Martin Scorsese is no stranger to controversy when it comes to the violent and shocking images in his films. As the man himself remembers in the recent Apple TV docuseries Mr. Scorsese, he famously had to alter the color grading of the climax in Taxi Driver so the blood wouldn’t warrant an X rating (the precursor to the NC-17); Gangs of New York made multiple headlines for its gory battle scenes (amusingly enough, this writer was living in Italy at the time of release, and the movie sparked debate after receiving the local equivalent of a G rating); Raging Bull’s script was so lurid, he and Robert De Niro actually went ahead and softened some of the more objectionable material; and so on, and so forth.

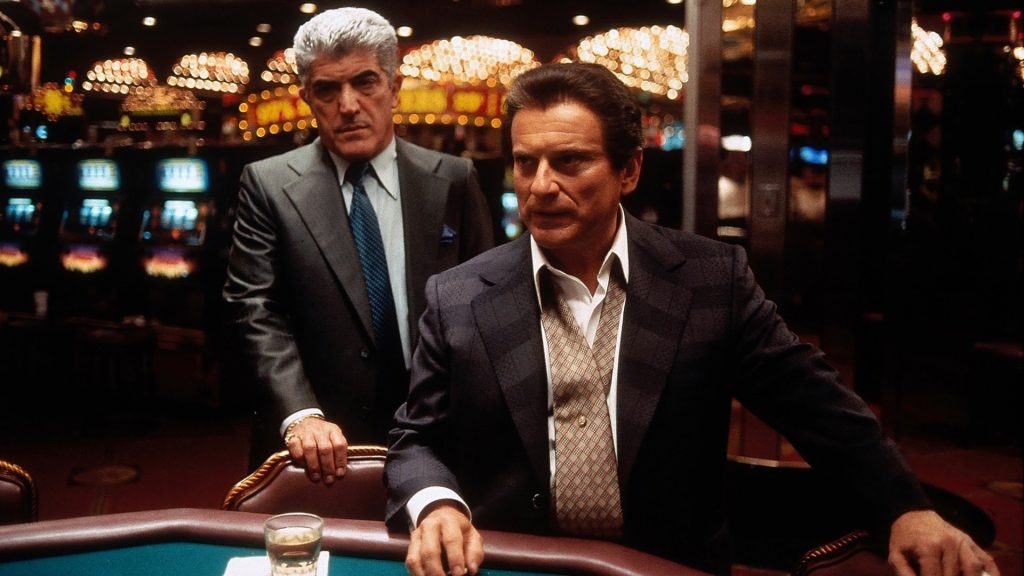

But no story is more memorable than the one surrounding a specific moment in Casino, the 1995 mob drama based on Nicholas Pileggi’s non-fiction book about Sam “Ace” Rothstein (De Niro), a mafia associate from Chicago (referred to as “back home” in the film for legal reasons) running a gambling establishment in Las Vegas on behalf of his bosses. Its notoriously brutal moments almost invariably involve Joe Pesci’s Nicky Santoro, a mobster with an extremely short fuse and no shortage of creative methods to dispatch his enemies – early in the movie, he fatally stabs a guy with a pen.

That’s nothing, though, compared to the single most disturbing depiction of violence in Scorsese’s oeuvre: the infamous “head in a vise” scene, where Santoro tortures a man by squeezing his head until one of his eyes pops out. It’s a moment that occurs in Pileggi’s book, albeit in a different context, while still involving Santoro, or rather, his real life counterpart Anthony Spilotro. The real incident was apparently even more wince-inducing than the movie version, as both eyes popped out (conversely, Santoro’s eventual comeuppance was far more ordinary on the page).

It’s a hard scene to watch, something the filmmakers were quite aware of since, by all accounts, the sequence was never meant to be included in the final cut of the film. What happened was, Scorsese knew the Motion Picture Association would give him a hard time over the numerous other brutal incidents that occur in the movie, which come with an extra serving of extensive profanity (until the 2013 release of The Wolf of Wall Street, this was the Scorsese picture with the most F-bombs, 422 in total; Wolf has 569). Business as usual, one might say. But since the violence was an integral part of the movie’s depiction of greed and power, the director wanted to make sure the censors didn’t tamper too much with the material.

Thus, the vise scene was born. In Scorsese’s mind, it was meant to shock the MPA to such an extent, they would request its removal and overlook all the other moments of violence sprinkled throughout the film. It’s a strategy other filmmakers have adopted: in 2004, Trey Parker and Matt Stone, whose battles with the ratings board are well documented, submitted a cut of Team America: World Police where the notorious puppet sex scene had additional shots that were guaranteed to earn an NC-17. The version seen in the final, R-rated edit is the one they were planning to show all along.

Much to Scorsese’s surprise, though, no particular objections were raised over the vise scene specifically. The initial NC-17 decision came with no demands that any individual sequence be removed, and so the (literally) eyepopping moment stayed in, although some minor edits were made to secure an R. What was intended as a sacrificial lamb, a pawn left out in the open to protect the queen, became one of Casino’s signature scenes, and another example of Scorsese going where few, if any, other American directors dared to venture.

Still today, three decades after its original release, the movie stands proudly as one of the director’s most grandiose achievements, on a double bill with Goodfellas as the perfect encapsulation of the real life tragedy of mob life and the hubris that comes with it (with 2019’s The Irishman, once again reuniting De Niro and Pesci, serving as a coda of sorts). That it hits as accurately and mercilessly as it does is due in no small part to how it doesn’t hold back, and one wonders what may have occurred in a different timeline, where the vise scene never left editor Thelma Schoonmaker’s office. The movie would still work, but it probably wouldn’t pop as much—pun very much intended.

“Casino” is streaming on Hulu and Tubi.