A man wearing an oversized newsboy cap leans against a cinderblock wall, strumming a chord on his guitar while looking at a photographer through hooded eyes. A phone line crackles as a man describes his dream house to a young woman whose face contorts with heartbreak before settling into an expression of joy. A tall, bald man in a khaki jumpsuit recites a soliloquy from The Tempest with fire and brimstone, encouraged by a director to get louder and more passionate. An MC steps behind a microphone and spits verse about his tumultuous upbringing with heartbreak and hope.

In theory, music and arts programs in prisons are a benefit to the incarcerated and to the community. Through the arts, incarcerated people can put the experiences that led them to prisons into perspective and gain catharsis; they can connect with others who have experienced similar problems; they give the incarcerated skills they can apply to their lives when they’re released. How does this play out in practice? Over the past two decades, documentary filmmakers have looked at formal and informal arts programs—how they’re organized, the people who enroll in them, and the effects they have both during the inmates’ sentences and after they’re released. How do these programs play out, both behind bars and in the world outside the prison walls?

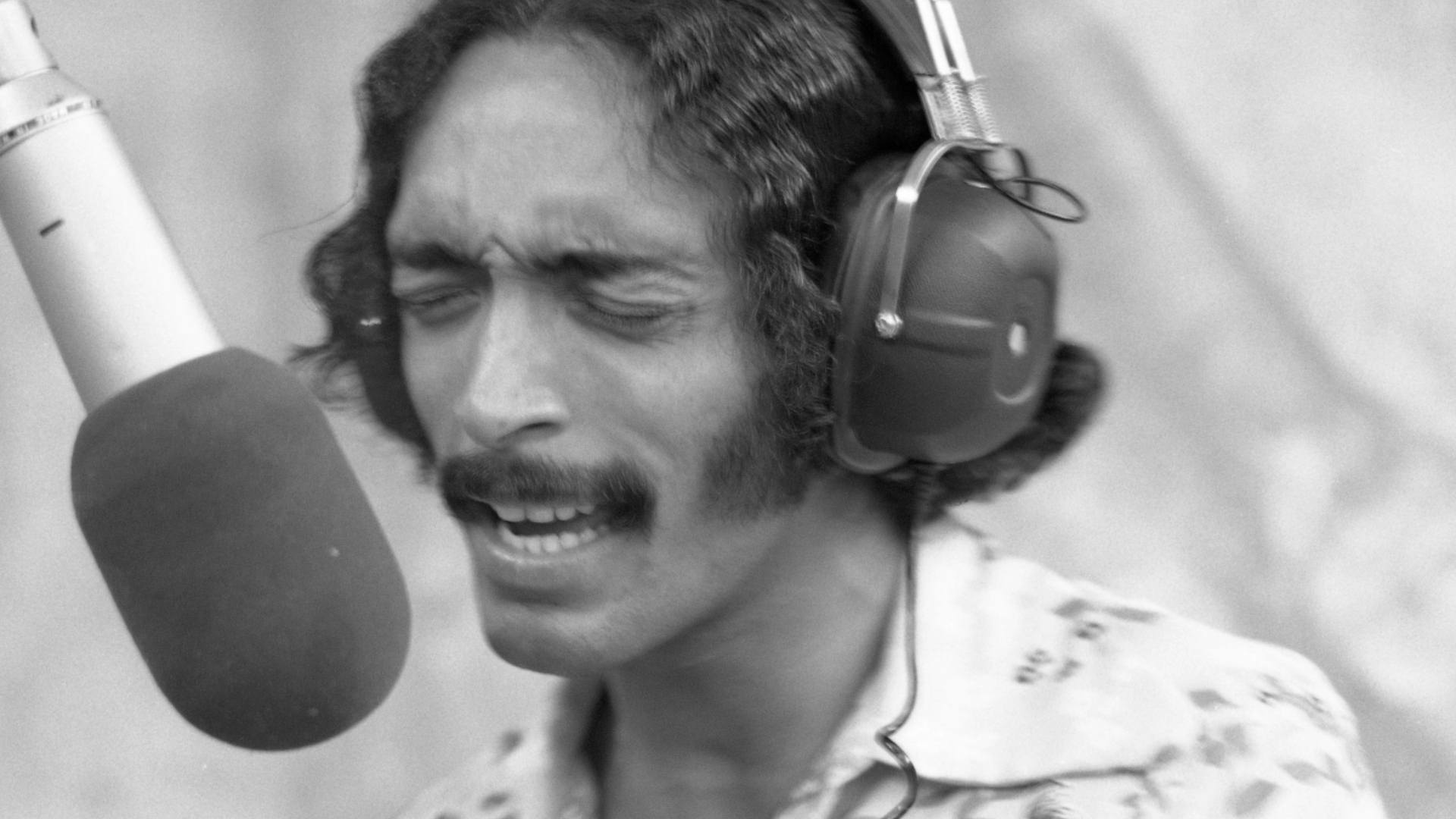

Daniel Vernon’s documentary The Changin’ Times of Ike White depicts one of the earliest prison arts programs. While serving a life sentence for armed robbery, musician Ike White played with the San Quentin Prison Band, where he backed up Eric Burdon of War. Impressed by White’s musical ability and songwriting skills, War producer and LAX Records owner Jerry Goldstein sent a mobile recording unit to the prison to record Changin’ Times, the only record White would release under his own name. The record was a cult hit that especially resonated among musicians, and Stevie Wonder set White up with a lawyer who re-tried his case and got him released.

As one of White’s cellmates observed, “Getting out in a world you don’t know how to operate in and having people have you stereotyped (means) you have to go through life concealing who you really are.” Throughout his life, White changed his name and lied about some parts of his past, marrying and fathering children with several different women and passing himself off as the son of a doting elderly woman. Music and visual art give him a way to express himself and blow off steam, but his violence and boundless sexual appetites frequently caught up with him, so he moved on and changed his identity.

Less than half of Changin’ Times takes place in prison, but the trauma of incarceration reverberates throughout the film. One of White’s wives observes that, because he was sentenced at the age of 17, his personality and his defense mechanisms formed while he was incarcerated, and he was unable to develop healthy ways to deal with conflict in the outside world. San Quentin didn’t seem to have programs that allowed prisoners to adapt to the world after they were released, and while he was a cause celebre among Los Angeles funk musicians and fans, the music world didn’t offer the stability he needed after he was released. The music we hear from his album Changin’ Times was on par with what bands like War and Sly & the Family Stone were releasing, and audiences are left to wonder what White would have made if there were a better way for him to adapt to life after release.

Like Ike White, Herman Wallace was imprisoned in the early 1970s for armed robbery; like White, he entered prison during a politically volatile time for Black men. Unlike his California counterpart, Wallace never had the opportunity to leave prison—or even his cell. After he was found guilty of killing a corrections officer, Herman Wallace became one of the Angola Three, a trio of prisoners that served 40-year sentences in solitary. Artist Jackie Sumell learned of Wallace through an arts class, started writing to him, and began making site-specific art about his incarceration. Herman’s House portrays Sumell’s attempts to make Wallace’s dream house.

While the Changin’ Times filmmakers could draw from a wealth of archival footage, very little media exists of Herman Wallace. His phone calls with Sumell play over montages of her making parts for a mock jail cell that would become a central part of her gallery shows, and a yellowed Polaroid photo of Wallace is tacked to a bulletin board in an interview with his Angola 3 peer Robert King (who had been released at that point). Where Ike White comes off as the protagonist of his own documentary, Herman Wallace seems like a ghost in the film that bears his name. As a result, the film at times seems more like a documentary about Sumell’s art project and less about the Angola 3 or about Wallace’s incarceration.

The most effective scenes in Herman’s House look at the trauma of incarceration for those on the outside. Wallace’s sister appears throughout the film to explain the effect of his absence on her family. In one memorable scene, she and Sumell look at vacant lots in New Orleans to find a place to build the house, vetoing lots that were too close to different traumatic events. Her commentary on the color line and on crime in New Orleans shows the circumstances that can lead to incarceration for marginalized people. As this scene unfolds, Sumell also meets an unidentified Black man who asks her not to relocate Wallace in this neighborhood; when she argues with him about how no one deserves solitary confinement, he replies that “some people deserve it and some don’t.” Because Black people make up a majority of the incarcerated population, white people might assume they’re uniformly in support of prison abolition. Director Anghad Bhalla’s inclusion of this scene reminds the white liberal audience members watching Herman’s House that Black people are not a political or social monolith.

Changin’ Times and Herman’s House both look at informal arts programs for incarcerated individuals with outstanding circumstances. What would more formal arts programs for a general incarcerated population look like? Shakespeare Behind Bars follows a group of men at Luther Luckett Correctional Complex in Kentucky as they stage a production of The Tempest.

After watching the first two documentaries, the sense of place in Shakespeare Behind Bars seemed especially significant. While prison isn’t a place anyone wants to go, director Hank Rogerson neither glamorizes it nor makes it look especially scary. For better or for worse, Luther Luckett is where these characters live, and we see their classrooms, common areas, tiny cells, and mess hall in eye-level shots lit in the dim available light. Against Luther Luckett’s grimy gray background, the backdrops, costumes, and masks of The Tempest seem even more colorful.

Where Changin’ Times and Herman’s House humanized their protagonists by leading with their talents, and focusing on the cruelty of the carceral system towards Black men, Shakespeare Behind Bars takes the opposite approach. The protagonists address the camera directly when talking about the crimes they were convicted of and how they ended up at Luther Luckett, almost daring the audience to dismiss them as irredeemable. As the film progresses, we see their crimes in the larger context of who they are; learning about Hal’s fundamentalist Christian upbringing and internalized homophobia, for example, allows us to understand why he murdered his wife. Rogerson depicts his ensemble’s sexuality in a similarly straightforward, non-sensationalistic way. A rehearsal of a scene between Prospero and Miranda that unintentionally turns flirtatious leads to Hal discussing his sexual orientation, and when Red is commended for getting in touch with his femininity while playing Miranda, he simply shrugs, “Hey, I’m bisexual.”

Because many members of the Shakespeare Behind Bars ensemble are serving life sentences, we don’t get to see how the skills that come with staging a play—like the socialization of working with others to achieve a goal or the sense of structure that can come with the creative process—can help in life outside the razor wire. Because the four protagonists in 16 Bars are serving shorter sentences, this documentary can show how these skills, along with programs offered at the Justice Center, can allow the incarcerated a gradual return to life outside. 16 Bars follows four members of a rehab group at Richmond City Justice Center in Virginia who work on a recording project with Speech Thomas of Arrested Development.

These four men—Teddy Kane, Garland Carr, Devonte James, and Anthony Johnson—open their scenes by discussing their crimes. Unlike their Shakespearean peers, they root these explanations in the context of the desperate circumstances in their lives. Teddy, whose clear-eyed ruminations and pragmatic attitude make him the de facto protagonist, gives the film a mission statement in his opening scene, when he announces, “I feel like if I could change, anybody could.” Throughout the film, we see how hard change can be, both within and outside the prison. As country singer Garland’s notion of justice changes, he opts to plead guilty in his upcoming court case—which would extend his sentence and get him transferred out of the lower-security Justice Center—because he sees it as the right thing to do. Conversely, MC Anthony is removed from the program after he repeatedly picks fights with corrections officers and other inmates.

Because these inmates serve sentences of up to 18 months, the final scenes in 16 Bars show how the Justice Center prepares them for life after release. While social workers at the Justice Center help Devonte find a job and Anthony get a bed at a halfway house, Teddy Kane ends up in an unstable living arrangement and eventually on the street. The program that included the music writing and recording project gave them opportunities to learn new skills and try to find work, but it couldn’t overcome the greater barriers that many of the formerly incarcerated experience.

The audiences for these documentaries may have a mental image of the typical incarcerated person as a large, violent man who deserves to be behind bars, both for his and for our safety. Movies like these humanize the imprisoned because they help viewers understand how they ended up incarcerated and put their imprisonment in a larger social context. Over the past few years, we as a society have started to ask ourselves hard questions about the racial bias baked into the carceral system, as well as the treatment of those within the prisons. Perhaps the next step for organizers of arts programs in prisons and for documentary filmmakers isn’t just to humanize the incarcerated, but to ask themselves—and us—what a world without prisons would look like.

“The Changin’ Times of Ike White” is out Tuesday on DVD and VOD.