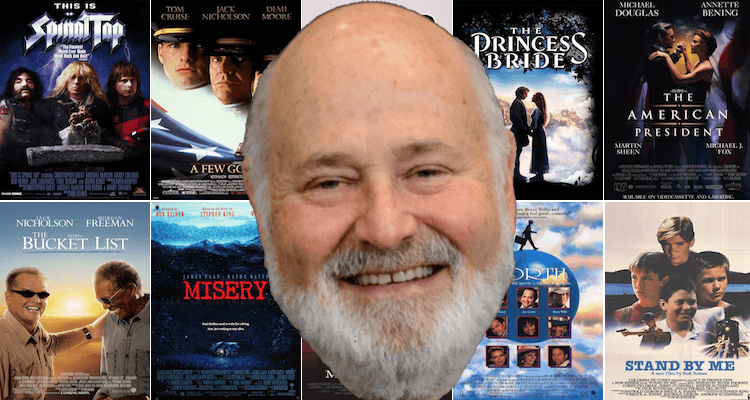

Rob Reiner is not exactly the first name that pops up when people list their favorite directors — usually those lists include people like David Fincher, Stanley Kubrick, Christopher Nolan, Martin Scorsese, Wes Anderson, Michel Gondry, and others with more of an auteur imprimatur. Yet Rob Reiner has directed more 20 feature films since his 1984 debut, the rockumentary classic This Is Spinal Tap; his credits include the charming, sly rom-com When Harry Met Sally…, a collaboration with the late, great Nora Ephron; the two talky-political Sorkin scripts A Few Good Men and The American President; the frankly adorable The Sure Thing, starring a baby-faced John Cusack; and the hilarious, fantastical The Princess Bride. For many observers, though, Reiner’s been in a slump since The American President, a slump that has only recently started to lift with the generally positive reception to 2015’s Being Charlie. Now the new LBJ, starring Woody Harrelson, Richard Jenkins, and Bill Pullman, offers another chance at a Reinerssance.

Whither that 20-year gap? And what makes these earlier projects of Reiner’s succeed, while films like The Bucket List, Rumor Has It…, And So It Goes, Ghosts of Mississippi, North, and Alex & Emma have lukewarm to downright ice-cold critical receptions? Are Reiner’s late works really so bad as to push his earlier successes into the rearview?

With many of Reiner’s less-loved films, the plot hinges on a gimmick — an event that happens merely for the sake of making a movie. The hackneyed setup of Rumor Has It…, where the protagonist learns that The Graduate was based on her grandmother, requires such a suspension of disbelief that everyone would be making a big deal out of this coincidence that it drags down the performances.

Similarly, The Bucket List exists for its own sake because something needs to happen: two elderly cancer patients from totally different backgrounds decide to become friends and carpe all of the remaining diem before they die. Alex & Emma imposes the arbitrary 30-day timeline to finish the protagonist’s novel, with the lurking threat of the Cuban mafia. North, which was famously panned by Roger Ebert, features a child genius traveling the world to audition new parents. And So It Goes has the cliche of the previously unknown child (or grandchild, in this case) who gives Michael Douglas a new lease on life and teaches him how to be a good person. And while Morgan Freeman’s writer character in The Magic of Belle Isle doesn’t start off as a jerk, it just takes a beautiful vacation and the love of the family next door to help him get his spark back. Indeed, The Bucket List, And So It Goes, and The Magic of Belle Isle go through the same beats: protagonist (or plural) of distinguished age gets back in their groove/learns to love again/finds a reason for living through contrived and at times maudlin means.

In contrast, the best of Reiner’s films share a common quality rather than a common story structure: they’re light, clever, a little talky, and sweetly sarcastic. What unites these films, specifically, is Reiner’s deft touch, which balances the more serious aspects of the subject matter. Yet the subject matter, with the exception of A Few Good Men, never gets truly dramatic or serious, and it’s always grounded in small, everyday truth. People fall in love in complicated ways (When Harry Met Sally…, The American President), people grow up and lose their innocence and expectations about how the world should be (Flipped, A Few Good Men, The Sure Thing, Stand By Me), friendships necessarily change form (This Is Spinal Tap, Stand By Me). There’s the assumption of kindness, of good intentions, and of people trying to do the right thing.

A Few Good Men, Spinal Tap, The Princess Bride, and The American President, while vastly different in plot and setting, do all share a common theme: they are about delving into idiosyncratic other worlds and environments, whether they’re a medieval fairy tale, the walky-talky White House, the rock-’n’-roll lifestyle, or the highly regulated and secretive community of the U.S. military. The relationship of the audience to these subcultures is paramount, as we’re led into a totally unfamiliar and specific world. A Few Good Men puts us in the shoes of the relatively green Tom Cruise and Demi Moore, where we learn first-hand what they do about corruption, cruelty, and power. In The American President and Spinal Tap, we’re flies on the wall, enjoying the witty romance of President Shepherd and Sydney Ellen Wade and laughing at the foibles of the eponymous band. The Princess Bride imagines us sitting on the edge of Fred Savage’s bed, listening to Peter Falk wax poetic about giants, adventure, and a little kissing.

It is in the context of assessing Reiner’s later work, however, that I do want to draw attention to Flipped as a model for a Reinerssance movie. It’s an adaptation of a tween-age book and unfortunately flew under the radar upon its release in 2010; it’s hardly on the level of Spinal Tap and Princess Bride in terms of sheer mastery of narrative, tone, and casting, but it’s certainly as good as The Sure Thing, and fits well within Reiner’s established playing field of romance, nostalgia, and loss of innocence. The screenplay, co-written by Reiner, immediately takes a bold step in transporting the action of the novel back to the 1950s and ‘60s (the original narrative takes place in the 1990s), creating ample opportunities to really drive the point of the story home. In the America of the 1950s, plenty of darkness lurks behind white picket fences and perfectly trimmed foliage, which only begins to rear its ugly head during the tumultuous ‘60s. We see precisely this cultural shift happen in Mad Men, and the decision (a decision in which Reiner undoubtedly took part) to cast the novel’s traditional coming-of-age narrative — and the destruction of childhood’s rose-colored glasses — during this time period has a wonderful parallel quality. It doesn’t emulate the dramatics of Ghosts of Mississippi in its interrogation of prejudice, but instead frames them very much within the child’s eye view — which is perhaps one reason Reiner’s (likely) Boomer-aged usual audience didn’t find Flipped compelling.

LBJ is Reiner’s first biopic, so evaluating it within the context of his oeuvre will perhaps require the establishment of another framework. Certainly, it’s starting off on a good foot; when Reiner worked with acclaimed scribes Sorkin and Ephron, the results were strong, and LBJ’s script (by Joey Hartstone) was on the 2014 Black List. Reiner’s comfortable with the rapid pace and mannered behavior of Washington politics as seen in The American President, and the idea of a President with good intentions — even if his behavior is imperfect — might resonate in 2017 as a comforting fiction. There’s hardly room for any of the tired Bucket List/Belle Isle/And So It Goes beats to sneak into a fact-based story; if the movie were about a post-presidency Johnson looking back on his tenure, that would be cause for concern, as the Reiner model would likely require the goodness of children to give a grouchy Johnson meaning in the winter of his life.

Deborah Krieger lives in Philadelphia, can handle the truth.