The shooting of Wim Wenders’ 1973 adaptation of The Scarlet Letter was not a happy experience. The filmmaker himself later admitted he wasn’t ready to helm such an ambitious period piece so early in his career, and the producers had shot down his choice of a male lead, Rüdiger Vogler – who’d appeared in the director’s The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick and would go on to serve as something of a cinematic alter ego for Wenders over the next 20 years. Even though the money men didn’t want him as their Reverend Dimmesdale, Vogler went to hang out during the shoot in Spain anyway, with Wenders giving his friend a small role as a sailor. It was during a scene Vogler shared with the eight-year-old actress playing Prynne and Dimmesdale’s daughter Pearl that the filmmaker saw a spark between the two and got an idea. Before they wrapped he’d already asked young Yella Rottländer if she wanted to make another movie next summer.

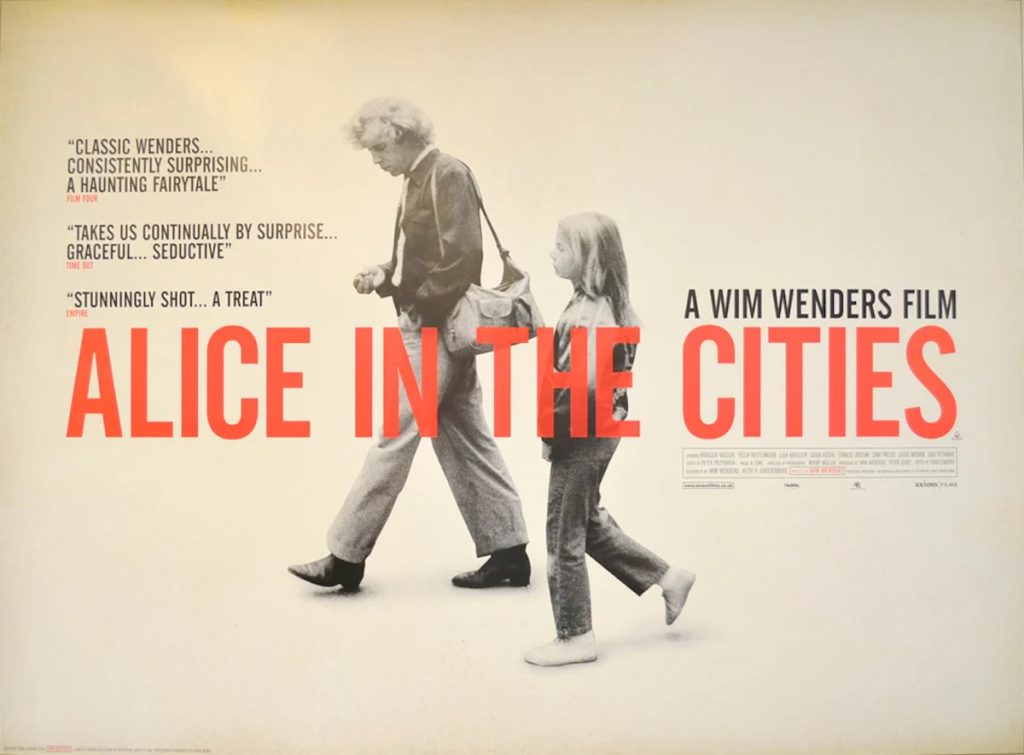

That movie, 1974’s Alice in the Cities, proved to be a breakthrough for Wenders, codifying the dreamy, sentimental existentialism that became his signature. Vogler stars as Phillip Winter – a surname the actor would have in several Wenders films – a depressed journalist with writer’s block, lost in America. Winter has been assigned to write an essay explaining the U.S. to German readers and he’s hopelessly adrift, taking Polaroids of desolate landscapes and driving around aimlessly, listening to rock n’ roll music on the radio. He gets himself fired and must return home. Eventually.

Into all this ennui drops Alice, a nine-year-old played by Rottländer in one of the movies’ great child performances. The little girl is visiting New York City with her flighty single mother (Lisa Kreuzer), currently inattentive in the midst of a bad breakup. There’s some difficulty getting tickets back to Germany due to an airline worker’s strike, so they all have to settle for flying to Amsterdam instead. Somehow, a friendly gesture from Winter turns into a babysitting gig, one that gets extended indefinitely when he’s looking through binoculars on the Empire State Building’s observation deck and spies Alice’s mom checking out of their hotel.

With all the garment-rending hysteria over child endangerment today – little girls in peril have become a fetish item for certain segments of the population – it seems far-fetched to the point of science fiction to imagine a woman entrusting her kid to a friendly stranger she’s just met, assuming that this kind fellow will get Alice to Amsterdam in one piece while she sticks around and sorts stuff out with her boyfriend in NYC. But perhaps things were different 51 years ago, or maybe Alice just has a terrible mom. Either way, there’s no movie if you don’t accept the premise, so roll with it and be rewarded.

Nothing about the trip goes according to plan. After a bevy of planes, trains, and automobiles, they finally get back home, where Winter is supposed to deliver Alice to her grandmother’s house. Except she doesn’t know where it is. Alice also doesn’t know her grandmother’s first name – she’s a kid, she calls her “Grandma” – so they wind up driving around all over Germany trying to find a house that matches an old picture Alice has in her wallet.

Winter is told earlier in the film by a former lover that he’s “become a stranger to himself,” and this miserable mope knows nothing about entertaining nine-year-olds. The great fun of Alice in the Cities is how he engages with the child as if she were a peer, gradually snapping out of his depression in her company. Alice isn’t a cute screenwriter’s creation who is going to teach him important life lessons, but rather an interesting little person he comes to enjoy spending time with. At one point Winter tries to do the responsible thing, leaving her with the police for them to handle it. But Alice gives these clueless cops the slip pretty quickly. By then she’d rather be with her buddy.

The old crank softening up under the influence of an adorable moppet is one of the movies’ oldest tropes, and it’s one that almost always works. (As someone who spends an enormous amount of his free time being bossed around by his nieces, I am especially susceptible.) But Wenders shoots this old Hollywood canard with artful, European restraint. Shot in gorgeous 16mm black-and-white by the genius cinematographer Robby Mueller — one of the best to ever do it — it’s a visual study of vast landscapes and bodies in motion, never getting anywhere.

Except they’re getting somewhere emotionally. Winter and Alice grow closer, imperceptibly at first, but by the end their bond has become enormously moving. None of this feels predetermined or orchestrated for the camera, perhaps because the film was mostly improvised, with non-professional actors filling out the bit roles. Wenders claims that he misplaced his copy of the script early in the shoot and never bothered getting another one. Instead he’d just tell his actors the gist of their scenes and let them feel their own ways through them. That’s why Rottländer’s Alice never comes off like a typical movie kid; she’s behaving like a real one would.

The director can be glimpsed at a diner jukebox early in the film, playing the Count Five’s “Psychotic Reaction.” It’s impossible to count all the jukeboxes, diners, highways, old muscle cars, and rock n’ roll in Wenders’ films, which seem to run on an outsider’s dreams of an idealized Americana. At a low point, Winter attempts to cheer himself up by going to a Chuck Berry concert. The clumsily intercut footage is borrowed from a D.A. Pennebaker doc and doesn’t match Mueller’s lighting at all, but that doesn’t matter because Wenders simply had to get Chuck Berry singing “Memphis, Tennessee” in his film. Understandable.

Winter is the filmmaker’s stand-in, trying in vain to explain what he loves and fruitlessly piling up Polaroid photo after Polaroid photo of these sparse landscapes and open roads, throwing them aside and complaining that the camera can never capture life the way you see it. It’s only after his trip with Alice that he starts taking pictures with people in them.

“Alice in the Cities” is streaming on the Criterion Channel.