As a 20-year-old film student, Bernardo Bertolucci was given the unique opportunity to serve as an assistant to poet and novelist Pier Paolo Pasolini on his directorial debut, 1961’s Accattone. In the years preceding it, Pasolini worked steadily as a screenwriter in the Italian film industry, but came to directing with no formal training behind the camera – or any preconceived notions about how to use it. In terms of blocking and shot composition, he referenced Renaissance paintings rather than other people’s films, leading Bertolucci to describe the experience as being akin to witnessing “the birth of cinema.” At the very least, it was the birth of Pasolini’s.

When he made Accattone, Pasolini was intimately familiar with depicting the lives of pimps and prostitutes onscreen. Co-writing the scripts for Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria, Mauro Bolognini’s The Big Night, Franco Rossi’s Death of a Friend, and Luciano Emmer’s Girl in the Window (not to mention a little film called La Dolce Vita) eminently qualified him to tell the story of a pimp cut off from his sole means of support when his stable of one is arrested on a charge of perjury and sent to jail. Even before that happens, the first news he gets about her is that she’s been hit by a motorcycle and is laid up in bed. Naturally, his instinct is to browbeat her into going back out that night, injured leg or no injured leg. He’s not about to pick up a trade so he can earn his own living, after all.

As portrayed by Franco Citti (younger brother of writer Sergio Citti, of one of Pasolini’s most trusted collaborators), Vittorio “Accattone” Cataldi is an indolent lay-about who hangs out with his similarly unemployed friends all day. (It’s telling that they berate Accattone’s younger brother for having a job when he passes them on the way to and from work.) Unsatisfied with his lot in life, he has the gall to blame his girlfriend Maddalena for dragging him down. “You think you bought me with the dirty money you give me every day?” he asks petulantly. “You ruined me.” It’s only after Maddalena is out of the picture that Pasolini reveals he’s married and has a child, but Accattone is persona non grata to his in-laws, who have zero interest in showing him charity. While visiting his wife’s place of work, though, he meets one of her coworkers and hatches a plan to turn her head and turn her out in Maddalena’s stead.

Upon its release, Accattone garnered so much attention for the novice director (some of which came in the form of virulent attacks from the right-wing press) that a follow-up was guaranteed. First, though, Pasolini gave consent for his assistant to take over a project he had written the story for, but put aside to make Accattone instead. Working with Sergio Citti, Bernardo Bertolucci fleshed out Pasolini’s story – with the proviso that the producer wanted “a Pasolini-type film” – and was given the job of directing it. Released in 1962, when Bertolucci was just 21, La Commare Secca (shown in the US as The Grim Reaper) follows an investigation into the murder of a prostitute as told through the testimony of witnesses who were on the scene. Its Rashomon-like structure reveals more about the witnesses than it does the victim, though, with their constant refrains of “I was just passing through” (i.e. “It has nothing to do with me”). Also, there are many discrepancies between what people say under police interrogation and what Bertolucci’s restless camera reveals about what they actually did. It’s difficult to single out the guilty when no one is innocent.

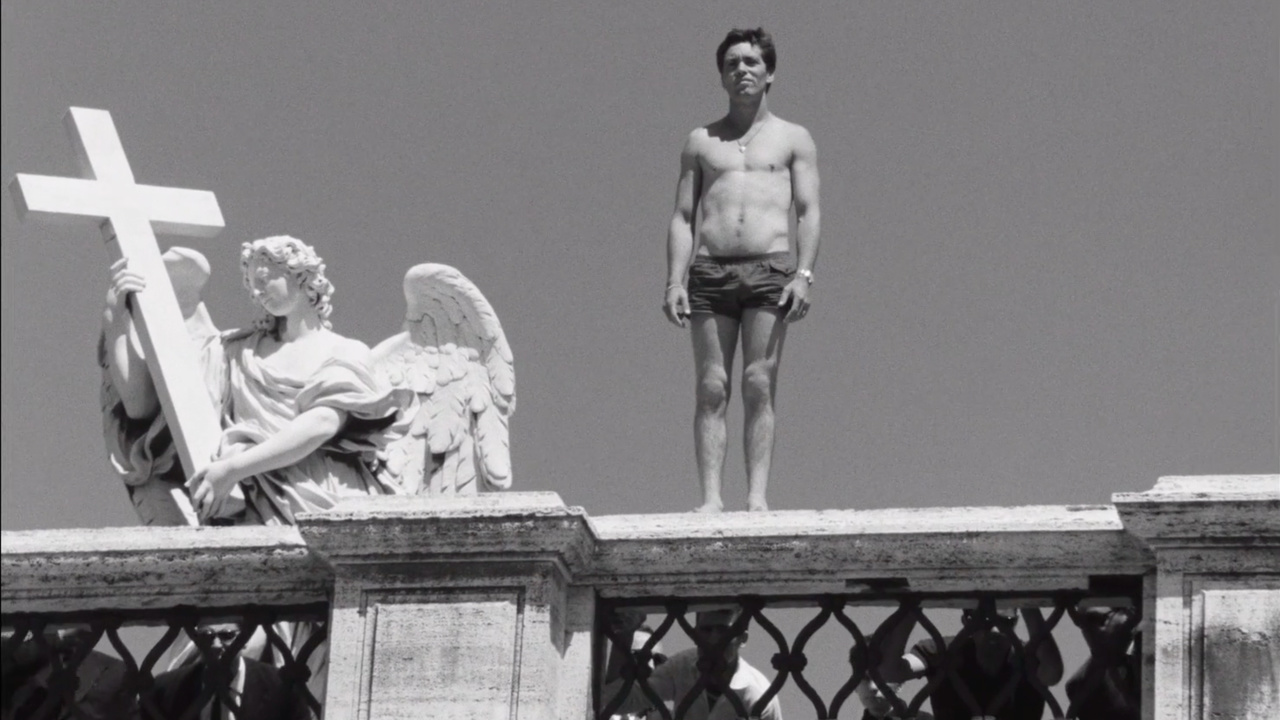

“She was a whore!” cries the perpetrator when he’s identified and arrested, adding, “What did I do? What did I do wrong?” This inability to see someone who sells her body as a person with agency and value carries over to Pasolini’s next film, 1962’s Mamma Roma, his first with an established star. Anna Mangani plays the larger-than-life title character, who’s ecstatic as the film opens because her pimp Carmine (Franco Citti again) is getting married. This means she can have her freedom and, most importantly, be reunited with her teenage son, who’s been raised by relatives out in the sticks. Bringing the boy to Rome only exposes him to bad influences, though, and he fails to appreciate the sacrifices she’s made – and continues to make – on his behalf.

One narrative strategy Pasolini adopts in both Accattone and Mamma Roma is skipping over potentially dramatic scenes and forcing viewers to play catch-up. In the former, the big one is Maddalena’s arrest, which precipitates Accattone’s eventual downfall. In Mamma Roma, the first comes just before her move to Rome, when Carmine seeks Mamma Roma out and demands money she has to go back onto the streets for a couple more weeks to get for him. In the space of a cut, she’s laughing as she loudly announces she’s leaving them for good, but this moment – a lengthy tracking shot as she walks and talks with whoever enters her orbit – is mirrored by one later on when she’s all tears after being forced to go back to work for him. “You should have known I’d be back sooner or later,” Carmine says, echoing Accattone by blaming Mamma Roma for his situation. “You ruined me,” he whines. “You turned me into a pimp.” He’s also enough of a bastard that after promising not to tell her son, he does anyway – another scene Pasolini elides.

Having thoroughly explored modern Rome’s seedy underbelly with his first two features, Pasolini next turned to the New Testament, taking a satiric swipe at pious Biblical epics with La Ricotta, his segment of the 1963 omnibus Ro.Go.Pa.G., starring Orson Welles as a director attempting to film a crucifixion scene. That was a warmup for the following year’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew, a decidedly down-to-earth depiction of the life of Christ. A curious choice of subject for an avowed atheist, but for the remainder of his career, Pasolini the director – and the man – would prove to be full of surprises.

“Accattone,” “La Commare Secca,” and “Mamma Roma” are streaming on the Criterion Channel. “Accattone” and “Mamma Roma” are also included in Criterion’s “Pasolini 101” boxed set.