Camp and high art commingle in Todd Haynes’ May December, and what results is sensational — in both senses of the word. The story within the story is loosely based on the ‘90s tabloid scandal of Mary Kay Letourneau and Vili Fualaau, but the script from Samy Burch adds another layer, introducing an actress who is playing the Letourneau analog in a film decades later, turning this movie into a commentary on the societal obsession with true crime as entertainment. Alternately darkly funny and profoundly sad, May December feels like a movie only Haynes could have made — and made so masterfully.

With Carol and Far from Heaven, the director nodded to the mid-century melodramas of Douglas Sirk, but May December somehow owes more to both the Lifetime variety of the genre and Ingmar Bergman works like Persona. With that dichotomy, May December possesses an eely quality; it slides between comedy and drama, from entertaining to unnerving. However, Haynes fully controls where it sits on that dial. It’s often sharply, oddly funny in its dialogue, but the filmmaker never lets you forget the underlying trauma of what occurred in the movie and in real life, both in terms of how fucked up the original act was and how fucked up it is that people were so engrossed by what happened.

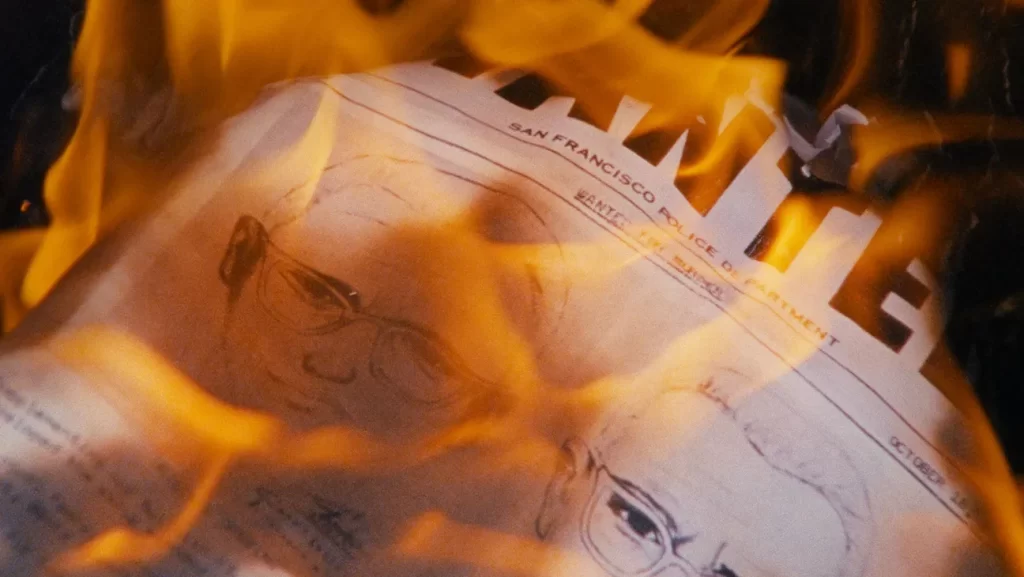

May December changes the particulars of the Letourneau story, but keeps the timing and the age gap roughly intact to nauseating results. Back in the ‘90s, 36-year-old Gracie (Julianne Moore) and 13-year-old Joe (Charles Melton) met while working at a pet store and began a relationship that led to her pregnancy and their eventual marriage. In 2015, they’re the parents of three children together (plus she has grown kids from her first marriage), and their story is set to become an independent movie starring famous actress Elizabeth (Natalie Portman). The star joins them at their home in Savannah, intent on learning more about their relationship and capturing Gracie’s idiosyncrasies for her performance.

It’s significant that this movie wasn’t titled “May December Romance,” the full term often applied to an older man and a much younger woman that obscures the power dynamics even when both people were consenting adults, which wasn’t the case here. In May December, the inciting incident back in the ‘90s wasn’t seduction; it was rape. It’s also meaningful — and entirely intentional — that the film takes place in 2015, decades later, and refrains from depicting what happened. May December refuses the audience the experience of witnessing the original crime, focusing solely on its aftermath and the various perspectives on what happened.

With this approach, Haynes examines our societal obsession with salacious narratives like these, as people draw entertainment from the retelling of real events. These aren’t simply fictions without victims and repercussions; they affect real people who have been impacted by what happened, and continue to live with it years later. Yet it isn’t just the audience who is feeding off these people’s tragedies; with Portman’s actress character, Haynes hilariously pokes at actors and what they gain from taking on these sorts of roles. He also digs into the differing views on the relationship, its origins, and who these people really are as a result.

With Gracie, Elizabeth, and Joe, May December centers on three distinct pairings and their varying dynamics, as well as the triangulation between the three people. Cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt shoots them in medium two shots, with minimal cuts from editor Affonso Gonçalves that let these actors’ astonishing work shine. The characters and accompanying performances evolve, challenging both our initial conceptions of them and the cultural weight of their real-life counterparts.

Unsurprisingly, Moore and Portman give nuanced turns, bouncing and reflecting off one another in fascinating ways, especially as Elizabeth spends more and more time with her inspiration, picking up her way of speaking. Portman’s role is especially layered, with the performance within a performance, though her character isn’t the only one acting. The real surprise here is Melton, who doesn’t just hold his own with these two Oscar winners. As the film progresses, he reveals more and more of Joe, showing a vulnerable man who still has echoes of the child he was when he was raped.

The attention to detail goes beyond just the acting, with the production design providing additional depth to the story. Gracie and Joe are living in a house whose furniture, wallpaper, and other decor is stuck in the past. The couple may have aged, raising three children together, but they’re still stuck at the time when she was 36 and he was 13. Their children are growing up — one is in college, and the twins are graduating from high school — but Gracie and Joe are in a state of arrested development. She often treats her husband like a child, which is fitting given that he is the same age as her son from her first marriage. The mise-en-scène contributes to the larger sense of things being “off” in this home.

What results is a spiky film, simultaneously challenging and pleasurable. The joys of May December lie in both its black humor and at what Haynes and his team have accomplished, but it doesn’t shy away from the complexities and ugliness either. This feels like a Haynes film on every level, playing with themes and styles the director has used before, while still creating something entirely fresh within his oeuvre.

A-

“May December” is in theaters now and on Netflix Friday.