Have you heard? There’s a new trend sweeping the nation’s youth: abstinence. According to recent studies, America’s young people are having less sex than ever before, or at least since we began keeping track of such things. The reasons why have been widely speculated on – the twin specters of social media and porn means many adolescents are exposed to sexual content long before they start engaging in it. Compounded by the lingering effects of the pandemic and a reported increase in feelings of anxiety and loneliness, perhaps a “sex recession” isn’t so surprising. Regardless, it seems no matter what the kids are doing, their elders are wringing their hands over it. This latest turn, though, might come as a shock to the two lead characters of Elia Kazan’s 1961 melodrama Splendor in the Grass.

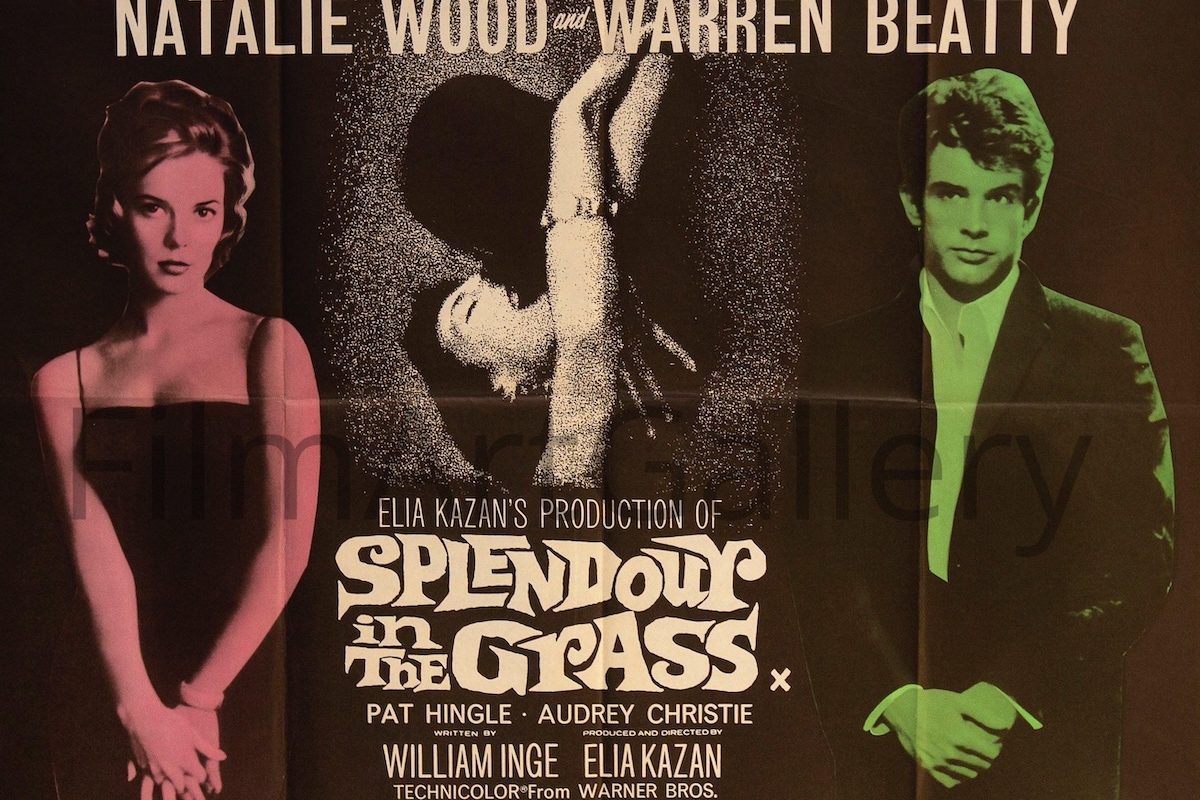

The film opens with a floridly suggestive visual metaphor: as high school sweethearts Bud (Warren Beatty, in his screen debut) and Deanie (Natalie Wood) grapple in a backseat, a waterfall gushes in the background. Set in rural Kansas in 1928, playwright William Inge’s script takes its time to introduce the main players and the social milieu they’re ensnared in. It’s a classic set up: Bud comes from wealth while Deanie is poor. He’s a football star with an overbearing father who wants him to go to Yale in the fall. Her mother is deeply concerned about her daughter getting a reputation in town. “Boys don’t respect a girl they can go all the way with,” she counsels Deanie after Bud has brought her home late. The message to both is clear, if shrouded in coded language: don’t let things go too far or it will ruin their futures.

Their friends and neighbors offer little respite from such harsh judgement. In class, Deanie whispers back and forth with her girlfriends about the dubious purity of a peer. In the locker room after a game, Bud is surrounded by boys jovially boasting about the girls who “know what it’s all about.” When Bud and Deanie are together, they must be mindful of the prying eyes of older bystanders, who seem to simultaneously envy and condemn them.

And then there’s Bud’s sister Ginny (an electric Barbara Loden), who has recently been brought home following a disastrous stint in Chicago; her presence in the film’s first half will linger like a dark cloud over the second. Ginny is “spoiled” in more ways than one. After getting kicked out of school, she was briefly married though her father engineered an annulment. The town gossips whisper about her being in the family way and having “an awful operation.” In contrast to the grimly dutiful Bud, Ginny is defiant in the face of local hypocrisy, leaning all the way into the low expectations that people have for her, dressing in the flapper style and openly consorting with men. “One of these days you’ll find out and then God help you,” she tells Bud after he tries to keep her from a rendez-vous with a married bootlegger. In a scene set on New Year’s Eve that serves as the film’s inflection point, Bud rescues Ginny from an attempted assault. The trauma causes him to break things off with Deanie, spurring them on their separate paths.

Inge’s script and Kazan’s direction work in tandem to establish a hothouse atmosphere that mimics the intense emotions of its teenage protagonists. There’s hardly a moment that doesn’t feel primed to explode. It can be suffocating, if intentionally so, but some critics at the time reacted poorly to what they perceived as the film’s excesses – Brendan Gill of The New Yorker called Splendor “as phony a picture as I can remember seeing.” Bud and Deanie’s parents came in for particular criticism, with Dwight Macdonald of Esquire calling them “stupid to the point of villainy.” But it’s key to the larger points about tradition and inheritance that Inge and Kazan are making that the adults are just as overwrought as their children are.

It’s hopefully not a huge spoiler to reveal that the two kids don’t end up together, but the way that they don’t is both uniquely painful and entirely natural. Following the turn to 1929, the film picks up speed, flashing forward to Bud as he suffers through his first semester at Yale. Meanwhile, Deanie has been institutionalized following a suicide attempt. It’s in these later scenes that Wood’s delicate performance emerges as Splendor’s true soul. Communicating largely through her watchful eyes, Deanie is learning to reconcile her instinctive innocence with the terrible knowledge she’s acquired. “You have to start thinking of your parents as people,” her psychiatrist advises, an instruction that leads directly to the film’s bittersweet final scene.

Two years on from their unrequited love affair, Bud and Deanie are reunited, though their circumstances will keep it from being permanent. “You seem happy,” Deanie says. “I don’t think too much about happiness,” Bud replies. It’s the sort of casually heartbreaking statement about one’s life that’s weighted with decades worth of generational mistakes that have been passed down. “I guess when we get born, we take our chances,” Deanie’s mother observes earlier on, which is another way of saying that we’re often shaped by forces beyond our control. That includes our parents but as Splendor in the Grass makes clear, when we grow up, we become those forces, too.

“Splendor in the Grass” is streaming on the Criterion Channel and Hoopla.