What we know about the life of Roger Duchesne – actor, gambling addict, failed career criminal, suspected wartime collaborator, figure of demi-monde Montmartre – makes him appear more fiction than fact, more myth than reality. His only enduring screen performance, the title role of Jean-Pierre Melville’s slant, self-conscious meander into noir, Bob le flambeur (1956), lends an intensity to how we might consider the already shadowy nature of Duchesne’s experiences, particularly during and after the Nazi occupation of Paris; and they, in turn, add mystery and thrill to a film defined by Melville’s investment in the mask over the man.

There are undeniable parallels between his life and the one Melville gives Bob, middle-aged former gangster and gambler on the skids drawn to one last heist, parallels which are lent weight by the artifice with which the figure of Bob is constructed. The impression is less of a correspondence between life and art, and more of a ghostly dialogue between fiction and fiction. Melville’s creation of a world that never existed provides the unreal backdrop: his streets of Montmartre and Pigalle are a secluded underworld of gangsters and cops, conjured from an audacious mix of night time location shooting and highly personal, stylised borrowings from a Franco-American blend of cultural sources.

The only depth to Duchesne comes from what we now choose to accord him. A wealth of conflicting stories abounds, with multiple narratives existing for his activities during the war, the reason for his first arrest, and where exactly he was when cast as Bob. However, Duchesne continues to be best known, on a par with Melville’s film, for the rumours of his collaboration with the French Gestapo during the Occupation, his substantial gambling debts to Henri Lafont and other members of SS gangs widely thought to be the catalyst for his involvement.

In retrospect he seems to me, above all else, a man of costume, an impression doubtlessly heightened by watching Bob in which his character is all exteriors, moulded from a collection of cinematic signs. At one moment he enters a bar at dawn to a particularly dramatic musical cue, the Bogartian ensemble of hat, trench, stubble, cigarette and noirish glower all in place. At another, Melville has him in American-inspired tailoring, driving down the autoroute with panache (and no rear projection) in a 1955 Plymouth Belvedere while talking and laughing with a friend, a collagic but coherent ideal of a performance of masculinity achieved through dress and stance – and framed by Melville’s controlled movement between overt stylisation and naturalism.

Duchesne is similarly upholstered. He is not complicated by a star persona forged from his many previous films but always seems disguised, perhaps valuing how clothes make you appropriate to a context and therefore unknowable. As Nick Pinkerton notes in his audio commentary for the film’s 2019 Blu-ray release , it was rumoured Duchesne had attempted to avoid capture during the war by fleeing Paris disguised as a Resistance officer in a suspiciously spotless, home-tailored uniform; and, as per a 1951 article in Le Monde covering his trial for the holdup of a tie merchants’, he spent his share of the robbery on new suits.

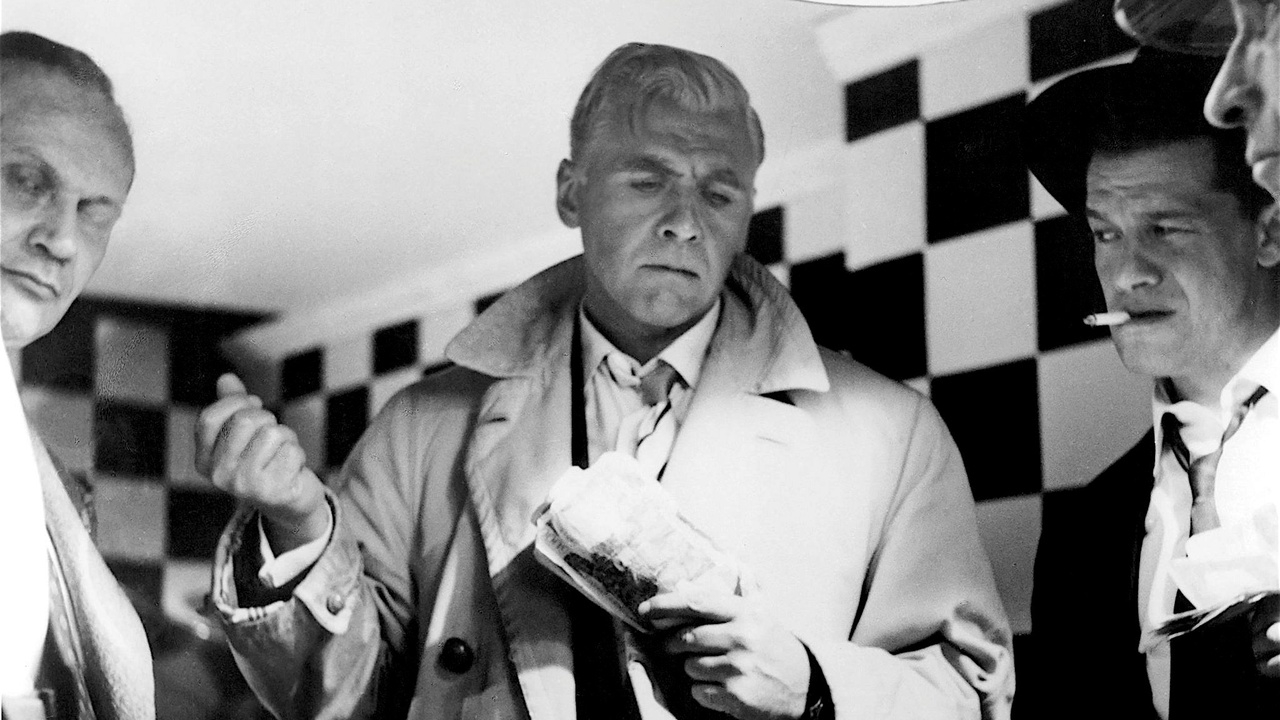

There is also a rather startling photograph taken at one of Duchesne’s many arrests: his exit from the hotel where he had been holed up, wearing a vast, turned-up trench coat under the flare of photographers’ cameras. All that’s visible are the waves of his carefully crenelated hair, the bounds between man and coat appearing to bleed as Duchesne is reduced, or perhaps elevated, to the status of performer in another role. When he was discovered by police, he reportedly told them: “je n’ai pas de chance.” Was Duchesne living in a trashy noir of his own devise, like the ones he spent the forties writing?

During the war, when rumours of his collaborationist sympathies left him a once-popular actor unable to work he became, according to critic Thierry Crifo in the Blu-ray featurette “Diary of a Villain,” the publicist for then-collabo haunt, Pigalle cabaret L’heure bleue; Duchesne led a life that was, as Crifo succinctly puts it, “nocturne et festive.” Fag in hand in almost every shot, heavy-lidded and fat round the middle like the cabbie who makes his living on the night shift, Duchesne wears the cost of an infinite number of evenings we can only imagine. He plays the tired old crook as if he has lived a hard life, full of intensity and fire, at some point in a vanished past that will never be fully visible or accessible to us. It only appears to remain in the marks it has left on the body, that which belongs to actor and role – effecting a symbiosis between the two and grounding Duchesne’s performance, giving it a palpable physicality despite the mythical flavor of the part and the film itself.

Duchesne conveys an intimate pull towards life conjured from artifice, generated by what we can see: a gesture, a way of moving just for a second, drawn from living itself – from the facts of that life and what it required of him, a stance that Imogen Sara Smith describes in an essay on the men of film noir as “minimalist body language speak[ing] of ease painstakingly achieved and sustained.” It is fair to surmise that Duchesne was highly aware of performance as a way of passing muster in the Paris milieu, and this gives his depiction of Bob an odd purity as its crux lies in the image itself, in Melville and Duchesne’s stylised and sometimes faltering construction of it, rather than in set-in-stone biographical correspondence or even cut and dry talent. There remains a creaky, old-fashioned, and awkward aspect to his acting here, but whether he can actually act or not is a question that becomes irrelevant, lost in Melville’s embrace of artifice in every element of Bob and the demands of his scene-making; Duchesne’s ‘self-consciousness’ is put to good use.

His “painstaking” appearance of ease with a certain kind of life can be located in Bob’s performances within the film: the glance given to his hand at the tables, the way he drives his car, dances with young drifter Anne (Isabelle Corey); as well as the rasp to his voice, and the eternal presence of a smoked-down cigarette and how it’s held. And there are those moments which always seem to transpire when an actor (or non-actor, or someone somewhere in between) enacts a role which mirrors their own experiences. Throughout the film, gestures seem to slither tellingly through the cracks: the twitch of his mouth as he consults his deck, the slight shaking of his hand as he rests it above, but not on, Anne’s arm. This was undoubtedly the most accomplished performance of Duchesne’s career.

Duchesne arrives in Bob as if out of a cloud of smoke; his role is an arrival in cinema history, only to be followed by a swift and almost totally consuming departure. He acted in one more film shortly after Bob, with Melville’s appendix, when interviewed by Rui Nogueira in 1971, that “I believe he now sells cars near the Porte de Champerret”; Duchesne’s later years reframed as hearsay, myth. Otherwise, how he lived between 1957 and his death on Christmas Day almost forty years later is still unknown; there’s simply nothing to tell, perhaps.

“Bob le flambeur” is now streaming as part of the “Gamblers” series on the Criterion Channel.