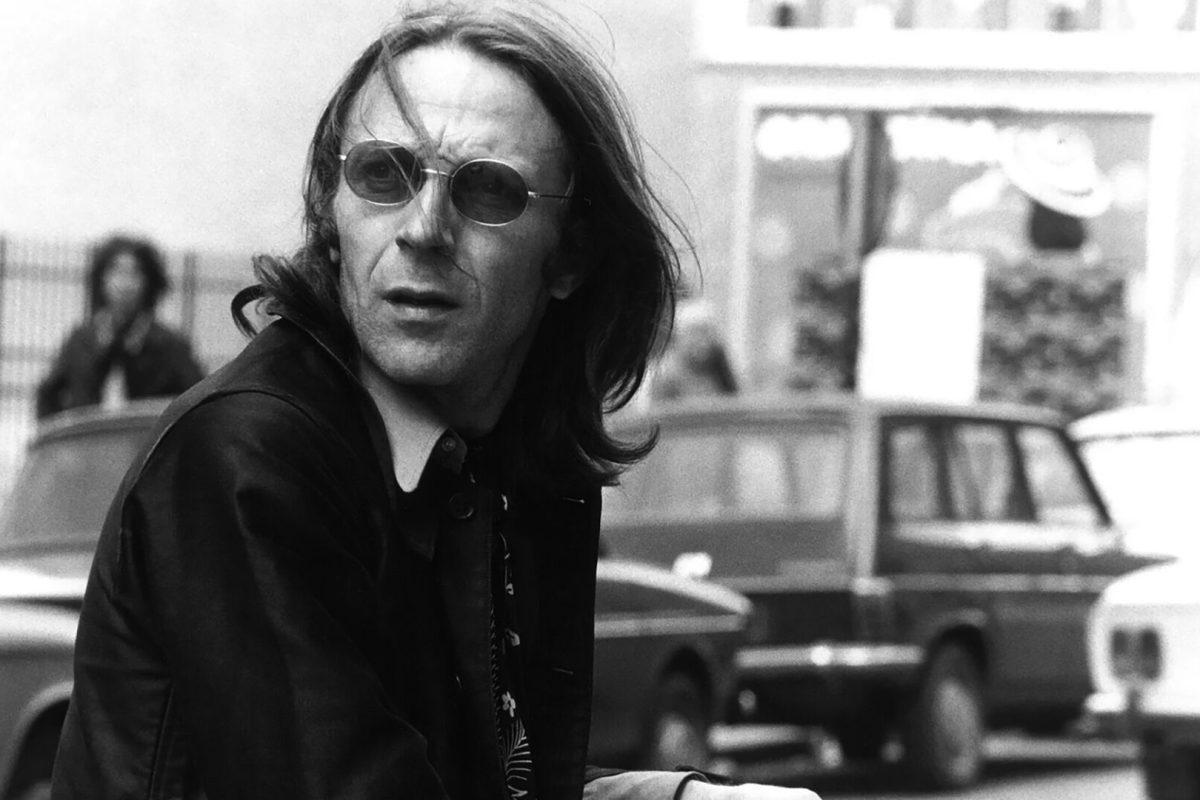

Among the more interesting additions to the Criterion Channel’s lineup this month is a strand focusing on the French filmmaker Jean Eustache – an enigmatic artist who truly let his work speak for itself and left the world far too early (partially immobilized in an accident, he took his own life in 1981, aged 42). He’s one of the key figures of French cinema, and yet, until very recently, he was a fairly elusive one as well.

An electrician by trade (he worked for the public French railway company when he first moved to Paris in 1957), Eustache became enamored with film through his frequent visits to the Cinémathèque Française, where he met François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard and the other New Wave directors. One of them, Paul Vecchiali, proved instrumental in getting his first short off the ground, which began a brief but intense career consisting of highly autobiographical works (he frequently depicted his hometown Pessac and its traditions).

Working primarily in the realm of short and medium-length films, Eustache completed only two fiction features. The first of these, 1973’s The Mother and the Whore, is his most famous contribution to cinema, not least thanks to its salacious title that makes the film sound much dirtier than it actually is: the moniker refers to the psychological archetypes matching the male lead’s two love interests (the plot is based on the director’s own private life), and the relationships are conveyed through words. Lots of them.

Upon accepting a lifetime achievement award in 2018, Jean-Pierre Léaud remembered how he spent three months memorizing his lines, as Eustache insisted the actors know the verbose script by heart and forbade improvisation on set. Adding to the difficulty, he decided to record the dialogue during filming – still not a regular practice back then – and only do one take for each scene. The result is a dense, captivating masterwork that enthralls for its entire 217-minute duration.

Somewhat surprisingly, given its talkative nature, black-and-white aesthetic, and theoretically punishing runtime, the film was a commercial success in France. The same couldn’t be said of Eustache’s follow-up feature, My Little Loves (1974): deliberately conceived as a polar opposite of its predecessor, it was shot in color, with very little dialogue, and was only two hours long. It wasn’t as well received, which may have contributed to Eustache not making another feature-length film (although he had a few projects in the works at the time of his death, including a sequel to The Mother and the Whore).

His untimely death led to the gradual disappearance of his body of work: as his son Boris held onto the rights quite firmly, the director’s films never received a home release, and rarely aired on television (when The Mother and the Whore was broadcast in France in 2013 to pay tribute to actress Bernadette Lafont, who had recently passed away, it was the first time it had been shown in thirteen years).

There were, essentially, two ways to view them: at archives and festivals, which relied on whatever vintage prints they had available (I was fortunate enough to attend the Turin Film Festival in Italy in 2018, which showcased the complete works of Eustache as one half of that year’s retrospective; the other half was Powell & Pressburger); or via the Internet, as the rights holders were unusually lenient about cinephiles accessing the films this way (these copies have since been removed, for reasons detailed below).

Then, in 2022, the big announcement came: Les Films du Losange (the French distributor of Lars von Trier, among others) had come to an agreement with Boris Eustache and secured the rights to his father’s entire oeuvre, the first step in a much-needed restoration process for all the films. The inaugural screening, of the newly restored The Mother and the Whore, took place in May of that year at the Cannes Film Festival, where the movie had originally premiered in 1973. It was a second chance of sorts, as the film proved divisive back in the day: Ingrid Bergman, who presided over the jury at the time, openly said she found it “regrettable” that France was represented by Eustache’s work, as well as Marco Ferreri’s grotesque satire La Grande Bouffe.

My Little Loves followed suit a few months later, with the restoration unveiled at the Lumière Festival in Lyon, one of the major events devoted to classic cinema and film preservation. Following these screenings, a traditional theatrical re-release was organized in France, where reissues get just as much media attention as new titles, and in other countries. And there was, of course, the long-awaited home release: coinciding with Eustache’s Criterion debut in the US, the same titles are now part of a French DVD and Blu-ray box set curated by Carlotta Films, one of the more prestigious archive labels in Europe.

As such, viewers can now enjoy twelve gems of Gallic filmmaking, ranging in length from 20 minutes to almost four hours: shorts, features, and a couple of projects commissioned by French television (including Eustache’s final film, Employment Offer, first broadcast a few months after his death). It’s an exhaustive trip inside the mind of a filmmaker who rarely spoke of himself publicly but drew from his own life for most of his work, wearing his heart on his sleeve and revealing himself with sometimes shocking candor via the filter of cinematic fiction.