“Sometimes you wanna go where everybody knows your name / And they’re always glad you came…” — Theme from Cheers, Gary Portnoy

Other than bars and bowling alleys, there historically haven’t been that many public places where people can congregate, relax, and forget their worries without having to take out a second mortgage or risk injury. Both spaces appeal to one’s desire to, in Portnoy’s words, not only “be where you can see our troubles are all the same,” but where “people are all the same.” While Cheers and plenty of other TV shows and films excel at presenting bar culture, it wasn’t until the late ’90s that a trio of films nailed the appeal of the lanes.

When Bobby and Peter Farrelly’s Kingpin (out this wqeek in a new 4K Ultra HD edition from KL Studio Classics) hit theaters in 1996, it seemed like bowling movies were the next big cinematic trend. Joel and Ethan Coen’s The Big Lebowski and Vincent Gallo’s Buffalo ’66 followed in 1998, premiering three days apart at the Sundance Film Festival, whose attendees must have experienced a touch of bowling fever alongside the usual Sundance Flu.

True to Portnoy’s lyrics, all three films present bowling alleys as refuges for misfits — the rare places where society’s outcasts are viewed as celebrities. That sense of stardom is exaggerated to comical ends in Kingpin when Roy Munson (Woody Harrelson), fresh off winning the 1979 Iowa state amateur bowling title, returns to his hometown alley and is given a hero’s welcome. As Roy struts to a lane to the tune of The Trammps’ “Disco Inferno” and flamboyantly tosses a ceremonial strike, it’s clear he’s the kind of guy men want to be and women want to be with.

But it’s a tragically short-lived feeling. After a tragic incident robs him of his ability to bowl and sends him into a 17-year, alcohol-induced spiral, Roy sees a chance to return to the spotlight, managing talented Amish amateur bowler Ishmael Boorg (a wonderfully goofy Randy Quaid). Yet as the two road trip to a million-dollar, winner-take-all tournament in Reno with beautiful hustler Claudia (Vanessa Angel), Roy gets to experience the joys of his heyday in unexpected ways, and the reunion with his community changes his life for the better in textbook sappy/immature Farrelly style.

That sense of belonging is especially important to Buffalo ’66 protagonist Billy Brown (Gallo). Released from prison after a five-year stint for a crime he didn’t commit, he kidnaps tap-dance student Layla (a mesmerizing Christina Ricci) and somehow convinces her to pretend to be his wife when they visit his parents, Jan (Angelica Huston) and Jimmy (Ben Gazzara who, coincidentally enough, is also in Lebowski). It’s a messed up situation, and the more that Gallo reveals about Billy’s traumatic past — via fascinating overlay flashbacks and his folks’ modern-day resentment of his very existence — the clearer it becomes just how awful things are and have been for him.

However, all the pain and sadness disappears when Billy goes bowling. Though he’s been away for a long time, alley employee Sonny (Jan-Michael Vincent) has paid the fees for his locker, inside which awaits Billy’s ball along with his other prized possessions, including a framed newspaper clipping of an article celebrating his youth bowling championship and multiple trophies. Juxtaposing how miserable life is at the Brown house with the joy that Billy experiences seeing his bowling gear, reuniting with Sonny, and getting to roll on his favorite lane, Gallo poignantly suggests that the alley has been Billy’s happy place for a long time.

Only a small percentage of Buffalo ’66 takes place at the bowling alley, but Gallo saturates these minutes with the sports eccentricities (including player superstitions). Due to the all-too-relatable malfunctioning ball return system messing up his rhythm, Billy sees his hot streak come to an abrupt end, but not before Gallo celebrates the game’s rituals of Billy putting on his shoes and wrist support, polishing ball in a see-saw towel, and testing out the holes in the ball.

The Big Lebowski also excels at capturing the sport’s core elements, and after the film’s fairly comprehensive opening title sequence, it’s a wonder bowling didn’t surpass baseball as the national pastime. The Coens employ a wealth of extreme close-ups on score cards, balls, pins, beer, cigarettes, ashtrays, and — most importantly — people throwing strikes and celebrating. Cued to Bob Dylan’s insanely catchy “The Man in Me,” the montage makes everything look extra cool while thoroughly building this world. It’s a place where characters and viewers alike want to be, and it’s a treat to return to it throughout the film.

This opening additionally establishes bowling as a game for everyone. Similar to the diversity that the Kingpin crew encounters on the road, a range of sexes, ages, and ethnicities are represented here, but even more pronounced is the collection of wacky personalities that are drawn to the lanes.

It’s borderline miraculous that the seemingly incompatible The Dude (Jeff Bridges), Walter (John Goodman), and Donny (Steve Buscemi) not only function as a bowling team but, despite plenty of animosity, have a genuine friendship. As with Billy, Roy, and Ishmael, the alley is their sanctuary and a builder of community where chosen families are constructed in the absence of loving given ones. When life outside the lanes turns sour or there’s some unexpected free time, Walter is quick say, “Fuck it. Let’s go bowling,” and nearly without fail, things indeed improve within its walls.

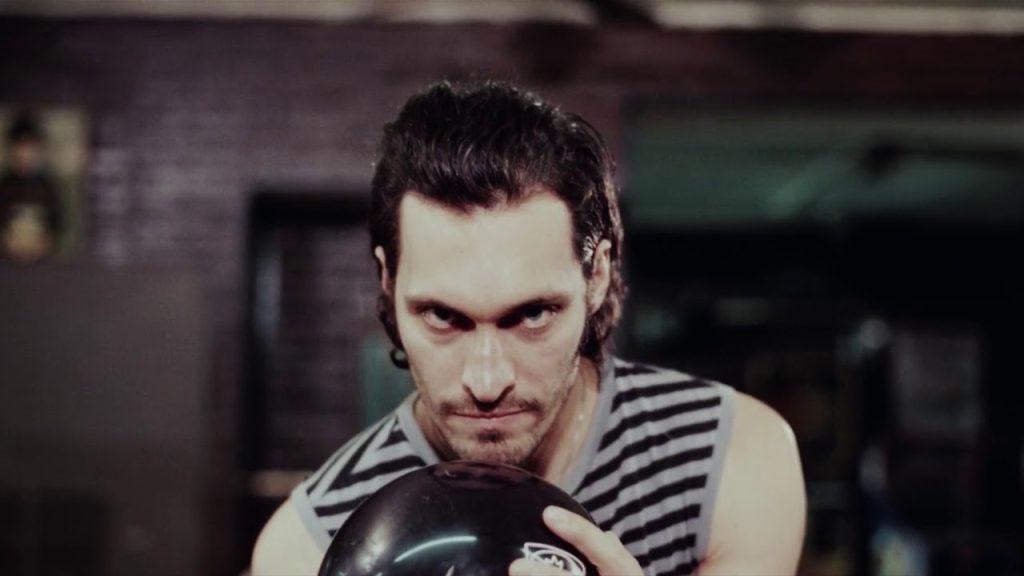

In this place, even a registered sex offender like Jesus (a scene-stealing John Turturro) can be a big shot, respected by our core trio for his skills while his (bowling) ball-licking and general freaky ways keep friendship at a distance. The Coens play up Jesus’s borderline inappropriateness throughout Turturro’s handful of onscreen minutes, most memorably in a hilarious cutaway to Jesus and his teammate Liam (James Hoosier) aggressively waxing their balls at crotch-level see-saws. And the filmmakers double down on the phallic nature of the sport’s equipment via a dream sequence where The Dude imagines himself in an adult film called Gutterballs.

With three excellent and distinct bowling movies released in this two year period, why did the trend suddenly end? Kingpin, The Big Lebowski, and Buffalo ’66 captured the sport’s culture so well and told such engaging stories that perhaps other filmmakers were intimidated to tackle the subject and face inevitable comparisons to one or more of these gems. But a shift in social behavior also may have made subsequent efforts in this niche sub-genre seem less marketable for studios.

Though bowling alleys have endured, the films’ releases coincided with the gradual ubiquity of the internet and the rise in video game systems, both of which encouraged entertainment seekers to stay home. In turn, these three movies arguably captured bowling culture at its peak and/or last gasp, and in the years that followed, the sport seems even more quaint and nostalgic than it did in the late ’90s. When it does appear in movies, it’s usually as a status symbol (e.g. Daniel Plainview’s in-house alley in There Will Be Blood) or to superficially highlight a character’s trait (Lars and the Real Girl) — not to engage with the culture on a deeper level.

“Fuck it,” Walter might say. “Let’s go watch a great bowling movie.”