There really was a Grammy Hall. The “classic Jew-hater” of Woody Allen’s 1977 Best Picture-winner Annie Hall was inspired – in name only, we hope – by the grandmother of the movie’s star, Diane Keaton, born Diane Hall in 1946. The titular role was written specifically for Allen’s frequent co-star and former lover, designed to incorporate Keaton’s unique fashion sense and loopy turns of phrase. Unlike Annie, though, Keaton did not hail from Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin but rather Orange County, California, a place that might as well have been rural Mississippi to the famously New York City-centric filmmaker. In a recent remembrance, Allen wrote the first time he met her he thought, “If Huckleberry Finn was a gorgeous young woman, he’d be Keaton.”

The greatness of Annie Hall is almost too imposing for a column like this. The Citizen Kane of romantic comedies, it’s a swaggering feat of innovation that busted open the parameters of what movies like this could do. All the off-the-wall experimentation of Allen’s earlier slapstick comedies is present and accounted for, but in the service of characters we care deeply about, with emotions grounded in a recognizable reality much like our own. As with Citizen Kane, it’s a movie I’ve seen countless times yet the structure is so freewheeling I’m never sure exactly which scene is coming next. It’s a film where adult characters wander freely through flashbacks to their childhoods and Marshall McLuhan is on hand to referee movie-line disputes. I always forget about the animated interlude during which a cartoon Woody Allen is dating the Wicked Queen from Snow White, grousing that she must be having her period.

The picture was billed as “a nervous romance,” but initially Annie was only to be a supporting character. Anhedonia was Allen’s original title: a clinical diagnosis of our protagonist’s inability to enjoy anything. (Accurate, if not exactly marquee friendly. Co-writer Marshall Brickman suggested the alternative It Had to Be Jew.) Allen plays Alvy Singer, a twice-divorced, Brooklyn-born standup comedian and neurotic basket case whose biography lines up closely with the filmmaker’s own. He’s the prototypical Woody character, slouching in an army surplus jacket and muttering devastating one-liners as he self-sabotages every good thing in his life. Alvy explains away his inability to let himself be loved with the old Groucho Marx joke, “I wouldn’t want to belong to any club that would have someone like me as a member.”

The first cut of the film ran nearly two-and-a-half hours, and included a whodunit plot that the director would wisely scrap and revisit with Keaton in their eighth and final film together, 1992’s Manhattan Murder Mystery. Allen, Brickman and editor Ralph Rosenblum realized Anhedonia wasn’t working. What did work were the scenes with Annie, so they radically restructured the movie around Alvy and Annie’s relationship in the cutting room. Allen’s wistful closing voice-over with the “but we need the eggs” stinger was reportedly recorded two hours before a test screening.

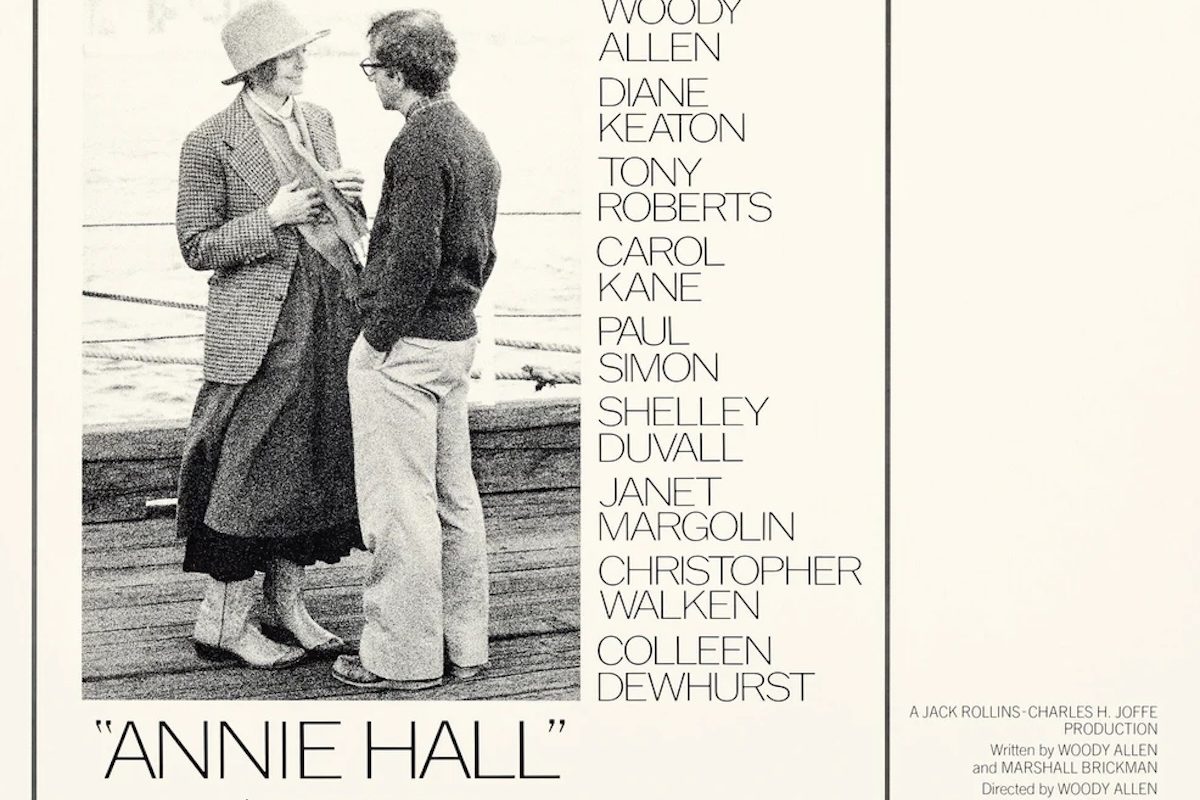

Keaton is so incandescent in the film, re-orienting the entire movie around her seems like simple common sense. An instant icon in her men’s ties and wide-brimmed hats, Annie’s a gregarious oddball with a contagious cackle and a penchant for nonsense phrases like her immortal “Lah-di-dah.” Allen’s Alvy is perpetually disgruntled, always agitated and in the midst of rolling his eyes. He speaks in a string of witheringly funny put-downs. But Annie’s exuberance breaks through his protective armor of cynicism. When she’s around, you can see Alvy loosening up and allowing himself to actually enjoy things… he almost even has a little fun.

Keaton gives us a character in the process of discovering herself. Alvy jokes about her black soap and adult education classes, but we can see Annie is an explorer. The gift of Keaton’s performance – which is even more remarkable given the film’s non-chronological structure – is how she allows us to observe Annie growing into herself. Spot the difference in her confidence during the two scenes in which we see her singing. Annie is in the process of finding her own path, and it’s one that won’t include Alvy. Like so many of Allen’s protagonists, he’s so set in his ways that the picture can only end with him alone and aloof. (People joke about all the great-looking women Allen manages to land in his movies, but few note how seldom he winds up with them in the end.)

An unfortunate side effect of the filmmaker falling out of fashion in recent years is that Rob Reiner and Nora Ephron’s When Harry Met Sally… appears to have eclipsed Annie Hall in the popular rom-com pantheon. It’s a perfectly fine picture, but even when I first saw it in the theater at age 14, I was put off by how shamelessly derivative it is. (I remember the late, lamented Premiere magazine published a helpful two-page chart listing all the key scenes in When Harry Met Sally… and the corresponding scenes in Annie Hall and Manhattan from which they were lifted.) Besides, I always thought it was a little bit of a bummer that Harry and Sally are given a conventional, happily-ever-after ending, whereas Annie Hall is doing something more sophisticated and grown-up, acknowledging how certain relationships can shape our lives and mean a lot without being meant to last.

“Annie Hall” is streaming on MGM+ and Hoopla.