Though titled simply Golda, this film about the Israeli prime minister isn’t an all-encompassing biopic spanning Golda Meir’s 80 years on earth. Instead, director Guy Nattiv’s gripping drama focuses on a single pivotal event in the politician’s life: the 19-day Yom Kippur War in 1973 and the ensuing investigation in the Agranat Commission the following year. Other than small snippets of dialogue, we are given little of her biography beyond this brief time. Yet between the sharp characterization in Nicholas Martin’s script and an equally precise performance from Helen Mirren, the audience has a clear idea of who Meir is: an uncompromising leader who could make difficult choices while never losing sight of every human affected by them.

In the screenwriting bible Story, Robert McKee wrote, “True character is revealed in the choices a human being makes under pressure — the greater the pressure, the deeper the revelation, the truer the choice to the character’s essential nature.” It’s difficult to imagine a more stressful time that what we see of Meir’s experience here: not only is she dealing with an attack by Egypt and Syria that threatens to annihilate Israel just decades after its hard-won founding, but she also is the nation’s first female prime minister, and she is secretly seeking treatment for lymphoma. If all this was in a purely fictional script, a screenwriting teacher might warn his student that it’s one conflict too many for a protagonist: can’t she just be breaking the glass ceiling and struggling with cancer? Or could it be a male politician simultaneously fighting illness from within and an attack on his country’s borders?

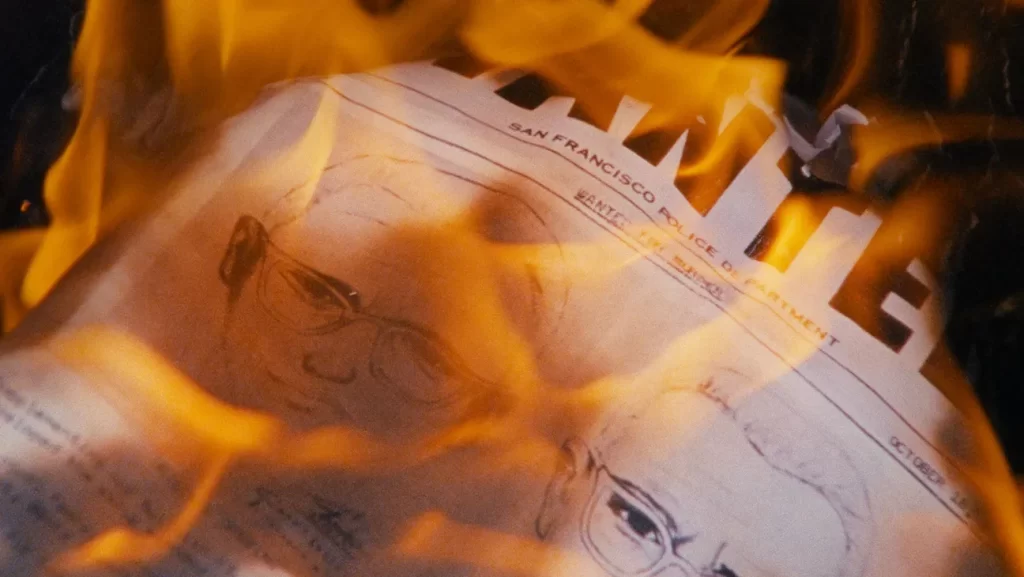

Yet the real Meir did face all of these challenges at once, and Nattiv imbues Golda with a resulting sense of claustrophobia. Tight close-ups zero in on Mirren’s impeccably made-up face, which is believably transformed into Meir’s visage. We see her nicotine-stained fingers as she smokes cigarette after cigarette. Shots of hallways make it seem like the walls are closing in on Meir, as she is left with few good options to defend both Israel and the individual soldiers fighting for it. Cinematographer Jasper Wolf’s camera shudders toward the action, with a halting movement that is visually interesting but occasionally distracting. Flashes of real-life footage from the war are intercut into scenes, and audio recordings from the front lines make moments in the war room feel like they’re on the battlefield. The score from Dascha Dauenhauer turns every instrument into percussion, creating a tense atmosphere for the film’s 100 minutes.

Golda is almost relentlessly — and appropriately — solemn throughout its running time; its biggest joke might be about Henry Kissinger (Liev Schreiber) feeling obligated to eat a Holocaust survivor’s borscht. While there’s an immense gravity to the proceedings, that thematic weight is not without merit. Thousands died in the Yom Kippur War, and Meir takes literal note of them all, adding casualty numbers to a notebook she carries with her. Meir is stubborn and sure, but she’s also filled with warmth and a wry sense of humor amidst the pressure. Golda skates over mentions of her family, but her affection for those around her, especially her aide, Lou Kaddar (Camille Cottin), is obvious, as is how much she cares about the fate of each person in her country, not just Israel as a whole.

Yet for all of Meir’s concern for her people, Golda left me oddly cold. It depicts a harrowing tragedy that affected a nation, but it doesn’t really leave a mark, even with its unconventional approach. Outside of Mirren’s predictably great performance, Golda sometimes lacks subtlety and nuance. Did we need a winking line predicting General Ariel Sharon (Ohad Knoller) would become prime minister himself in the future? This brief scene takes you out of a film that is all about establishing a sense of immediacy for the sake of Israel, its soldiers, and Meir and her health. Similarly, “Who by Fire” — written by Leonard Cohen and inspired by his visit to Israel during the Yom Kippur War — closes the film. The song is a little too on-the-nose, though still affecting, choice for a needle drop. Golda also refrains from contending with how controversial Meir is for some. Other than her chain-smoking, the film presents a picture of a person wholly to be admired, leaning a bit too much toward hagiography.

Though Golda only depicts a few weeks in Meir’s life, it creates a detailed picture of the prime minister as a character (albeit one largely without flaws). At once tough and tender, Golda’s Meir is worthy of admiration. Meanwhile Nattiv’s film isn’t quite on the same level as its subject in either its achievements or staying power in the audience’s memory.

B-

“Golda” is in theaters Friday.