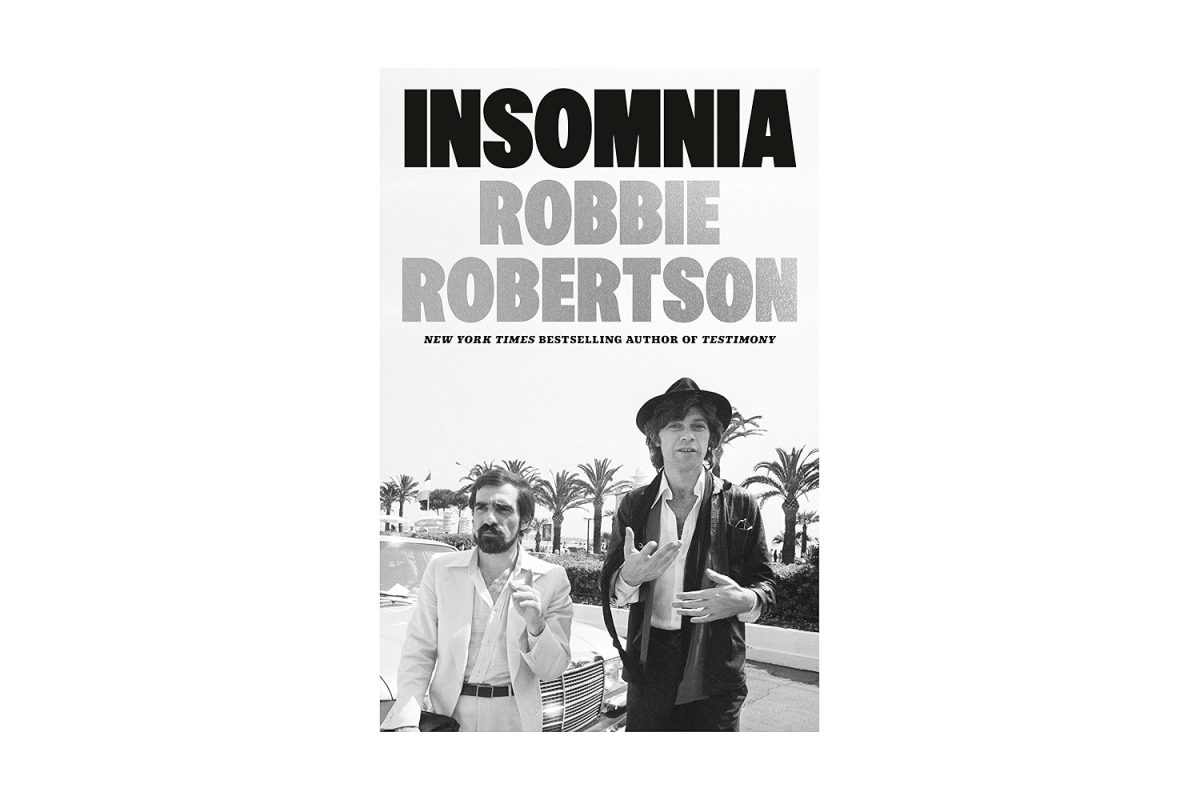

There’s a clip that goes viral every once in a while from an old BBC documentary about Robbie Robertson and Martin Scorsese. The year is 1978, and the two are on a press tour promoting The Last Waltz. It’s just before dawn in a London hotel room, where a woozy documentarian is having a hard time keeping up with his subjects. “Maestro,” Robertson purrs to his pal in a slow, sleepy voice, “I want to play you a song before we knock off.” The song is Van Morrison’s “Tupelo Honey,” which sends Robertson into a zonked reverie of dreamy head nods while Scorsese, excitedly nibbling on his little finger, keeps fidgeting and grinning devilishly – everything he did looked devilish in that era – shaking his head in awe of what he’s hearing. Light begins to peek through the hotel windows, and the spell is broken. “Dawn!” Roberston announces.

We’ve all had moments like that with a friend, when you’re up too late and wasted, then you hear the perfect song. For three or four minutes there’s no BBC documentary crew or promotional obligations in the morning or sunlight creeping along the horizon, it’s just you and your buddy being transported by a beautiful piece of music. (And music doesn’t get much more beautiful than “Tupelo Honey.”) In his wonderful remembrance of Roberston for Rolling Stone, Scorsese wrote that when the sun was coming up, “The only thing left to do was to put on ‘Tupelo Honey.’ That’s what always happened. Van and ‘Tupelo Honey.’ It was sort of our sign off.”

Robertson and Scorsese had a lot of nights like that, many of them recounted in Robertson’s posthumously published Insomnia. During post-production on The Last Waltz, the musician was separated from his wife Dominique and sleeping in The Band’s Shangri-La studio. He wound up moving in with Scorsese, whose second wife Julia Cameron had recently left with their daughter Domenica. The rock star and the movie director became what Robertson describes as a “whacked out new version of The Odd Couple” for a lost weekend that lasted about a year and a half. The two famously soundproofed the Beverly Hills house and installed blackout shades, staying up until all hours every night partying, listening to music and watching old movies. Robertson says, “We were, as the Indians say, walking in the beauty way.”

Insomnia is a gentlemanly tour of late-‘70s Southern California decadence, full of eyebrow-raising anecdotes and delicious name drops. But mostly it’s a love story about two best friends who not-so-secretly want to be each other. Scorsese has always shot and cut his movies like a frustrated musician, while Robertson’s richly cinematic songs for The Band were written and “cast” with roles for the group’s three singers. The two are desperately hungry to learn more about each other’s disciplines, and both are natural born curators. One of the things that comes through most powerfully in the book is the thrill of turning a pal on to something you love that you know they’re gonna dig. Come for the coke binges and gorgeous gals, stay for the lengthy digressions about Sam Fuller and the Staple Singers.

Robertson writes about everything in a breezy, appreciative tone. He’s constantly marveling at all the great artists in their orbit and the beautiful women who seem so eager to bed down with him, euphemizing the ubiquitous drugs as “party favors” or “a little pick me up.” Maybe it’s because five decades have passed, or because Robbie wound up reconciling with his wife shortly thereafter, but there’s an almost comical disconnect between Robertson’s laid-back, groovy recollections and what a tumultuous time his roommate is clearly having. The disastrous receptions of New York, New York and the director’s ill-fated Broadway musical The Act are mentioned only in passing.

We get little hints of the darkness roiling beneath, like a Scorsese chasing “a brunette I did not know” down the driveway wearing only his pajama tops, or Marty and his then-lover Liza Minnelli destroying a hotel room during a spat. Roberston describes a wine bottle they’d smashed against the ceiling leaving red liquid dripping from the chandelier like “something out of Visconti.” The detail that sticks with me most is Scorsese trying to pay at a restaurant with bills stained with blood because they’d been up his nose the night before. At one point, a doctor tells them to stop doing so much coke because it’s bad for the septum, and suggests using methamphetamines instead, like he does. (“’70s medicine,” Roberston muses.)

Special guest stars abound, like the avuncular Francis Ford Coppola, who jerry-rigs one of Scorsese’s 16mm projectors to stir the spaghetti sauce he’s been cooking while they all go out to a screening of The Last Waltz. Later he’ll hire a personal chef for the boys, as their extracurricular activities have left them looking a little emaciated in his eyes. Insomnia takes place in a party-hopping Hollywood where you can say goodnight to Jack Nicholson at one gathering, then when you arrive at your next destination find he’s already there. (If anyone could be at multiple parties at once, it’s Jack.) The author diagnoses his own prodigious womanizing as something of a bad habit, but surmises “It can’t be worse for me than smoking cigarettes.” Roberston puts up some pretty impressive stats during the book, but one of the comic highlights is how badly he strikes out with Sophia Loren.

The party finally ended when Scorsese nearly died, hemorrhaging so much that blood was reportedly gushing from every orifice in his head, though Roberston characteristically sidesteps such gory details. The director would eventually recover and turn this long, dark night of the soul into Raging Bull, while the two friends continued to collaborate on soundtracks up through 2023’s Killers of the Flower Moon, though always going home to separate residences. Of visiting Scorsese in the hospital, Roberston writes, “I knew then, looking into Marty’s eyes, that the safest place for me was at home with my wife and kids. And the safest place for Marty was not living with me.”

“Insomnia” is on bookshelves now.