Comedian Flip Wilson blamed it – whatever it happened to be – on the devil. The Rolling Stones asked us to find sympathy for the man downstairs. The devil’s been around, in his various identities and guises, for thousands of years. But Hollywood really fell in love with the devil in the 1970s, when prestige studio films and low-budget, drive-in fodder alike were obsessed with Old Scratch, Beezlebub and his demonic minions.

Rosemary’s Baby came out in 1968 – a genuinely hellish year in real life, a year of assassinations and war and protests and police brutality – and the movie couldn’t have been more appropriate for its time. But the 1970s were prime time for the Devil, and his on-screen adventures in the decade range from high-budget thrillers to exploitative grind-em-out flicks.

There’s never been and never will be a better movie about the devil and demonic possession than The Exorcist, director William Friedkin’s 1973 thriller about a little Georgetown girl (Linda Blair) possessed. The making of the film, its controversies, and its critical and box-office successes don’t need recounting here.

(It’s worth noting that the demon that possessed Regan was probably not the actual devil. The entity inside Regan claims to be the devil, and Father Karras scoffs at the idea, but that’s what I’ve always rolled with: The demon, legendarily Pazuzu, is the devil or close enough for jazz, their intentions and tactics sufficiently dire that Father Merrin decides the details don’t matter.)

Honestly, I’m not quite sure how I got into the theater to see The Exorcist; I was too young, by a couple of years, to get into an R-rated movie. But my friends and I all saw it. There had been weeks of anticipation among us, and in the run-up to seeing it, one friend seemed to think the Exorcist himself was the cause of the spooky goings on in the film. “It’s the Exorcist!” he would shout when a thunderstorm raged outside our school and rattled the downspouts of the 100-year-old building.

I was low-key beside myself with eager anticipation, reading articles in Time and other magazines that recounted how early audiences had reacted to the film: with hysteria, fainting and vomiting. When we went, two women in the row directly behind me in the packed theater kept talking about how anxious they were and that they were afraid they were going to be sick. I was literally on the edge of my seat during most of the movie, in part because of the unsettling artistry of Friedkin’s film, and in part because I was afraid the women would upchuck on me.

Two lesser sequels followed in the years to come, with reboots and sequels and the like continuing to spin off clear through The Exorcist: Believer, set for release in October 2023. At least one more sequel is planned after that. But some of the quick-and-dirty efforts to capitalize on the success of The Exorcist are much more interesting than the official sequels and remakes.

The 1970s was a time when a movie could do huge business at the box office and, within seemingly months, low-budget imitators – sometimes retitled import films with a canny marketing campaign – appeared at theaters and drive-ins, happy to catch a little ticket sales spillover.

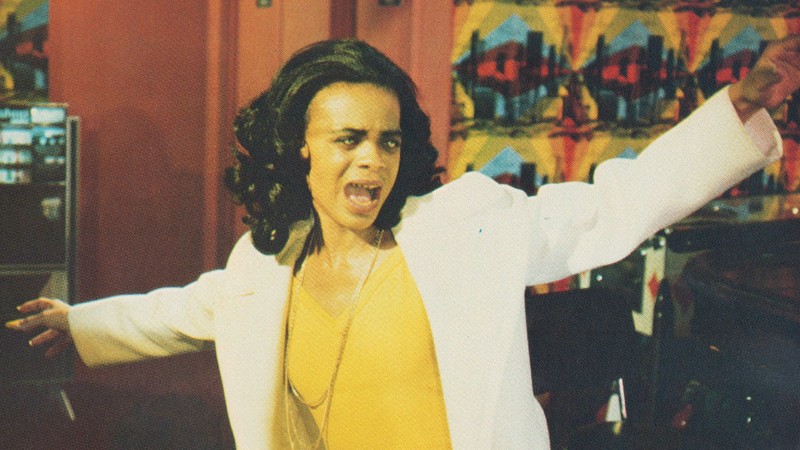

Abby, a blacksploitation take on The Exorcist released by American International Pictures in 1974 and directed by expert exploitation director William Girdler, drew a lawsuit from Warner Bros, which had released Friedkin’s film. Girdler was unapologetic that Abby was perceived as a rip-off. “I got more on the screen for the money spent on Abby than Billy Friedkin got on the screen for the money spent on The Exorcist,” Girdler told the Courier-Journal in Louisville.

Beyond the Door was an Exorcist imitator with Italian origins, completed in 1974 and released in the United States in 1975. It was nightmare-inducing for women in its potential audience: the main character, played by actress Juliet Mills, becomes possessed while pregnant. Beyond the Door was likewise sued by Warner Bros.

But by the time Exorcist imitators began to slowly decline in number, moviegoing audiences had already found their new devilish tormentor. To me at least, it seems clear that the source of deviltry in The Omen is not the devil himself, but who but the devil could be behind the plans of global domination of the Antichrist? The figure, long prophesied as the evil counterpart to Christ, got the starring role in The Omen, released in 1976 and directed by Richard Donner (like Friedkin a Hollywood pro) and released by a big studio (in this case 20th Century Fox).

Again, this is a familiar story, so just a brief note: Damien is the son of the U.S. Ambassador to England (Gregory Peck) and his wife (Lee Remick). But five-year-old Damien isn’t their child, and his origins are quite bizarre. A priest played by Patrick Troughton and a photographer played by David Warner investigate, try to persuade the ambassador, and meet grisly ends.

The Omen plays a bit like a murder mystery, with suspects – and in some cases guilty parties – played by the likes of crazy nanny Billie Whitelaw. Like The Exorcist, The Omen was a hit with moviegoers, made the Antichrist and the sign of 666 touchstones of the cultural conversation, and inspired sequels in which creepy little Damien grows up – by the third installment – into Antichrist Sam Neill. The original was remade in 2006.

With the Antichrist dominating theaters, it was up to the drive-ins to bring the devil back to moviegoers. There’s something wonderful about a premise as broad as “The devil and his minions get into hijinks” that allows for a movie treatment like Race with the Devil. Released in 1975, the film is like The Fast and the Devil-Curious, turning the devil story into a Cannonball Run-style stunt movie.

Race with the Devil brings together the best of three worlds: Motorcycle racing, RVing and small-town devil cults. Two couples – played by Peter Fonda, Warren Oates, Loretta Swit and Lara Parker – think they’re going to have a relaxing vacation in the backwoods, but they see devil worshippers conducting a human sacrifice and the titular race begins. If you think small towns are scary, wait until you see how alarming highway mayhem with an RV and various trucks and old station wagons can be. Also in 1975, The Devil’s Rain took satanic movies into new territory: What if Ernest Borgnine were the ringleader of a small-town devil cult? And what if you turned out a drive-in staple that featured Eddie Albert, Tom Skerritt, Keenan Wynn, William Shatner and Anton LaVey, the actual founder of the Church of Satan in the United States?

So what was the cause of this particular subgenre – and why did these pictures prove so popular? No less an authority on horror fiction and movies than Stephen King celebrated and explained the appeal of The Exorcist in Danse Macabre, his 1983 book that mixed autobiography and cultural commentary.

The film is about “explosive change,” King wrote, “a finely honed focusing point for that entire youth explosion that took place in the late sixties and early seventies. It was a movie for all those parents who felt, in a kind of agony and terror, that they were losing their children and could not understand how or why it was happening.” In other words, the the 1970s, these movies helped Americans face the devils in their own lives.