For Valentine’s Day, we’re once again looking at the wide variety of onscreen relationships: movies about ill-fated couplings, toxic partners, and unconventional romances, to help offset the sticky-sweetness of the season. Follow along here.

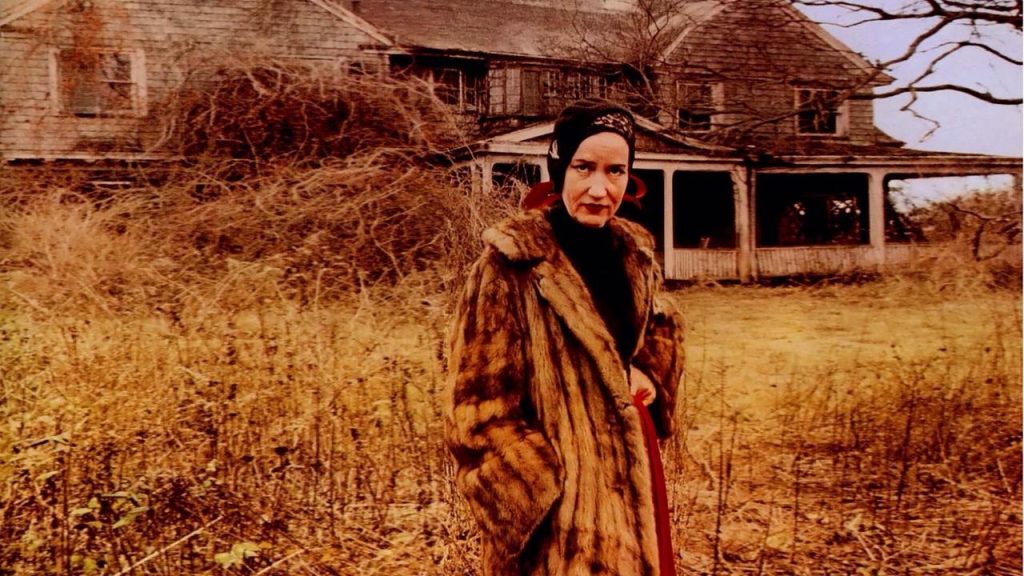

“Kind of a weird romantic comedy” is how writer-director Joan Micklin Silver has referred to her 1979 masterpiece Chilly Scenes of Winter, which for those who have seen it might feel like an understatement. “Weird” doesn’t even begin to describe how antithetical it can feel to the very idea of romance. Many of the tropes that the film mercilessly deconstructs – the guy who won’t take no for an answer, the manic pixie dream girl – were still years, even decades, away from entering the mainstream consciousness. If it was to come out today, phrases like “love bombing” and “toxic masculinity” would likely dominate the reaction on social media. Silver made her film in a different era, but the ways it speaks to our current culture are eerily prescient. Winter is so ahead of its time that we’re still inventing the language to describe it.

This makes sense, though, since central character Charles (John Heard) is very good at articulating his feelings, but very bad at understanding them, or respecting those of others. When we meet him, he’s still nursing the wounds of his breakup with Laura (Mary Beth Hurt), his married-but-separated coworker who has recently returned to her husband. Charles is a civil service employee in Salt Lake City with a best friend Sam (Peter Riegert) and a mentally ill mother (Gloria Grahame) who Charles has to keep fishing out of the bath when she threatens to commit suicide. Otherwise his life is mostly consumed with memories of a two-month relationship that ended almost a year ago.

That’s about the extent of Winter’s plot, but the simplicity of its story belies the intricacy of its construction. Silver’s script hops back and forth in time, spurred by Charles’s brooding and his increasingly alarming behavior as he shifts between relating his tale in voiceover and direct address to the camera. We only ever see moments from his relationship with Laura from his perspective, though it wouldn’t be quite right to call Charles’s narration unreliable; instead Silver uses canny editing to undercut his flights of fancy, constantly denying him the resolution he so desperately seeks from Laura.

Yet Charles isn’t simply an obsessive stalker, nor is Laura merely a daffy beauty. Instead Silver allows both to inhabit a more hazy gray area of uncertainty, even unlikability. Charles is charming but he’s also pushy: on their first date, he asks Laura to move in with him after seeing her spartan apartment, and it’s not entirely a joke. Laura isn’t necessarily encouraging of his behavior, but she does welcome it to a certain extent, a symptom, perhaps, of her husband’s neglect. “If you think I’m that great there must be something wrong with you,” she says to Charles at one point. They share a capriciousness that can make them cruel. In the midst of a fight, he threatens to “beat the shit” out of her. When she eventually goes back to her ex, she says it’s because he makes her feel like “less of a fraud.” All of this unfolds in a realistically dreary winter that seems like it will never thaw out.

Ironically for a film that’s all about the hazards of not letting go, Chilly Scenes of Winter only exists in its current form because of the tenacity of its three producers Amy Robinson, Mark Metcalf, and Griffin Dunne, who bought the rights to the source novel directly from its author, Ann Beattie, and were deeply invested in seeing it succeed. When it was originally released, it was under the much more generic title Head Over Heels, with a much more generic happy ending for Charles and one that Silver was never especially thrilled with. Possibly she felt pressured to meet audience expectations – this was her first studio project after two independently produced features. In any case, by the time of its re-release in 1982, the more downbeat ending, while less true to the book, resonated more with viewers who, like the characters themselves, were a bit too young to attend Woodstock but were made old by the ravages of Vietnam and Watergate.

Silver isn’t a peer to her characters, but she feels an affinity and tenderness for them, even when they’re at their worst. “I can’t think of another generation that was so important when it was so young,” she has said. It’s this spiritual kinship that lends Winter its undercurrent of melancholy – a sense that life doesn’t always work out how we want, but it still goes on. Charles says as much late in the film: “It’s not that it doesn’t still hurt. It’s that you get used to it.” At the dawn of the Reagan era, many of Silver’s cohorts were mourning the dreams of the 60’s that never came to pass. It’s also what should give Winter such legibility with viewers my age, who were in high school during the Iraq War and graduated college in a major recession, and continue connecting it with audiences in the coming years through whatever crises they might bring. That people are disappointing is not the most hopeful message but, as Charles learns, sometimes we’re helped most by what we don’t want to hear.

“Chilly Scenes of Winter” is available on Blu-ray from the Criterion Collection.