Sometime in early 2016, I was halfway through Polish author Witold Gombrowicz’s last novel Cosmos (1965) — per my edition’s jacket copy, a “metaphysical thriller” about a pair of university students on holiday who discover a dead sparrow hanging by a noose outside of the family-run resort they’re staying at and embark on a surreal investigation — when I put it aside, picked up my phone, and read the announcement that filmmaker and fellow Pole Andrzej Zulawski’s adaptation of the novel was set to play in the states sometime that summer. Somehow, despite Zulawski being one of (if not my all-time) favorite directors, I had completely missed the news that he’d made the film at all—his first in 15 years—or that it had debuted at the Locarno Film Festival over the previous summer (where it nabbed Zulawski the Best Director prize).

The randomness of this coincidence felt especially eerie given Cosmos’s focus on randomness and coincidence. After discovering the murdered bird, the novel’s protagonists begin seeing signs of some grand, overarching, and sinister design all around them. My sense of deja vu would increase tenfold by the time I finished the novel a couple weeks later, when news broke that the 75-year-old Zulawski had died of cancer. Cosmos was now the final novel and final feature from two of Poland’s most important and influential artists of the last century.

According to Zulawski scholar Daniel Bird (who also provided the film’s English subtitles), Cosmos was not meant to be any kind of grand retrospective on his career, since he didn’t know at the time that he was sick and had plans to make future films. And yet, watched first in the immediate wake of his passing, and now ten years later, I can’t help but see it as such.

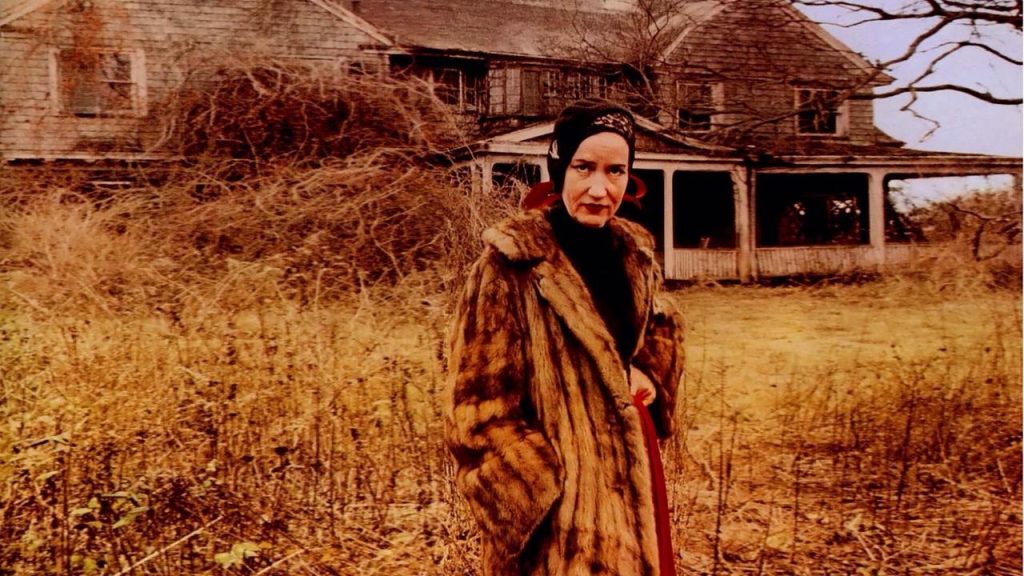

Zulawski’s modernized version of Gombrowicz’s story — which transports the action from a Polish pension in the Carpathian Mountains to a French-run bed and breakfast in the seaside town of Sintra, Portugal — is overflowing with his signature obsessions: romantic longing so intense it sends people into epileptic seizures and causes them to violently expectorate; love triangles that lead to madness, murder and suicide; stomach-churning closups of overripe or rotten food, insects and other slimy substances, human deformity; head-spinning surrealist dialog rife with all manner of monologue, diatribe, wordplay, obscenity, and nonsense; references to culture both high and low, from Charlie Chaplin to Luc Besson, Jean-Paul Satre to Star Wars, Henri Bergson to The Big Bang Theory (apparently Zulawski was quite fond of Sheldon); and the constant breaking of the fourth wall.

It’s that last touch that gives Cosmos such a strong sense of retrospection and finality. References to his own past work abound, from a cheeky dig at the title of his third feature, The Most Important Thing Is Love to a synopsis of Gombrowicz’s first novel, The Possessed, which just as well describes Zulawski’s most famous picture, the coincidentally (?) titled Possession (“Him and her, like an apple split in half”) to a climactic appearance of one his favorite visual motifs, the Eye of Providence.

Similar to Zulawski’s 1977 unfinished sci-fi opus On the Silver Globe and his 1984 erotic drama La Femme Publique, Cosmos ends by peeling back the cinematic curtain, as behind the scenes footage plays during the credits. At Locarno’s post-screening Q&A, Zulawski explained that his decision to step behind the camera after a decade and a half away sprung from his desire to “return to the origins of film.” Per Bird, via a special feature video included in the film’s Arrow Blu-Ray: “To be ‘true’ in cinema, Zulawski felt it was necessary to acknowledge its falseness’…”

In this, Gombrowicz’s novel made for the perfect vehicle, as it too constantly calls attention to its own artifice through its meta-narrative structure and flourishes (for example: the lead character is named Witold). Cosmos looks at how the search for meaning in an absurd universe often leads us to constructing our own meaning out of the chaos. If there’s a better metaphor for filmmaking, I haven’t heard it. The fictional Witold in Zulawski’s version spends much of the time turning his experiences into a novel, only to ultimately realize it’s not a novel he’s creating, but a film.

The headiness of this material, combined with the hysterical intensity of the film’s tempo and the disturbing content of its story (no actual animals were harmed, but bird and cat lovers will want to steel themselves before watching) make Cosmos a difficult watch — stateside critics were generally positive, although most reviews contain phrases like “impenetrable layer of gibberish”, “paradoxical aftertaste”, and “pure nonsense” — so it’s not surprising it remains underseen and underrated, even as Zulawski’s reputation amongst American cinephiles has grown exponentially over the past several years (thanks, for better or worse, to the rediscovery of Possession).

Ten years later, the mysteries of Cosmos continue to confound. Zulawski couldn’t have asked for a better swan song.

“Cosmos” is streaming on Kanopy and Kino Film Collection, and is available for digital rental or purchase.