Throughout his incredible career, Hideaki Anno has run the gamut from pervasive nihilism to shocking optimism. Possessing a profound ability for self-reflection, the director’s latest, Shin Kamen Rider, continues the trend of his live-action remakes and adaptations of classic stories and characters from his youth. By looking back at his prior, most notable creations, his latest films take on new life. Anno’s latest works showcase an artist able to utilize all of his specific gifts and tools into work that expresses his long-standing capabilities and experience.

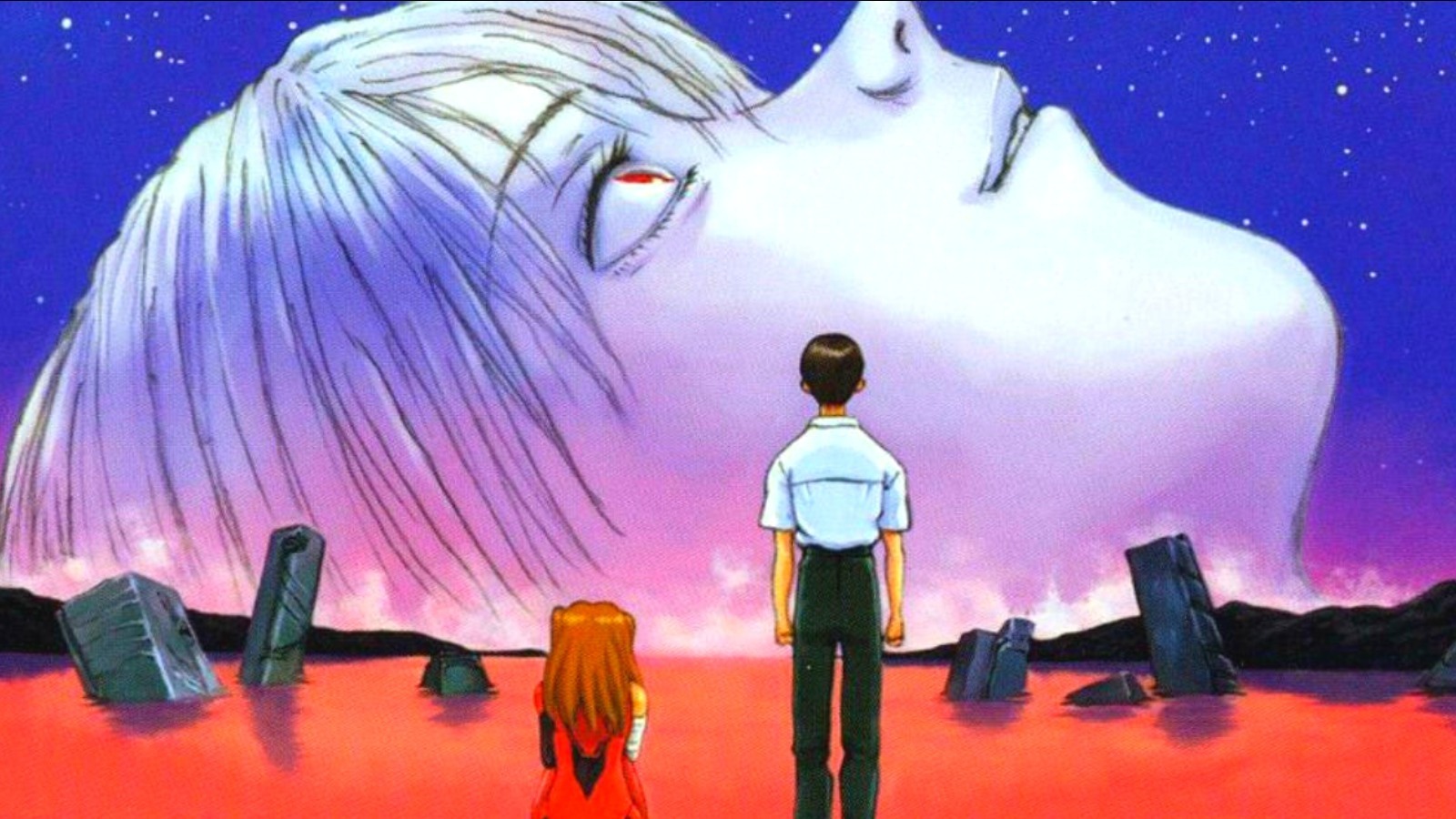

When we think of Anno, a striking set of images first come to mind: A distinctive robotic titan being brutally impaled by a contorted depiction of an angel as a boy looks on, gripping his contorted face in agony. The birth of a new Angel whose body uncurls itself towards the fiery sky. That Angel’s face caved partially in, half submerged in the remnants of a broken world.

Anno’s oeuvre is haunting and limitless, his career a work of opposing structures. Despite the kinetic form the medium can take, his animated works often play with stillness. In Neon Genesis: Evangelion, a series plagued by budgetary conflicts and led by an artist facing a bout of depression, frames are left deliberately blank. Instead of the constant action best associated with classic mecha anime, Anno approaches with a deft hand of patience, instilling the languid, sluggish gait of someone suffering from mental turmoil.

Aside from the archetypal character designs, there’s a distinctiveness to Anno’s work that permeates through all of his work but is most notable in the Evangelion series, from the first season, subsequent film, and then the “Rebuild” series. Depicting Tokyo’s reticular, urban landscape, where physical monsters drop from the sky but the real ones live below, his work is that of someone who understands space.

The stillness in the imagery (alongside the Dadaist stripped-down visuals) works against what we expect not only in the animated medium but cinema in general — especially in mainstream media. This is in part what makes Neon Genesis Evangelion (and all of his work) such an intriguing artistic experiment: by going against conventional expectations.

This style is used most famously in the final two episodes. His abstract approach to depicting the suffering of the archetypal Chosen One, Shinji, caused immense controversy when first released, but in hindsight, it’s a genius approach to what is an apocalypse story. This abstraction is a tool so that viewers must pour over the imagery — or lack thereof — to derive their own meaning. This apocalyptic sense of foreboding doesn’t need to manifest by way of worldwide annihilation; sometimes, the worst version of the end of the world is the one that was imagined in our most vulnerable moments.

In contrast, there’s a playfulness to Anno’s recent trilogy of tokusatsu (the Japanese equivalent of an effects-heavy action film or series) remakes that, at first, is at odds with what we expect from the director. Yet he has never shied away from work that inspires him. From television series such as Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water (based on a concept from Hayao Miyazaki and themes and ideologies drawn from the works of Jules Verne) to the tokusatsu film Cutie Honey ( a 2004 adaptation of one of Go Nagai’s famous manga), Anno has often honored the work that’s come before him. Even Shin Kamen Rider is being released in honor of the 50th anniversary of the original incarnation of the superhero series, which ran from 1971 to 1973.

For all of that stillness, movement is also one of the greatest tools in his arsenal. It’s the dissonance of combining teeth-grinding action with scenes of zero movement and stark voice-over that creates some of his most lasting images: the sinewy muscle that’s torn away from the Eva’s body that aligns with the offputting, irregularity of Godzilla ambling down the streets of Tokyo in Shin Godzilla. The two styles both show off carnage by way of psychological body horror.

The stillness of Anno’s work is used to similar gratifying, grotesque effect, as when Shinji is forced to kill the first person to have ever expressed open-faced kindness towards him. The camera holds onShinji’s Eva for an uncomfortably long time before the decision is made, which leads to the final two episodes and Shinji’s psychological break.

All of this makes The End of Evangelion, the movie which harbored Anno’s most nihilist tendencies, such a natural progression. In his first attempt at remaking his most iconic creation, End is the antithesis to the original series, one that specifically calls out the viewers, the nameless spectators, as they take in all the carnage they’d wanted but weren’t originally given. It’s a relentless, traumatic film, one often likened to David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, another case of a director bringing greater depth and despair to an iconic work in ways even longtime fans couldn’t begin to comprehend.

Anno’s “Rebuild” series — a theatrical retelling of the original show and film — and 2021’s Evangelion 3.0+1: Thrice Upon a Time give viewers the vantage point to witness a director fully remake himself. This is literally put to visuals as Shinji sits on a beach, the ocean waves and sea mist washing away layers of animation until, at one point, he’s no more than a pencil sketch. Through these Rebuild series, Anno demonstrates an artist’s greatest gift, beyond their ability to open doorways to empathy. He’s able to visualize growth and change, tangible signs of how art can depict the herculean ability to heal.

Anno burns the world down at The End of Evangelion. Evangelion 3.0+1.0: Thrice Upon a Time takes a different approach, shouldering the burden of building from the wreckage and the clarity that comes with envisioning what comes after loss. In “Thrice Upon a Time,” Anno takes the wreckage of his art and reconfigures it into something just as potent. The films don’t exist as a rewrite, but to show the filmmaker’s growth through their characters. The result is simply, purely, an evolution of art.

For a director whose work inspires visceral responses (especially for those who’ve watched The End of Evangelion) and whose career can be defined by searing, lasting, imagery, he’s more eclectic than one might expect. Films such as 1998’s Love & Pop and 1998-1999 television series Kare Kano (His and Her Circumstances) exhibit a spirited, playful side. This is true too in earlier episodes of Neon Genesis Evangelion, such as when two characters dance to synchronize in battle.

Shin Ultraman (which he co-wrote but did not direct) and now Shin Kamen Rider express this gleeful storytelling, and remind us that he is a creator of combatant instincts. Hideaki Anno’s greatest magic tricks arrive when he’s able to marry both the inherent darkness of his stories with the optimism that comes from the possibility of something more.