“Road House is the best movie ever made. It’s got boobs and explosions!”

That above was told to me by a teenage neighbor some 23 years ago. Not the sharpest knife in the drawer—the big lug went to Texas A&M on a football scholarship but flunked out halfway through his first year—yet truer words have never been spoken. The film’s own producer, Joel Silver, once summed up the plot as “boobs and bombs.”

Certainly, the copious amounts of T&A helped make Road House a modest hit when it came out in April of 1989, and guaranteed its continued popularity on home video and as a staple of cable TV over the next several decades. So too would its reputation as one of, if not the ultimate, ‘so-bad-it’s-good’ movie. In his two-and-a-half star review, Roger Ebert wrote, “Road House exists right on the edge between the ‘good-bad movie’ and the merely bad.” It was immediately canonized within that disreputable category when it was nominated for five Golden Raspberries (including Worst Picture) at the following year’s Razzies, and has continued to be regarded as such by critics.

But here’s the thing: Road House is a much better and far more interesting film than either its hormone-crazed or irony-poisoned boosters would have you believe.

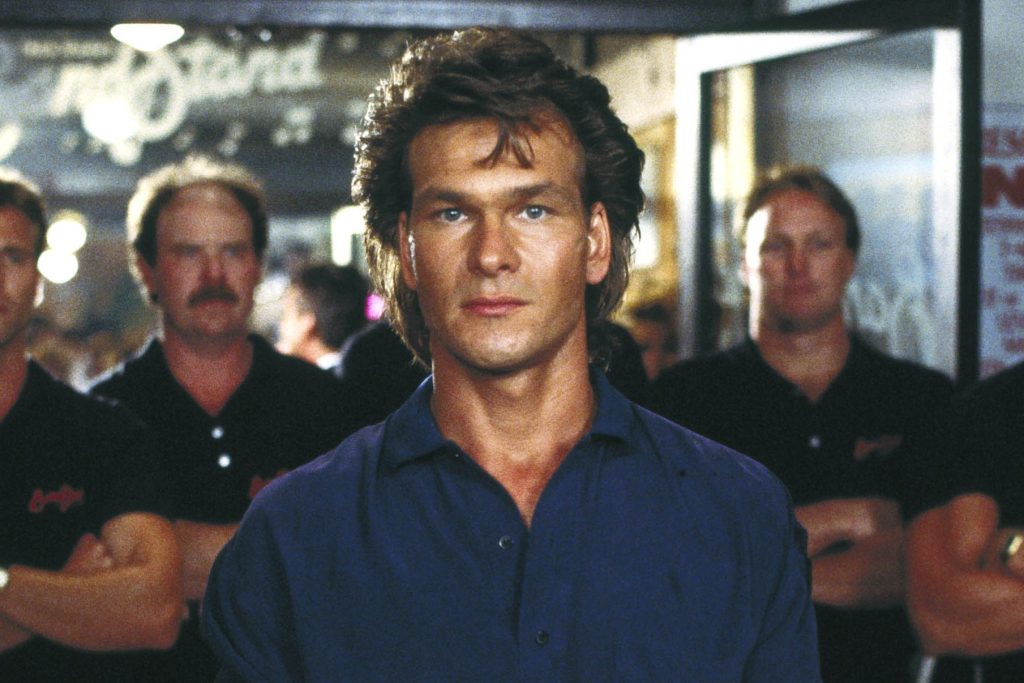

What makes Road House so interesting—and the thing that makes smarmy viewers tie themselves into knots defending their enjoyment of it—is its strangeness. The film, about a bar room bouncer (or “cooler”) named Dalton (Patrick Swayze) hired to clean up a rowdy nightclub called The Double Deuce in Jasper, Missouri, only to find himself engaged in a bloody war of attrition with corrupt town boss Brad Wesely (Ben Gazzara), sits at the nexus point of the American western and the Hong Kong chop-socky picture. But rather than load itself with obvious references to those genres, it plays things straight, and it’s that sincerity that throws viewers for a loop.

This is also true of the off-kilter world in which it’s set, one where dive bar bouncers carry the mythic status of Old West gunfighters and where Saturday Morning Cartoon-style mayhem is an everyday occurrence. Road House is not as overtly fantastical as, say, Walter Hill’s similarly two-fisted odysseys The Warriors or Streets of Fire, but it’s not far removed.

The strangeness of the plot and setting are made more noticeable by how aptly-named director Rowdy Herrington and screenwriter Hilary Henkin (credited alongside David Lee Henry, nee R. Lance Hill) subvert viewer expectations. My dumb childhood buddy and Joel Silver may have focused on the boobs and bombs, but just as prevalent, if not moreso, is the emphasis on male beauty, homoeroticism, and Zen philosophy.

Henkin, who at the time was known as “the girl who writes boy movies”, distinguishes the character of Dalton from every other action hero at the time (and since) by making him a cerebral New Agey-type: he holds a philosophy degree from NYU, he reads Jim Harrison novels on his downtime, he practices Tai Chi. He will absolutely break a guy’s kneecap or rip his throat out when he has no choice, but most of the time he tries to avoid confrontation. His work motto is “Be nice,” and, as he later tells his doctor love interest (Kelly Lynch), “Nobody ever wins a fight.”

(Anyone who’s seen Henkin’s next project, the gonzo neo-noir Romeo is Bleeding, should recognize how distinctive her voice was, and how poorer we all are that her career fell off after the controversy surrounding her work on the political satire Wag the Dog.)

Herrington, for his part, turns the camera’s lustful gaze upon the chiseled, feather-haired, and at one point, bare-assed beauty of Swayze, and then, for the film’s second-half, the rugged, silver-maned allurement of Sam Elliot’s Wade Garrett, the other greatest cooler in the land and Swayze’s mentor/big-brother figure (seriously, Elliot in Road House may be the most handsome any man has ever been on film). The relationship between Dalton and Garrett is shockingly (for the genre) tender, with just enough of an erotic undercurrent to add an undeniably queer context to the proceedings.

The addition of these unexpectedly Eastern and feminine aspects make the brutality of the violence stand out even more, including Dalton’s gruesome showdown with henchman Jimmy Reno (Marshall Teague, who gets to deliver the immortal line, “I used to fuck guys like you in prison”) or the climactic shotgun massacring of Wesley at the hands of pissed-off locals (this plot point was, according to Ebert, based on a true story and the catalyst for the entire movie). It’s this dichotomy that makes Road House such a singular work of action cinema, and the reason it has such a diverse fanbase—a large percentage of which is made up of women and queer people, as evidenced by its Letterboxd reviews or the crowd at any rep screening.

It’s also what makes the prospect of the forthcoming remake of the same name such a bad idea. It’s not merely that Road House is too unique to lend itself to a modern update, it’s that centering the new version around the world of MMA fundamentally misunderstands the spirit of the original. Herrington’s movie, with its over-the-top theatrics, comic book superheroics, and undercurrent of gayness has far more in common with professional wrestling than the boring bro culture of the UFC (nothing highlights this more than swapping out beloved wrestling icon Terry Funk for that douchebag Conor McGregor).Regardless of how the remake fairs, the OG Road House will remain its own weird, beautiful thing, a favorite comfort watch amongst its cult of fans, as well as a perpetual discovery for younger audiences. The only thing that will change as time goes on is it won’t be regarded as a classic of the good-bad variety, but appreciated for what it actually is: an outright good movie.

“Road House” is streaming on Prime Video and Max, and also has a nice 4K from Vinegar Syndrome.