The use of animation as a cinematic medium is now as common as going to the local multiplex and seeing a superhero soaring or the umpteenth horror-franchise sequel. Though any given calendar year has months-long gaps wherein families can’t see a new animated film, 2024 alone will have a handful of mainstream animated releases from a fourth Kung Fu Panda to a fourth Despicable Me to a recently announced Moana sequel (Disney’s moving too slow to make it a fourth Moana sequel). But while we live in a world of mainstream animated franchises and intellectual-property cash-grabs, the beginnings of the medium predate even the original Disney animated feature-length film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. 110 years ago, the first true spark of the power of animation on film began through American vaudeville, but naturally, a dinosaur was involved.

Her name, and the name of the short celebrating its 110th anniversary this month, was Gertie the Dinosaur. Though you may have heard of Gertie, from animator and director Winsor McCay, as being the first animated short film, McCay had made two previous shorts earlier in the 1910s, Little Nemo and How a Mosquito Operates. (The latter title depicts a mosquito sucking the blood out of a man, at least making very good on the promise of its name.) Because of the more primitive nature of cinema in the early 1910s, Gertie the Dinosaur cannot be looked at as a pioneering example of high-quality visuals. (For context of how early these days of cinema were, D.W. Griffith’s epic and controversial The Birth of a Nation wouldn’t be released until 1915.) The importance of Gertie is less about eye-popping visuals as displayed in its black-and-white animation style, and more because it serves as one of the most important proofs of concept to ever exist in cinematic technology.

As documented in animation historian John Canemaker’s biography of McCay, the animator himself seemed to perceive Gertie in terms of what technical accomplishments he could achieve, as he tried to expand the detail of backgrounds in the short as well as making sure that Gertie herself seemed like a genuine dinosaur. This meant McCay would attempt to mimic breathing motions so he could animate them, and ensure that any time Gertie stamped with her huge body on the ground, the rocks underneath would sag appropriately onscreen. Unlike animation created even during the era of Snow White, the work that McCay put into Gertie was entirely self-driven, as he had to draw thousands of frames to comprise the eventual short film, utilizing a technique dubbed the “McCay Split System” wherein characters’ major positions were drawn first and then the in-between styles placed afterwards. Canemaker’s biography captured McCay’s personality in regards to this exhaustive and tedious work (if not animation as a whole) later on; after the film’s release, McCay chose not to be overprotective of his methods, reportedly saying, “Any idiot that wants to make a couple of thousand drawings for a hundred feet of film is welcome to join the club.”

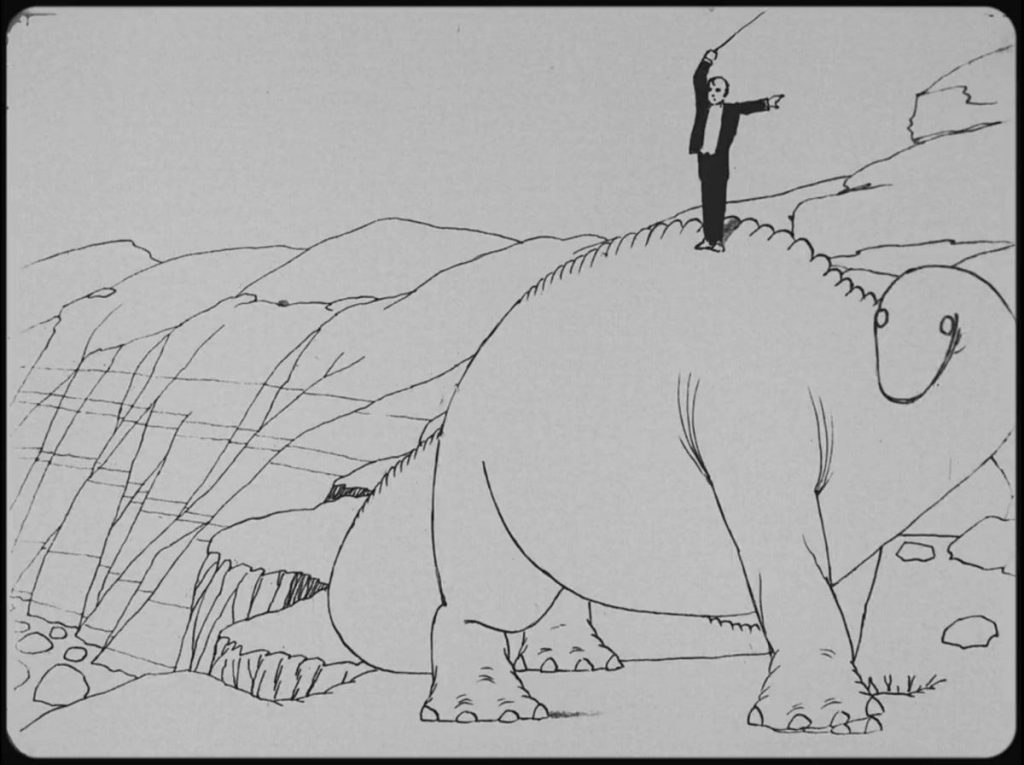

McCay was as much an attraction in selling the film, since the marketing for Gertie the Dinosaur leaned on his presence while also acknowledging that audiences could watch a walking, breathing animated dinosaur. His call-and-response act, as he would perform in front of audiences to show Gertie off like a trained animal, only lasted a few short months. McCay’s primary job was as a political cartoonist for a New York newspaper owned by William Randolph Hearst, famously not the best friend of the working man. Hearst began to crack down on his journalists’ side gigs, so McCay filmed a prologue in which he entertains a group of fellow artists and introduces Gertie like his trained pet; that short lives on today. On one hand, it’s a far cry from the blending of live-action and animation that you can find in everything from Who Framed Roger Rabbit to Space Jam. On the other, it’s equally easy to understand how and why an impresario like Walt Disney would watch Gertie the Dinosaur and exit with immense inspiration.

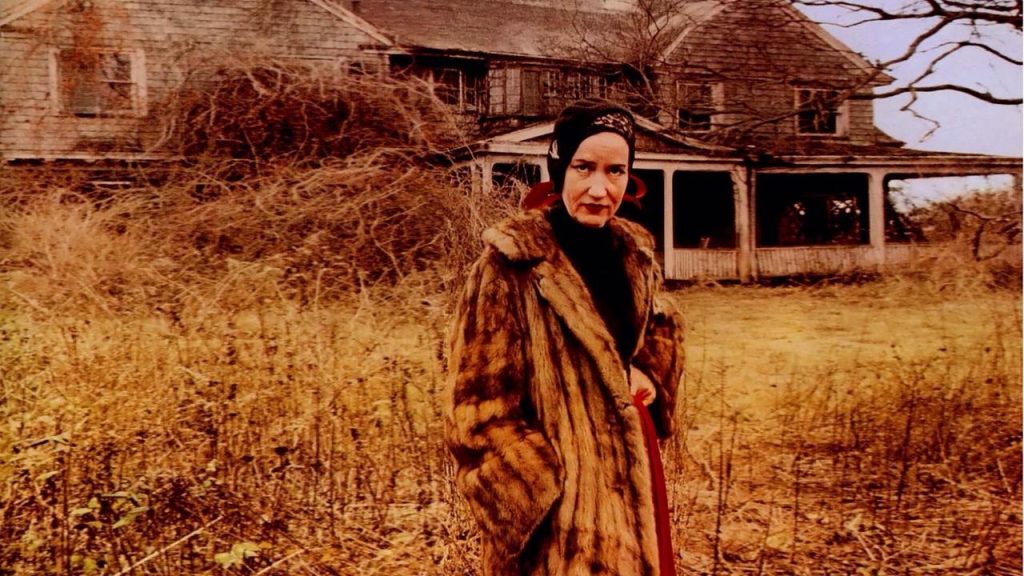

Disney, to his credit, was not shy about noting the debt that he owed to Winsor McCay. Theme-park nerds are no doubt aware that Gertie the Dinosaur is memorialized at Disney’s Hollywood Studios at the Walt Disney World Resort, in the form of an ice-cream stand that is designed to look like Gertie herself. But Disney also helped bring Gertie the Dinosaur to a larger audience in the 1950s, years after many of McCay’s original drawings were ruined in a house fire. Disney worked with McCay’s son Robert to recreate the vaudeville act with Gertie on an early episode of the Disneyland anthology series.

Disney fanatics like to pull out an old quote of Walt’s – that “it all started with a mouse” – to emphasize the genuinely humble beginnings of what is now a corporate behemoth. Even if you forget that Oswald the Lucky Rabbit predated Mickey Mouse, the humble beginnings of Disney the man and Disney the company, and of the current course of animation as a whole, do truly predate these characters. Animation did start with a creature, and it did have much more humble beginnings than its omnipresence in cinematic sequel after sequel. It started with a dinosaur, and Gertie and her master Winsor McCay deserve the recognition more than a century later.