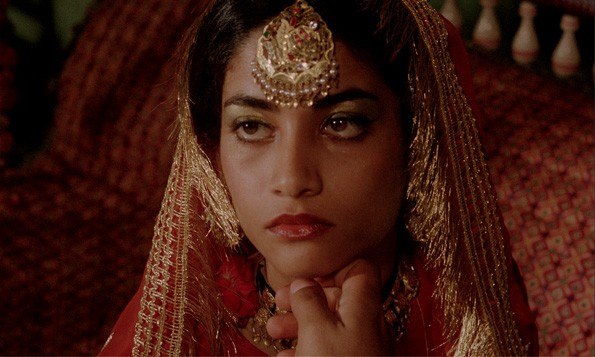

A flute serenely plays over a cotton picker performing quotidian tasks. The laborer is the daughter of a trusted contact for a landowner who is based in the Punjab region of Pakistan. On her way home, she bumps into the owner, the modest Hussain, and though she does not converse with him (minus an upset look), the soft-spoken landlord fondly stares at her, registering affection and love. Following local custom, Hussain will soon ask the woman’s father to marry her, and he will succeed, wedding the “beautiful girl, with long black hair” despite her looks of dismay and apathy.

Such subtle depictions of local cultures and relationships in Pakistan lie at the heart of Jamil Dehlavi’s The Blood of Hussain, a criminally underseen work that continues to be banned in Pakistan for anti-army content (the military declared martial law a month after shooting wrapped in 1977). Save for a 2018 BFI re-release, the film has endured a largely invisible existence, with a version on YouTube generating a mere 35,000 views – a shock, especially considering that it is among the most acclaimed films made by a Pakistani director. Winner of the 1981 Taormina Film Festival, as well as a selection in the director’s fortnight at the 1980 Cannes Film Festival, The Blood of Hussain traces a truculent sibling relationship between the banker Selim and local landlord Hussain (both played with stunning aplomb by the charming British-Pakistani actor Salmaan Peerzada). With Pakistan taken over by the tyrannical army that is led by a deceptive and corrupt general (a short-tempered Mirza Ghazanfar Begg), the westernized Selim is tasked to negotiate loans with the World Bank while Hussain defends local farmers from the army’s seizure of private property.

While the film appears to be more sympathetic to Hussain – the Islamic story of the prophet’s grandson Imam Hussain battling the despot Yazid is mapped onto the film’s hero’s struggles against the army – it manages to offer generative criticisms. Dehlavi critiques the local culture through exposing the gender dynamics at play. When Selim attends a local brothel, a male procurer handles the transaction for a female sex worker, mirroring the marriage proposal about which Hussain inquires with his future father-in-law. Men dictate decisions for women, who, in both sequences visibly suffer – Selim forcibly kisses and overpowers the sex worker as the procurer refuses to help.

Religious customs are also evaluated. Consider the sequences of the mourning of Murraham, a ceremony dedicated to the death of Imam Hussain, when followers flagellate and beat themselves. The film ends hypnotically as the general and his right-hand man Zahid (played by Dehlavi) stare disturbingly at the ceremony outside. As blood splatter fogs up the lens, we drape the onlookers’ gaze and the questions posed are of weighty implications: Is the suffering worth this bodily sacrifice? Is such fanaticism a viable alternative to imperialism?

The film’s remarkable production history helps reveal power relations. When the ban was issued, Dehlavi’s passport was confiscated. The director luckily escaped and lived in England, ironic given the influence of Westernization on the army. In the film, army officials mostly converse in English, a contrast to the locals who speak in Punjabi, the Punjab region’s main language. The army officers appear to be modernized by the Western apparatus through their modern clothing, starkly dissimilar to the traditional salwar kameez worn by locals.

In her work on postcolonialism and Pakistan, Shazia Rahman has explored the challenges of finding a nuanced analysis of the country, explicating the common trap of substituting imperialism with religious extremism for “anti-imperialism has historically been linked with religious nationalism in the region.” Dehlavi confounds such static positionality through his French and Pakistani roots as well as his multinational education in Pakistan, America, and Britain. The director’s filmography deals with the futility of a defined positionality, as his subjects range from jinns, trans communities and immigrants. In his films, such ignored beings clash with dominant power structures and ideologies.

In The Blood of Hussain, who/what is repressed is not only the populace, but a nuanced imaginary. In the opening scene, a soothsayer explains to a teenage Hussain that he originates from the “tomb of the future, circle of the present.” In depicting violent conflicts surrounded by extreme religious ideology, political corruption, and cultural conservatism, Dehlavi’s greatest achievement is to frame such conflicts as extraordinarily mournful of the project of Pakistan, the logical conclusion and future of the country’s embattled past and present.

Though press for the film’s acclaimed British opening in March 1981 mostly spoke to the depiction of the oppressive regime, The Blood of Hussain is rueful about several layers – not just the army – of Pakistan. Cinematographer Walter Lassely’s naturalistic images of laborers walking through fields or riding camelback over the graceful sounds of flute suggest a country unencumbered by difference and conflict. In these gentle moments, Dehlavi’s film highlights life emanating from within the country without the external pressures of martyrdom and imperialism. However, such moments are brief, and ultimately disrupted and ruptured.