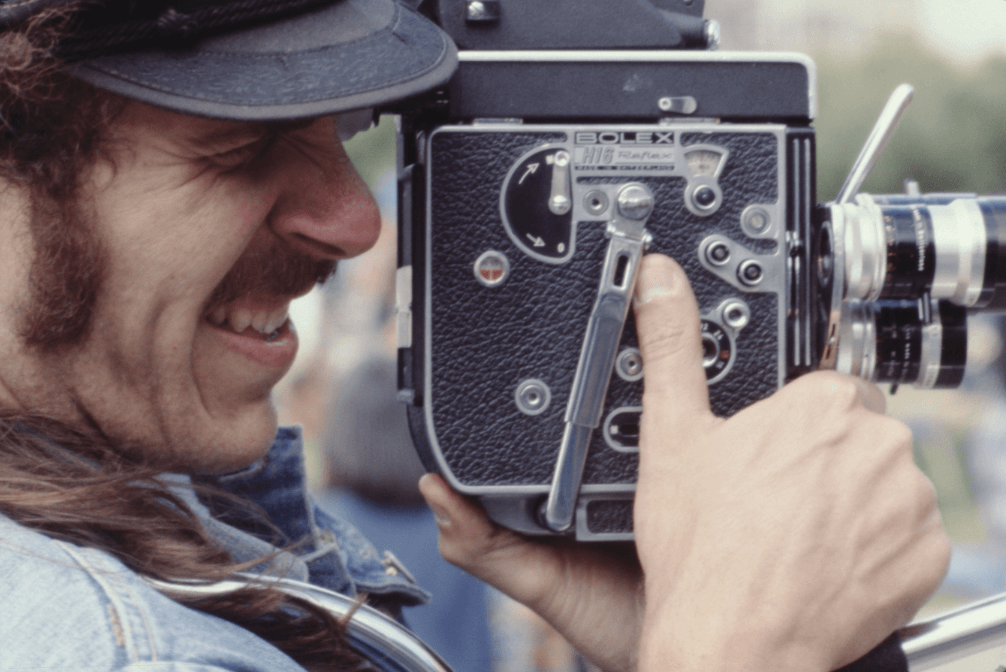

In the decade after Stonewall, gay culture exploded and thrived in ways previously unthinkable. One filmmaker who covered every facet of it – from the parades to the adult film market – was Arthur J. Bressan, Jr., who also holds the distinction of making the first dramatic feature about AIDS, 1985’s Buddies. For Bressan and others of his generation, the ’70s was a time of liberation and exploration, which he did in the X-rated features Passing Strangers and Forbidden Letters (both recently restored by Vinegar Syndrome in partnership with The Bressan Project and the Outfest UCLA Legacy Project for Moving Image Preservation) and the 1977 documentary Gay USA, which incorporated scenes shot by Bressan at San Francisco’s first Gay Freedom Day in 1972.

Bressan edited this footage into a ten-minute short called Coming Out that was a warm-up for his first feature. Released in 1974, Passing Strangers makes no bones about the audience for which it was intended, opening with a scene of hardcore penetration, which is revealed to be from one of the features at an “art cinema” where the projectionist is played by Bressan (but voiced by another actor since the entire film is dubbed, a function of its extremely tight budget). Spotting an unusual personal ad in the Berkeley Barb, he calls up his friend Tom (Robert Carnagey), who reveals it’s a quotation from Walt Whitman’s poem “To a Stranger” that he has repurposed as a message to a “PASSING STRANGER.” Little Tom knows the impact this gesture will have on the young man who responds to it.

That would be Robert (Robert Adams), a closeted 18-year-old who lives with his parents and has yet to act on his longings. In the first half of the film, which is shot in black and white, Robert and Tom exchange letters describing their daily lives and what they’re looking for. All the while, Bressan makes sure sex scenes appear at regular intervals by showing Robert hanging around a porn shop where he watches several loops (soundtracked by a lone Arp synthesizer), then going home to masturbate. Meanwhile, the curly haired and mustachioed Tom (who’s 28 and works for Ma Bell) tells of frequenting the baths and bars and cruising on Polk Street (a sequence underscored by player piano music – Jeff Olmsted’s score is nothing if not eclectic). Eschewing dialogue, Bressan edits this so it all plays out with nods and glances, demonstrating the way gay men communicate with each other without the need for talk.

The most visually striking passage comes after Tom asks Robert for a photograph and Bressan goes inside the younger man’s head to show how he sees himself (as a clown, apparently) and the sorts of sexual fantasies he has. These involve several men getting naked in his room, watching approvingly while he plays with himself, and jumping up and down while bubbles are blown from off-screen. An arty touch, to say the least, and it’s far from the film’s last.

The picture bursts into color at the halfway point with Robert and Tom’s first face-to-face encounter on a sunny day in June. For their meeting place, Tom picks Land’s End, which is secluded enough that other gay men use it for nude sunbathing. Initially, Robert and Tom engage in more innocent pursuits, exploring the terrain and flying a kite while Robert casts longing looks at his companion. Then comes the moment of truth as they tentatively kiss, after which they find a tree to spread a blanket under so they can make love.

Knowing this is Robert’s first time, Tom is patient and gentle with him, making sure the experience is as pleasurable as possible. When they take a breather, Robert imagines the two of them jumping up and down, a naïve expression of his feelings of exuberance and Bressan’s way of highlighting the joy of making a physical connection with another man. Lastly, the two of them couple in an echo of the film’s opening shot, only this time the participants aren’t faceless ciphers, but flesh-and-blood characters we’ve gotten to know a little.

By the time he made 1979’s Forbidden Letters, Bressan had a more refined technique and complex story to apply it to. (He also had direct sound for the dialogue scenes, which helps make them come off more naturalistic.) With its mix of black-and-white and color cinematography, alternation between synthesizer pieces and acoustic ballads, and the use of Land’s End and other locations from Passing Strangers, Forbidden Letters could almost be its sequel. It even has the same lead, Robert Adams, who plays Larry, the younger lover of 31-year-old Richard (Richard Locke), who’s getting paroled after 11 months in prison. (The “big day,” as it’s called, is May 27, which just so happens to be Bressan’s birthday.)

“In a way, time stopped for me when you got arrested, and I want it to start again,” Larry says in one of the letters he wrote but didn’t dare send to Richard in prison, for fear of outing him. Urged by their prostitute friend Iris (Victoria Young) to get out and enjoy the “homo heaven” that is San Francisco, Larry goes to an “art house” and fantasizes about observing the three-way in it in person (a shift signaled by the switch from the porno’s funk score to classical), then walks around the Castro and goes home with a photographer he picks up nearby.

It isn’t until 28 minutes in that Bressan gets to the letters that give the film its title. First is a sampling of Richard’s to Larry over disorienting shots of him languishing at Alcatraz, climaxing in a shot of the two of them standing back to back in adjoining cells, bringing themselves to orgasm (in a way Jean Genet would have likely approved). It’s when Larry gets home from his tryst and starts flipping through his book of “forbidden” letters that Bressan launches into the film’s longest sustained color sequence, starting with the Halloween party where Larry first saw Richard, but didn’t dare talk to him.

It is here that Bressan returns to the adolescent fantasies and colorfully lit couplings that buoyed Passing Strangers, going above and beyond the point-and-shoot sex scenes that pornography has a tendency to reduce itself to. Larry’s brought back to reality, though, in time to have dinner with Iris, who bluntly tells him how much he and Richard are mismatched, but as their emotional reunion demonstrates, Bressan is more interested in highlighting the bond between them and all loving gay couples.

In the following decade, Bressan continued making X-rated films, plus two independent features exploring controversial topics in the gay community. The first was 1983’s Abuse, about a teenager with abusive parents who finds solace in the arms of a 30-something documentarian. The second was Buddies, which was out of circulation for decades before being restored and released by Vinegar Syndrome in 2018.

The final feature Bressan completed before his AIDS-related death in 1987 at the age of 44, Buddies charts the growing kinship between apolitical typesetter David (David Schachter) and Robert (Geoff Edholm), the AIDS patient he volunteers to buddy up with. Much like Tom and Robert in Passing Strangers, David and Robert share their stories, growing closer over time, although they do wind up arguing on multiple occasions. One of these occurs when David brings over a TV and VCR so they can watch that year’s Gay Day parade (actually reused footage from Gay USA), but they also use the set-up to watch one of David’s porn tapes. Naturally, this turns out to be Passing Strangers, which Robert fondly remembers seeing in San Francisco when it came out. That’s one unintentional way Bressan made sure his filmmaking career came full circle.

“Passing Strangers” will stream exclusively on PinkLabel.TV starting June 20, with “Forbidden Letters” following suit on August 22. The UCLA Film & Television Archive’s restoration of “Gay USA” is streaming on Amazon Prime and available on demand on Vimeo. “Buddies” is streaming on Kanopy and Vimeo and is available on Blu-ray/DVD from Vinegar Syndrome.