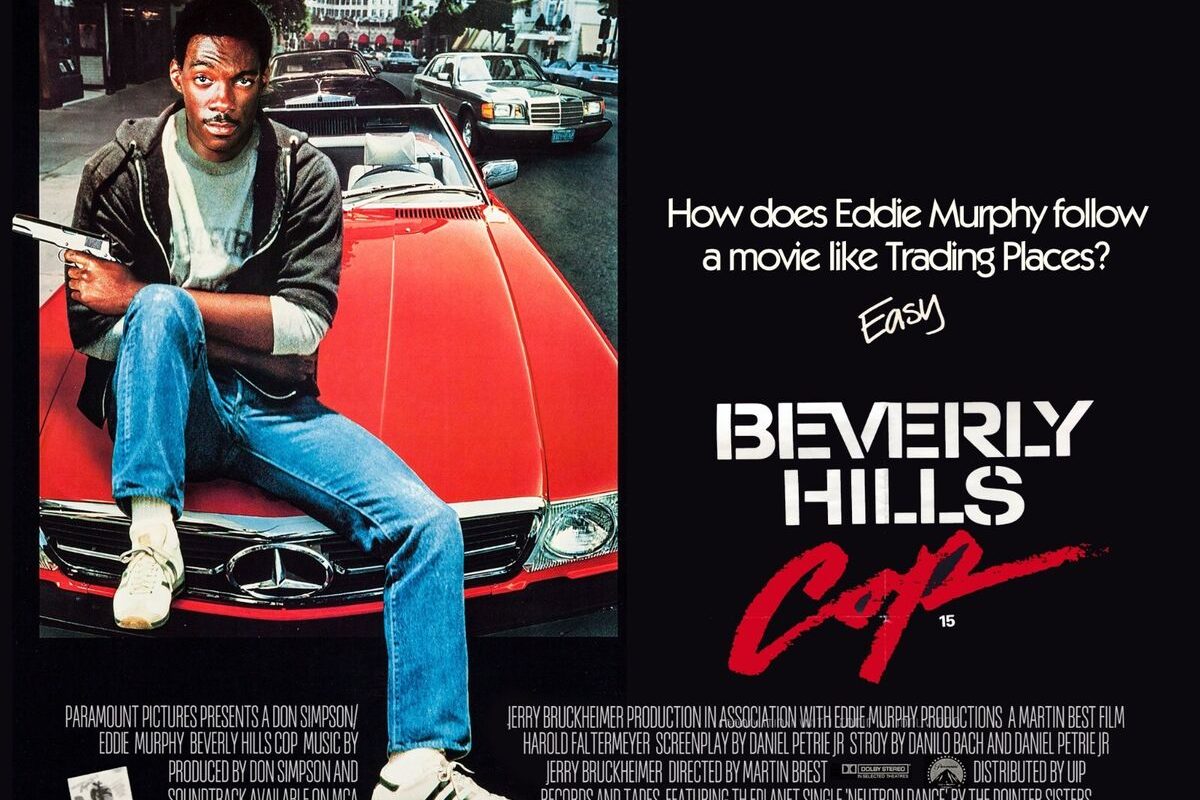

Axel wasn’t originally supposed to be Eddie.

Riding high from the success of Flashdance, producers Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer revived a stalled-out pet project of Simpson’s called Beverly Drive, about a tough Pittsburgh cop named Elly Axel who chases a case to sunny California. Up-and-coming scribe Daniel Petrie Jr. was brought in to rewrite Danilo Bach’s original script, with Mickey Rourke signed to star as the detective whose name was flipped to Axel Elly. Martin Scorsese is said to have turned down an offer to direct the project, claiming the premise was too close to Don Siegel and Clint Eastwood’s cowboy-in-New-York hit Coogan’s Bluff. David Cronenberg also passed (the mind reels) with the assignment going to a young filmmaker named Martin Brest, who’d recently been fired two weeks into shooting his second theatrical feature, WarGames.

By that point Sylvester Stallone had become attached to star, re-writing Petrie’s script as was his usual custom. The character was rechristened Axel Cobretti and the budget-busting action sequences he’d added included playing chicken with a freight train in a stolen Lamborghini. He also got rid of all the jokes. Eventually, the producers finagled their way out of Stallone’s pay-or-play contract by allowing him to keep his rewrites and the Cobretti character, whose first name Sly changed to Marion when the material that would have been Beverly Hills Cop became the basis for his putrid 1986 thriller Cobra.

A couple of weeks before cameras rolled, Simpson and Bruckheimer hired Eddie Murphy, and that’s when Axel Foley was born. The casting seems like a no-brainer now, but back then you didn’t see 23-year-old Black comedians headlining their own major studio holiday releases. (You still don’t.) Murphy had been dynamite opposite Nick Nolte in 48 Hrs. and Dan Aykroyd in Trading Places, but this was his first time carrying a movie on his own, without the top-billed white guys that even his idol Richard Pryor had to co-star with. There was trepidation in the front office, but Brest saw the genius of the casting choice right away. He cited the star-making sequence in 48 Hrs. when Murphy brought a redneck saloon to heel by sheer force of personality, saying to the producers, “Oh my god, we could have a full-length version of the bar scene.”

Axel Foley might be a more overtly heroic character than the felon Murphy played in 48 Hrs. but Beverly Hills Cop is indeed a breezier expansion of the scene that made him a movie star. Looking to solve the shockingly brutal murder of his childhood friend Mikey Tandino (James Russo), our Detroit cop pays a visit to California’s fanciest zip code and starts sniffing around the imports and exports of a rich, respected art dealer (Steven Berkoff) who reeks of decadent ‘80s movie villainy. The plot is by-the-numbers TV cop show stuff; what matters is the rapport that Murphy has with the two straight-arrow policemen assigned to babysit this meddlesome out-of-towner. What matters even more is his rapport with the audience.

If you weren’t there, it’s difficult to understand just how completely Eddie Murphy dominated popular culture at that moment. After the blazingly charismatic performer single-handedly saved Saturday Night Live (who could even share the credit, Piscopo?), his comedy albums and the concert film Delirious taught my entire generation of schoolkids how to say swears. Beverly Hills Cop finds Murphy at the precise height of his powers, spreading his wings as a surprisingly credible leading man and taking over a routine police picture the same way Axel talks his way into a suite at the Beverly Palm Hotel — by improvising some beautiful bullshit.

Murphy, Petrie and Brest would spend every morning on set writing the scenes they were about to shoot, re-configuring the film as an action-comedy hybrid in the tradition of Busting or Freebie and the Bean but a little lighter and less abrasive. Beverly Hills Cop is an extremely easy movie to watch, floating from scene to scene on the chemistry between these characters and Murphy’s incandescent charm. A Black man with a wardrobe of jeans and tattered sweatshirts is a walking affront to the moneyed exclusivity of Beverly Hills. Yet Axel can talk his way in anywhere, the same way we’re watching Murphy strut his way onto Hollywood’s A-list. He bends the picture to his personality, turning an action movie that was originally written without jokes into one of the highest-grossing comedies of all time. (The film’s box office haul would total more than $950 million in today’s dollars.)

The filmmakers were shrewd to focus on Axel’s slow-growing friendship with his minders Taggart and Rosewood, a Laurel and Hardy duo played with great aplomb by John Ashton and Judge Reinhold. Ashton is one of those guys who was born looking 50 years old, while Reinhold gazes at the world with the wide-eyed wonder of a newborn. Axel taunts and teases them good-naturedly, while imparting important lessons like how to lie to your boss. The movie is full of memorable bit players who pop up for a scene or two. Little did we know then that Jonathan Banks would still be playing a variation on this hitman 25 years later on Breaking Bad, while Bronson Pinchot built an entire career off of his imperious gallery attendant Serge, with an unplaceable accent that carried him through eight seasons of Perfect Strangers.

Beyond Harold Faltermeyer’s instantly iconic synth theme, the soundtrack bounces along to tunes from The Pointer Sisters, Vanity and Patti LaBelle. Despite some surprisingly graphic violence, Brest maintains a convivial party atmosphere throughout. Beverly Hills Cop might not be a great movie, but it’s a great hangout movie. Part of Murphy’s gift is inviting the audience along so that we feel like his co-conspirators. No comedian has a more contagious laugh – co-star Lisa Eilbacher even tries to mock it in the film – and so much of Axel’s schtick involves cracking himself up, like he can’t believe he’s getting away with this shit, either.

Murphy would never reach such heights again. When Axel Foley came back to California three years later the character had already soured somewhat, his motormouth routine becoming hectoring and vain. Directed by Tony Scott, the flashy, ultra-violent Beverly Hills Cop II felt more like a sequel to the unmade Stallone version. (The less said about Cop III the better. And while I know that I saw and reviewed Netflix’s Beverly Hills Cop: Axel F last summer, I recently had to be reminded it was a thing that existed.)

Like Brest’s follow-up feature Midnight Run, Beverly Hills Cop is a picture that wears even better on repeat viewings because we already know and love these characters. The generic nature of the crime story somehow makes it even cozier, with familiar beats that don’t take too much focus away from the people we’re enjoying. There’s something awfully welcoming about Beverly Hills Cop. You can see why it spent 14 weeks at the top of the box office. The movie is good company.

“Beverly Hills Cop” is streaming on Paramount+, Kanopy, and Hoopla.