“These imaginary displays provide a temporary release.” –Kenneth Anger, Fireworks

It’s appropriate that Fireworks, the first short in the late Kenneth Anger’s mystical Magick Lantern Cycle, opens with a recreation of a dream he had when he was 17. He didn’t commit it to celluloid, however, until the spring of 1947, when the then 20-year-old auteur had the run of his family home for an entire weekend while his parents were away. Using the living room as his studio space, Anger and his friends shot the film – including his dream of being held in the arms of a hunky sailor – in 16mm with handmade props and a discarded backdrop from a western movie set. It has the hallmarks of the enthusiastic amateur: many shots are indifferently framed and some are even wildly out of focus. Still, the frank treatment of the subject matter (sadomasochistic, homoerotic desire) and brazen symbolism (got milk, anyone?) marked Anger as a budding talent to watch, one persuasive enough to convince a friend to stick a roman candle in the fly of his pants and light it. That stunt didn’t result in a trip to the emergency room, but if it had, Anger would have gotten it on film – and probably even used the take if the ending of Scorpio Rising is anything to go by.

Born Kenneth Wilbur Anglemeyer, Anger settled on his stage name at an early age (clearly foreseeing what the credit “A Film by Anger” would look like onscreen) and made a handful of short films while in his teens. Some of them were still being screened as late as 1967, when he pulled them from distribution, leaving Fireworks as his earliest in circulation. This remained the case when the nine films in the Magick Lantern Cycle were painstakingly restored and released on DVD by Fantoma Films in 2007. As Anger recounts on the commentary for Fireworks, its Hollywood premiere was attended by such luminaries as James Whale (then in semi-retirement) and Alfred Kinsey, who was in the midst of his research into sexual behavior and immediately approached Anger about buying a print of the film. Fireworks also had such vocal proponents as Tennessee Williams and Jean Cocteau, ensuring the cognoscenti would be paying close attention when he emerged with his next opus.

Anger intended for that to be a feature titled Puce Women, which he fully scripted and storyboarded, but he only shot enough material to make a six-minute short he dubbed Puce Moment. He then accepted an invitation to work at the Cinémathèque Français, and while in Paris was given use of a film studio for four weeks. Quickly building a forest set and concocting a story for three actors from the Marcel Marceau School of Mime to act out, Anger proceeded to shoot what turned out to be his only film in 35mm, but left Rabbit’s Moon unfinished for two decades while he pursued other projects.

His next international stop before returning to Tinseltown was the Garden of the Villa D’Este in Tivoli, Italy, where he made Eaux d’artifice (1953). Strategizing where and when to film to get the backlighting he wanted with natural sunlight, he also needed a midget actress to make the water fountains appear more impressive. None other than Federico Fellini put him in touch with one, so it’s fitting that Anger’s next film was 1954’s The Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, although Fellini himself wouldn’t make such a decadent, colorful film until the following decade.

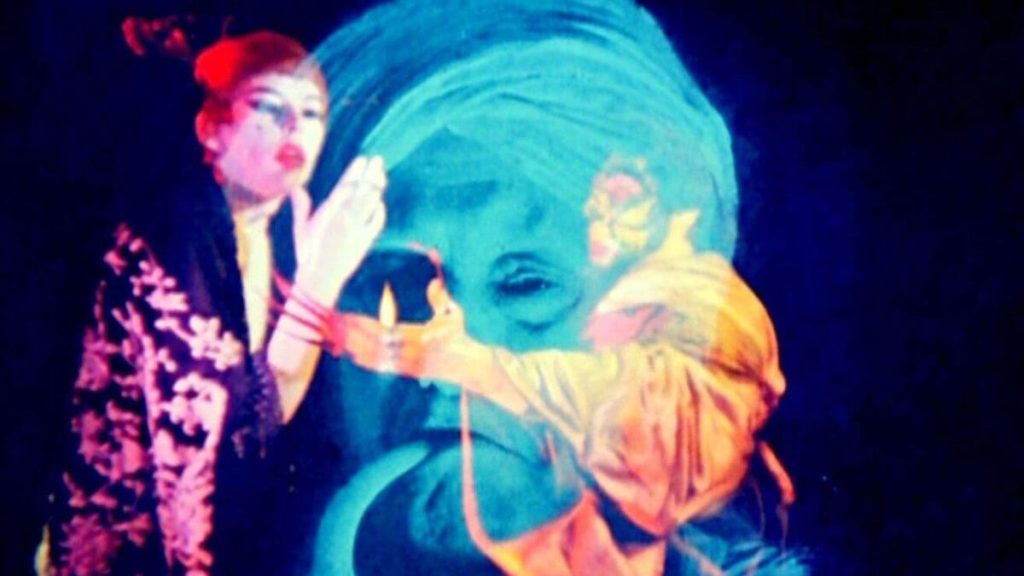

Inspired by a masquerade party Anger attended with the theme “Come as Your Madness,” Inauguration represented his Hollywood homecoming and the culmination of his work up to that point. (It even incorporated footage from Puce Moment.) Drawing on the arcane mythology of Aleister Crowley and incorporating such gods and mythological figures as Isis and Osiris, Aphrodite, Lilith, and Pan, the film is rife with camera tricks, lightning-fast editing, and multiple exposures. That’s on top of the extreme makeup and costumes of the participants, whose ranks include Anaïs Nin (as Astarte, the goddess of the moon) and Anger’s fellow queer underground filmmaker Curtis Harrington (as Cesare the Somnambulist from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari). His longest film to date, it was also the last he completed for close to a decade, although 1959 saw the first publication (in French) of his scandalous book Hollywood Babylon, which wouldn’t be published Stateside until 1965. By then, he had entered his next phase, using popular songs in his films in a way that was his most lasting influence on future filmmakers. (It’s not for nothing that Martin Scorsese penned the introduction for Fantoma’s release.)

Scorpio Rising (1963) grew out of Anger’s contact with a motorcycle club based in Coney Island, and it turned out to be his most death-obsessed film. Shot in a documentary style, Scorpio moves from the garages where members of the club maintain their rides (including one overseen by the Grim Reaper) to a raucous Halloween party where the festivities don’t require much prodding to get out of hand. All the while, Anger overlays the action with songs like “My Boyfriend’s Back,” “He’s a Rebel,” and “I Will Follow Him,” cutting in tinted footage from a religious film delivered to him by mistake. (Another bit of serendipity: The Wild One was playing on TV while he was filming a biker obsessed with Marlon Brando and James Dean.) The brief companion film Kustom Kar Kommandos (1965) similarly gets a great deal of mileage out of its use of “Dream Lover,” but like Puce Moment, it’s a teaser for a longer project that didn’t come to fruition.

The same fate almost befell Lucifer Rising, which Anger tried making in San Francisco in 1967, with Charles Manson associate Bobby Beausoliel as the title character and the participation of Church of Satan founder Anton LaVey. Forced to abandon the project when some of the footage was stolen, Anger fashioned Invocation of My Demon Brother (1969) out of the “leftover scraps” (as he calls them on the commentary), resulting in an understandably disjointed viewing experience, complete with a soundtrack of Mick Jagger screwing around with his brand-new Moog synthesizer while viewing Anger’s haphazard assembly. Fortunately, Anger got another crack at raising Lucifer a few years later, with the biggest budget he ever enjoyed, but first he belatedly completed Rabbit’s Moon, editing the footage he shot in 1950 and adding a soundtrack of doo wop standards including “There’s a Moon Out Tonight,” “I Only Have Eyes for You,” and “Tears on My Pillow.” (He revisited it again in 1979, halving the running time by skipping every other frame and changing the music, making Anger the forerunner of such compulsive tinkerers as Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas, Ridley Scott, and Oliver Stone.)

As for the second coming of Lucifer Rising, it brought back the figures of Isis, Osiris, and Lilith from The Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, sending the actors portraying them (including director Donald Cammell – a fellow Crowley acolyte – and Marianne Faithfull) to such far-flung locales as Egypt, Germany, and the London flat where Anger was staying while its owner was away on business. (Old habits die hard.) When Lucifer Rising received its US premiere in 1974, Film Quarterly reported that it was the first third of Anger’s first feature, but when the other two-thirds failed to materialize, he slapped a 1981 copyright on it and declared his Magick Lantern Cycle complete. And so it remained for the balance of his life.