented her as a leading lady opposite Red Skelton, whom Williams would be paired with in three additional films. Williams plays Caroline Brooks, a college swimming instructor planning to give up her career for marriage, only to have it all go kaput due to a series of comic hijinks. Thus, Skelton ends up spending the majority of the runtime trying to win her back, as he usually did in these movies.

Williams regularly played a swimming teacher or someone with a connection to a swimming attraction. It’s amazing how many connections to the water Hollywood screenwriters could make. The 1952 feature saw her play the first woman to cross the English Channel, Annette Kellerman, in Million Dollar Mermaid; in 1956’s Easy to Love she literally plays a version of herself, a woman paired with another swimming star who performs shows at the real-life theme park Cypress Gardens, mimicking Williams’s own Aquacade show with a pre-Tarzan Johnny Weissmuller. Even Williams herself said, “I always felt that if I made a movie, it would be one movie; I didn’t see how they could make 26 swimming movies.”

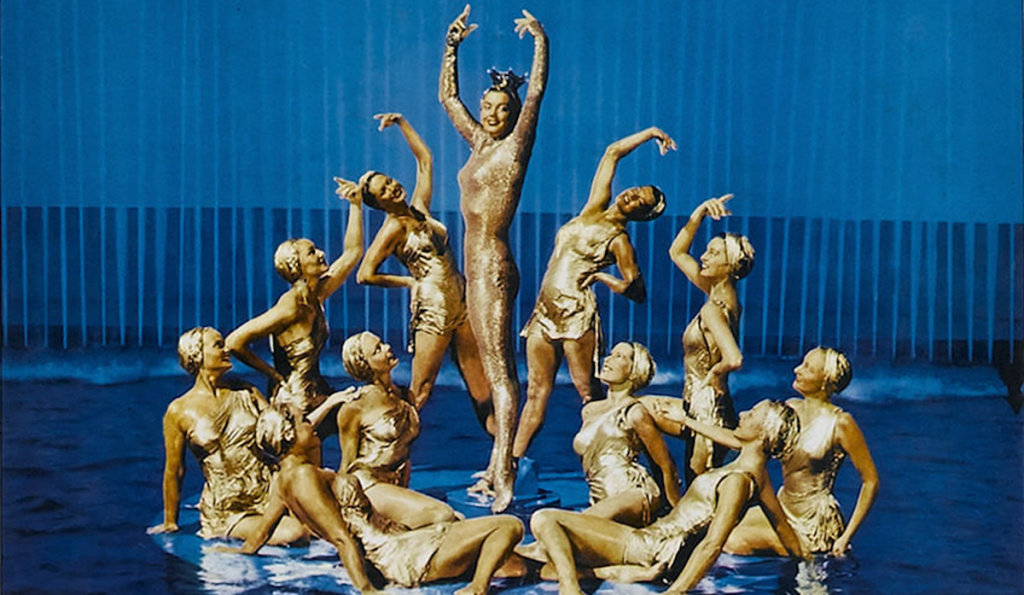

But watching a typical Williams vehicle, the audience is enthralled less by the stories – which were often focused on various romantic triangles or rectangles – than the sheer spectacle and prowess of her big swimming finales. Remember, Williams was meant to be a better version of Sonja Henie. Where Henie could certainly spin circles around everyone on the ice, Williams’s aquatic feats on-screen are powerful, aggressive and, in some cases, death-defying.

Wililams did the work not only of a star but of that star’s stunt double, and has the stories to prove it. But none of them compare to her work in 1952’s Million Dollar Mermaid. She’s said to have ruptured an eardrum due to her numerous takes underwater; the numerous eardrum ruptures tended to make her disoriented while up on high diving boards. On top of that, the stunt for Mermaid involved a high dive while wearing a heavy headdress. According to her autobiography, her neck popped as soon as she hit the water and when she swam to the surface her upper body was paralyzed. An x-ray revealed she had broken three vertebrae. Williams wrote, “I’d come as close to snapping my spinal cord and becoming a paraplegic as you could without actually succeeding.” It’s amazing to watch the finished stunt on-screen because Williams continues to do everything with a smile on her face.

Williams’s work is a testament to both her skills as a performer and an athlete. She can just as easily play a love scene as dive from a 60-foot platform. Hell, sometimes she can play the love scene while teaching someone to swim, as is the case in the 1948 romantic drama On an Island With You, wherein she and Ricardo Montalban performa a romantic pas de deux while swimming parallel to each other; she writes in her autobiography that leading man Van Johnson wasn’t able to swim when they worked together.

Williams knew she was a novelty and she wasn’t content to fade into obscurity. She ended up selling swimming pools and crafting her own long-running bathing suit line. In a way, her transition out of the movies holds a lot in common with performers today. But what I still love about Williams’s movies is just watching her strength. She is lovely to look at, but she showed audiences that women can be beautiful and powerful. Watching her cut through the water like a knife, or dive off a high dive into a hoop, or glide on a Jet Ski through Cypress Gardens…it shows the strength of a woman to be a serious athlete. Sure, her work is gussied up amongst sequins and romance, but it delivers a powerful message nonetheless.