It’s a tale as old as time. Boy and girl meet. They fall in love. Marriage and children follow. Then the years pass. Things change. Soon their affections curdle into irritations. Eventually they’re sliding into loathing and disgust. Divorce is threatened. A home is broken. Such is the basic plot of Danny DeVito’s wicked 1989 satire, The War of the Roses, which is about to get a shiny new remake. Maybe there’s still some meat on the bones of such a familiar story – certainly the ways coupling has and hasn’t changed in the years since is ripe material – but it’s hard to imagine a studio picture made today that would dare to be as gleefully rancid a portrait of modern matrimony as the original. Even a film about actual married assassins plays things pretty tame in comparison.

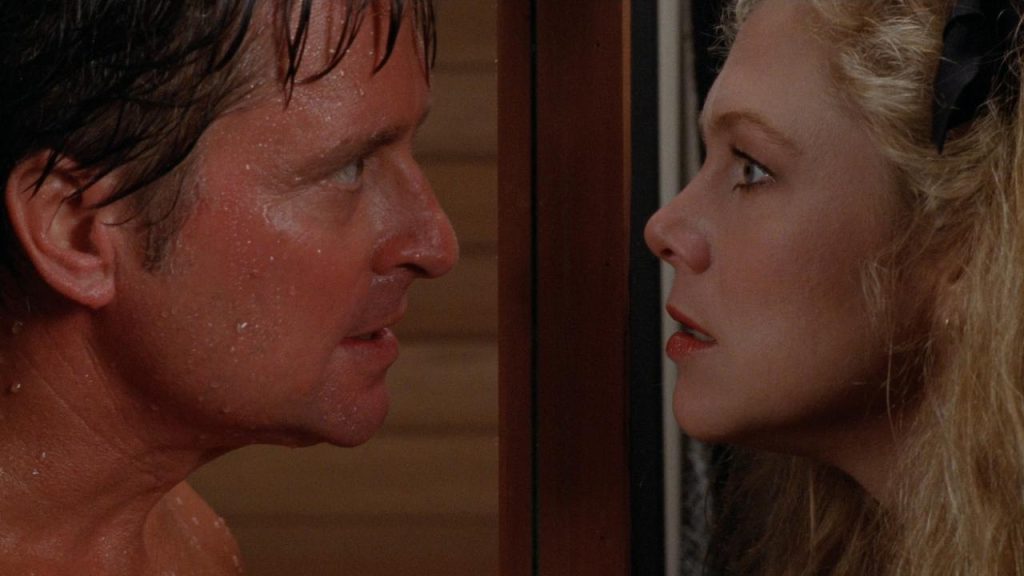

In a canny casting move surely meant to draw in unsuspecting nostalgic viewers, Romancing the Stone stars Michael Douglas and Kathleen Turner reunite as the titular couple, Oliver and Barbara Rose. It’s not quite right to say it’s their story, though. Instead they’re the subjects of a speech delivered by divorce lawyer Gavin D’Amato (DeVito himself) to a potential client. It’s a lesson of sorts, or maybe a warning. There will be no winning here, Gavin proclaims, only “degrees of losing.”

The union seems happy, or at least passionate, for a time. Their meeting has all the makings of a classic rom-com but the groundwork for their later battles is already being laid: at a Nantucket auction, they get into a bidding war over the same lot. Barbara prevails, for now. That initial tension remains present throughout their marriage, even in the ostensibly joyful moments. As Gavin moves swiftly past their early struggles – when Oliver is suffering through law school while Barbara raises their twins – and into the flush years once Oliver makes partner and they’re able to buy an opulent home, the resentments pile up with such efficiency that a blow-up begins to seem not just inevitable but imperative.

Petty cruelties – Barbara sniping about Oliver’s phoniness after a company event; Oliver needling Barbara about spending “his” money – escalate into outright hostility after Oliver has a health scare. In bed that night, Barbara reveals that she imagined his death and the idea made her happy. She asks for a divorce and though he’s reluctant to give it, proceedings begin. True to its Reagan-era time period, the locus of their arguments is the ultimate symbol of American prosperity: the house. Both believe they’re owed it: Oliver because he paid for it, Barbara because she furnished it and raised their children there. On Gavin’s advice, Oliver finds a legal loophole that allows them both to stay in the residence until they settle. And so, the combat truly begins.

What sets The War of the Roses apart from other films of its ilk is the depth of its conviction, and how far it’s willing to go. The physicality that once marked the Roses’ lovemaking is now brutally wielded against one another, and the natural spark between Douglas and Turner becomes weaponized against the audience. Destruction of property (“not the Staffordshires” whines Oliver) leads to dinner party sabotage leads to a gnarly groin injury. Even the house pets aren’t safe from their wrath. Also caught in the crossfire are their embittered children, about to go off to college, and a sweet live-in maid. Once these figures disappear, there’s nothing standing in the way of the Roses following their hateful feud to its macabre end.

Another aspect that sets Roses apart is the stylistic verve of DeVito’s direction. It wasn’t his first foray into the field – that was The Ratings Game five years before. But there’s a sense that, like the central couple, DeVito is going for broke. Aside from a few exteriors, the majority of the film was conspicuously shot on sets, which DeVito highlights rather than hides. The contemporaneous scenes set in Gavin’s office have a particular staginess, with the camera zooming in as the background behind him goes black as if he’s an actor performing a monologue. Such a heightened tone might seem inconsistent with the golden glow of the Roses’ courtship, but DeVito keeps finding ways to puncture the supposed domestic bliss: low angles create the sensation of the characters looming over each other; split diopters keep them in the same frame but distinctly separated. By the last thirty minutes, we’re trapped with the Roses in the blue filter of an endless night.

Like the source novel by Warren Adler, the adaptation’s title references the clashes between the York and Lancaster houses for the English throne in the Middle Ages. In the years since the film’s release, “war of the roses” has become a media shorthand for acrimonious separations. Such ubiquity suggests a certain conceptual fluidity, and it will be interesting to see how the new version modifies it to contemporary mores. But there’s a distinctly late-’80s feel to how Oliver and Barbara covet their property above all, where success is measured in square footage and chandeliers. It clearly resonated with audiences at the time, finishing thirteenth at the box office that year. Ironically, it might be best to approach this updated take the same way Gavin advises his client to consider his rocky marriage: “Be generous to the point of night sweats.”

“The War of the Roses” is available for digital rental or purchase.