In his two-star review of the 1996 disaster movie Daylight, Roger Ebert had this to say about Sylvester Stallone’s lead performance: “At one point, when a trapped civilian asks [Stallone] if they have a chance, I expected him to say, ‘Calm down, lady. I’ve done this in a dozen other movies.”

By that point in his career, Stallone really had played that part a dozen times, wrapping up a four year run of pure action movies that started with 1993’s Cliffhanger and included Demolition Man (1993), The Specialist (1994), Judge Dredd (1995), Assassins (1995), culminating with Daylight. The coolness, ruthlessness, and invincibility of such roles was a far cry from the vulnerable palooka audiences once cheered on in Rocky.

Enter 1997’s Cop Land, the second feature of writer-director James Mangold. The crime film/modern-day western wouldn’t just tap into Stallone’s vulnerability, reminding audiences of the actor underneath the movie star. It put his vulnerability front and center, resulting in one of the most subtle and honest performances of Stallone’s career.

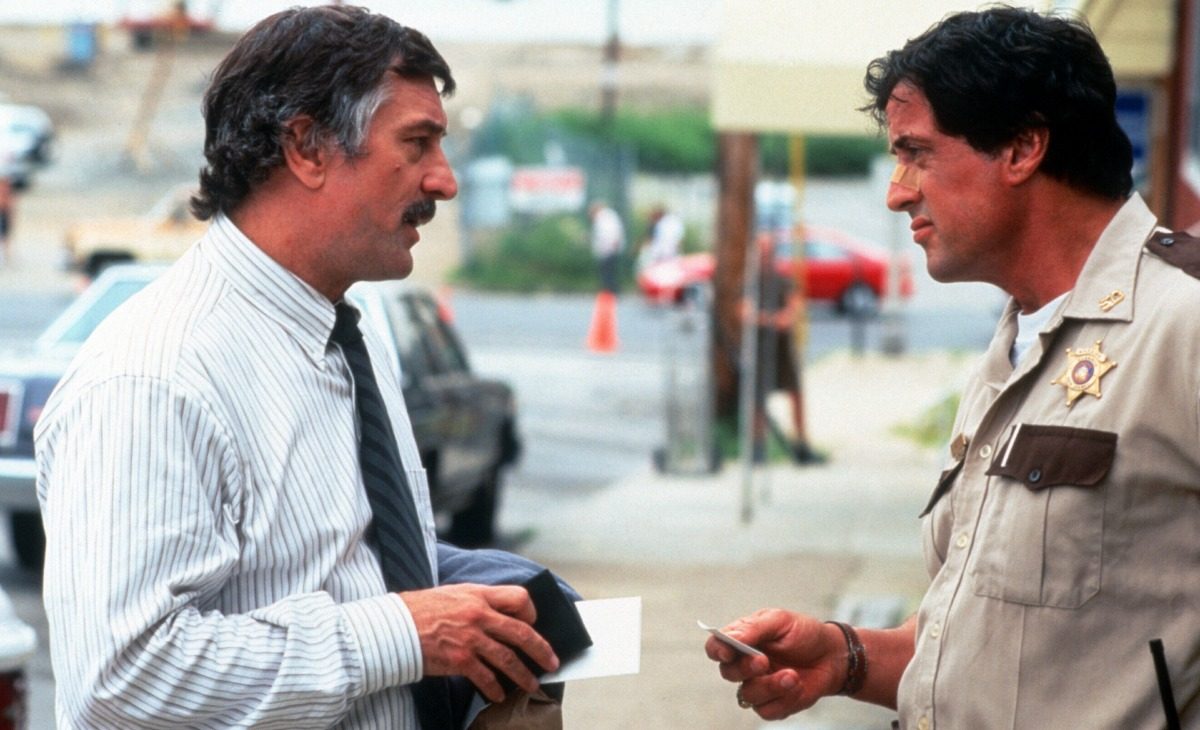

Stallone plays Sheriff Freddy Heflin, the meek, overweight protector of the suburban Garrison, New Jersey, situated right across the Hudson River from New York City. Freddy dreams of being a big city cop, but his dream is dashed due to hearing loss in one ear. Rubbing salt in the wound, Garrison is home to several cops from the city, most notably Harvey Keitel’s Ray Donlan. Freddy drinks in the same hole-in-the-wall establishment as these cops, but there’s always a divide, Ray holding court in the backroom while Freddy perches on a stool by the bar out front. The story takes a turn when an NYPD internal affairs investigator (Robert De Niro) arrives in town and opens Freddy’s eyes to the corruption around him.

Around the two-thirds mark, Freddy travels to the city to meet with De Niro’s character. The camera follows behind Stallone as he climbs the stairs of a subway station, the shot reminiscent of a fighter walking to the ring. Suddenly, Freddy emerges onto the street and the camera pulls back. The buildings tower above him and New Yorkers rush past as Freddy, out of his element, looks down at a slip of paper and tries to get his bearings. For maybe the first time in any Stallone movie, he suddenly looks very small.

“I had to give up all my armor,” Stallone said about his performance in a 2010 interview with GQ. Prior to Cop Land’s release, for nearly two decades, Stallone’s physicality had been his shield on screen, a distraction from the sadness in his eyes. In Cop Land, Stallone’s performance is still physical, but instead of the camera cutting to his biceps or pecs, it stays on his face, giving him nowhere to hide.

In one scene, Freddy, who is single and lives alone, is visited by Liz (Annabella Sciorra). When they were teenagers, Freddy rescued Liz from a car accident, the cause of his hearing loss. In the present, Liz is married to Joey (Peter Berg), another cop. After an argument with her husband, she shows up at Freddy’s door. The two end up sitting in his house, listening to Bruce Springsteen’s “Stolen Car” on vinyl. Liz asks Freddy why he never married; Mangold stays close to Stallone’s face. He hesitates to answer. His eyes look down and to the side, can’t look at Liz directly as he says, with a sheepish smile, “All the best girls were taken.” In this moment, Freddy’s vulnerability—and, for that matter, Stallone’s—is palpable. It feels real because, for Stallone, it is real.

Stallone wasn’t supposed to be a movie star. Sly, the recent Netflix documentary about his life, makes that clear. He was typecast as thugs and the only way to break out was to write the parts he wanted. His mouth was crooked and he talked funny. How could someone like that compete with the Keitels and De Niros of the world?

And yet, in Cop Land, Stallone goes toe-to-toe with both actors. It’s hard to separate out how much of his performance is the character and how much of it is Stallone. Maybe that’s the mark of a great performance. So much of Stallone is in Freddy—doubt, frustration, sadness—that it’s hard to imagine anyone else in the role.

“You butt heads with these friends of ours, you’re going to come at them head-on?” Ray Liotta’s Figgis, Freddy’s best friend, admonishes him in the film. “No. You move diagonal. You jag.”Cop Land can be seen as a departure for Stallone, but it can also be seen as a reckoning, an extension of everything he did up until that point. To see it that way, Stallone’s prior work wasn’t an underselling of his talents. Rather, it was avoidance, diagonal moves in relation to his past and traumas. Like a boxer in the ring, he ducked and weaved, maintaining a level of cool despite estrangement from his father, failed romances, and more than a few box-office bombs. With Cop Land, he stopped playing games. He laced up his gloves and faced his demons head-on.

“Cop Land” is streaming on Netflix