For Orson Welles, the 1950s was a time of self-imposed exile from Hollywood. (Among other things, as a staunch leftist, he was eager not to get swept up in the prevailing anti-communist witch hunts.) It was a time of working in Europe and periodically getting the financing together to put one of his own projects before the cameras. His last American film, 1948’s Macbeth, had been made for Republic Pictures, which was best known for its serials and westerns, and released a heavily edited version redubbed to tone down the Scottish accents. His next Shakespeare production, Othello, ran out of money multiple times, forcing Welles to go off and act in other films to earn enough to continue. (As would come to be standard practice for him, Welles improvised around the situation, shooting what he could with what he had, and piecing it all together later on.)

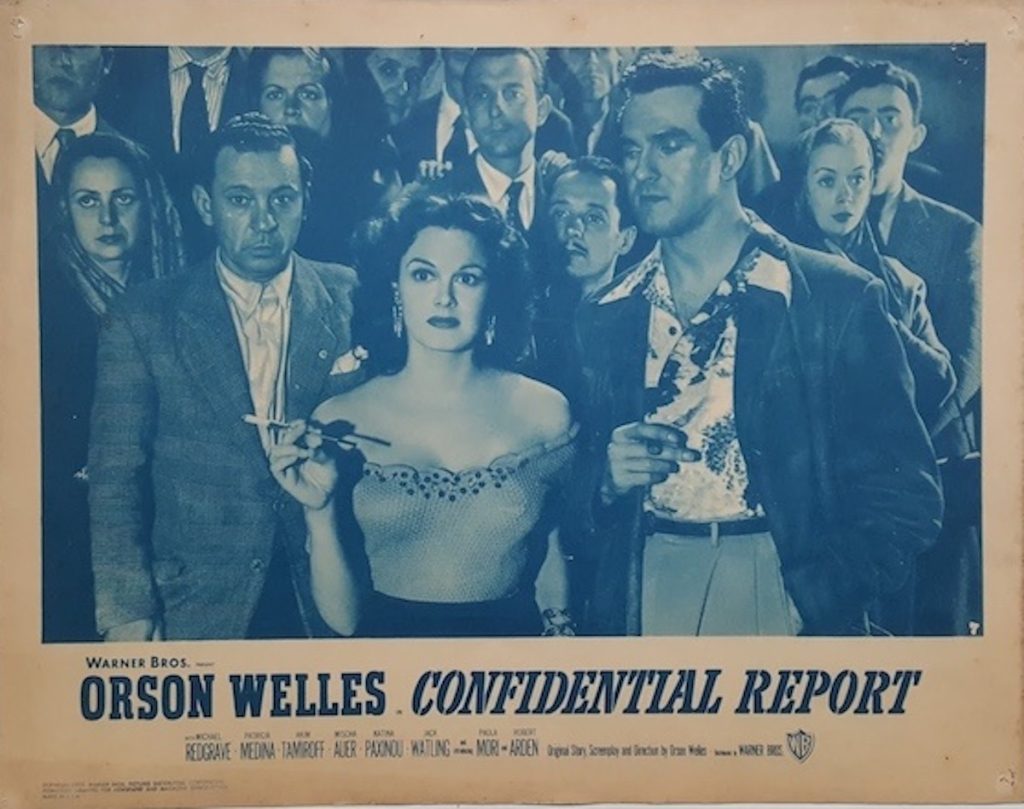

Like Othello, which screened at Cannes under the flag of Morocco, his next film, Mr. Arkadin, was an international co-production. Largely filmed in Spain, Mr. Arkadin premiered in Barcelona on June 27, 1955, about a month and half before a different version opened in London under the title Confidential Report. Unlike Touch of Evil, which was eventually reconstructed based on Welles’s detailed instructions (submitted in the form of a memo to Universal after he was barred from the editing room), there is no definitive cut of Mr. Arkadin that conforms to Welles’s vision because it isn’t known.

That said, there is a “comprehensive version” cobbled together from various sources and released by the Criterion Collection in 2006 as part of The Complete Mr. Arkadin (which also comes with a reprint of the novelization, a work credited to Welles, but penned by someone else). Whichever version one watches, it can be a dizzying experience, and not just because Welles uses lots of canted angles, quick cutting, and noir shadows. It’s a wild adventure set in far-flung locations stocked with all manner of eccentric characters who each have a piece of the puzzle needed to answer the question “Who is Gregory Arkadin?” It’s the all-important question, too, since the person who most wants to know the answer is the man himself.

The bulk of the story plays out in flashback as small-time smuggler Guy Van Stratten (Robert Arden, who gets an “introducing” credit alongside Welles’s then-lover and soon-to-be-wife Paola Mori) recounts how he got entangled with a reclusive businessman of foreign extraction – but how foreign and from where was he extracted? Naturally, Arkadin is the role filled by Welles, who wears a theatrical wig and beard, but delays his entrance (shades of The Third Man) while Guy and his lover Mily (Patricia Medina) take a two-pronged approach to get close to him. Their hope is for a big payoff; what they get is the runaround.

Since Mily is a beautiful woman, it’s easy enough for her to find her way onto Arkadin’s yacht, and eventually gain his ear. As for Guy, his entry point is through Arkadin’s daughter Raina (Mori), who is under constant observation by her father’s “secretaries” (a euphemism for spies). While Arkadin disapproves of Guy as a suitor, and has the dossier to prove how disreputable he is, he’s just the right man to send trotting around Europe, prying information out of other seedy types played by the likes of Peter van Eyck, Michael Redgrave, and Akim Tamiroff. (Tamiroff quickly became one of Welles’s go-to actors, returning in Touch of Evil, The Trial, and the ill-fated Don Quixote, in which he played Sancho Panza.) Meanwhile, Arkadin himself meets with an elusive baroness played by Suzanne Flon, one of two actresses replaced by another performer for the Spanish version. “Digging into the past, it’s really too disgusting,” the baroness tells him, neatly summing up the film as a whole.

As the film’s ostensible lead, Arden is more than a little outclassed and out of his depth, but that works in a way, since his character is supposed to be as well. To compensate, Welles delivers an outsize performance as the larger-than-life Arkadin, and gives himself the film’s most memorable speech, a telling of the parable of the scorpion and the frog that is the equal of the famous cuckoo clock speech in The Third Man (one of the films he appeared in during Othello’s protracted production). What he couldn’t give himself was enough time to finish editing the film before his producer took it away from him, causing a rift between them and Welles to disown the final product(s). It wasn’t long, though, before he was back in Hollywood with what he believed to be a three-picture deal at Universal and the ability to make films on his own turf. Home at last, but not, alas, for long.

“The Complete Mr. Arkadin” is streaming on the Criterion Channel. The incomplete “Mr. Arkadin” can be found elsewhere.