Through all my years of covering the Sundance Film Festival on the ground, I harbored a secret desire: to show up at the end. If one arrived for the last, say, four or five days, they’d have the advantage of pre-screening: you would have already heard about the initially hidden gems, you’d have learned which of the high-profile premieres were actually worth your time, and you’d know which movies only got in because of a slumming movie star. Trouble is, the economics of film festival coverage prohibit this laissez–faire approach; when people are paying you to cover a film festival, they are typically paying you to go to the very first screenings, over that first weekend, and file accordingly.

My choice to cover Sundance virtually this year, as detailed in my last report, was primarily a financial one. But I realized, once I started figuring out my viewing schedule, that I was finally doing the Sundance of my dreams; I have already heard, from other critics, which films to seek out and which ones to carefully avoid, hence these dispatches consist primarily of “A” and “B” reviews. On one hand, maybe I should’ve watched one of the dogs, in the name of “balance” (or, even worse, critical street cred). On the other, why waste two hours not watching something great?

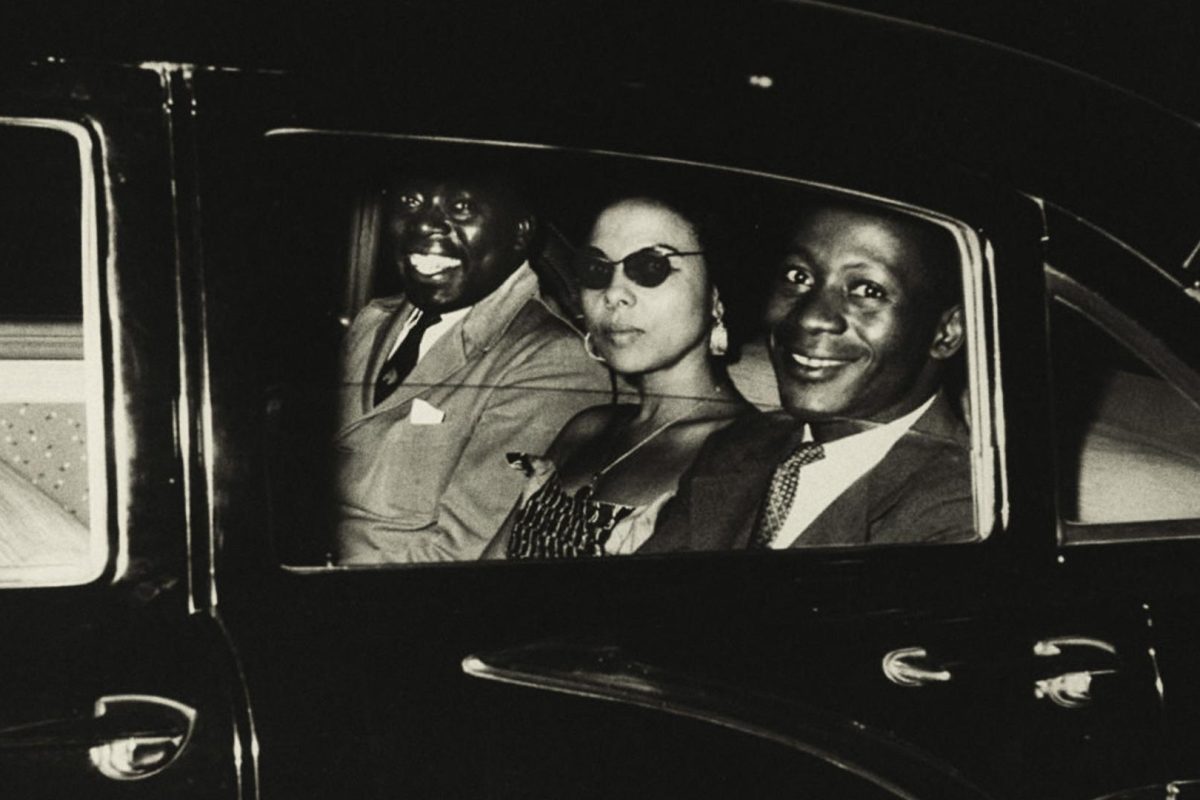

Sundance’s documentary slate is reliably high-quality, and the samplings I took from this year’s selections were no exception. Belgian filmmaker and multimedia artist Johan Grimonprez’s Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat sounds, from its logline, like a fairly straight-forward historical documentary, chronicling the struggle for Congolese independence from the late 1950s through the mid-1960s. But Grimonprez eschews most of the stylistic markers such a description calls to mind; there are no talking head interviews and no contemporary voice-of-God narration, and he shines the story through the prism of the era’s jazz music, as well as that music’s intersections with the politics and protest of the moment.

So the jazz gives the picture its heartbeat, its rhythm; it’s a masterfully edited case of form following function, medium marrying message. Soundtrack is a long movie — just shy of 2.5 hours — but it moves like lightning, its flurry of information and insight powered by sly, harp juxtapositions and unexpected connections. Some of this footage (much of it, in fact) is downright shocking, but Grimonprez lingers on nothing; he’s building a case, mounting an argument, and the end results are devastating. Grade: B+

“Devastating” is about the only appropriate description for Black Box Diaries, in which Japanese journalist Shiori Ito details her journey as a survivor of sexual assault. Hers occurred in April 2015, at the hands of a powerful and respected colleague; she went public two years later, in the face of infuriating hostility from members of the media and police investigators. (“The law has its limits,” one informs her. Yeah, no shit!)

Ito isn’t just the subject of Black Box Diaries — she’s also its director, and that cinematic intimacy, that raw, open-wound quality, gives the picture much of its considerable power. She’s also, luckily, a compelling protagonist, tough and resourceful and determined, taking on not just one well-connected journalist, but an entire corrupt system. It’s a tough sit, but an important one, and there’s a telephone conversation near its ending that’s the single most moving thing I’ve seen at this festival. Grade: A

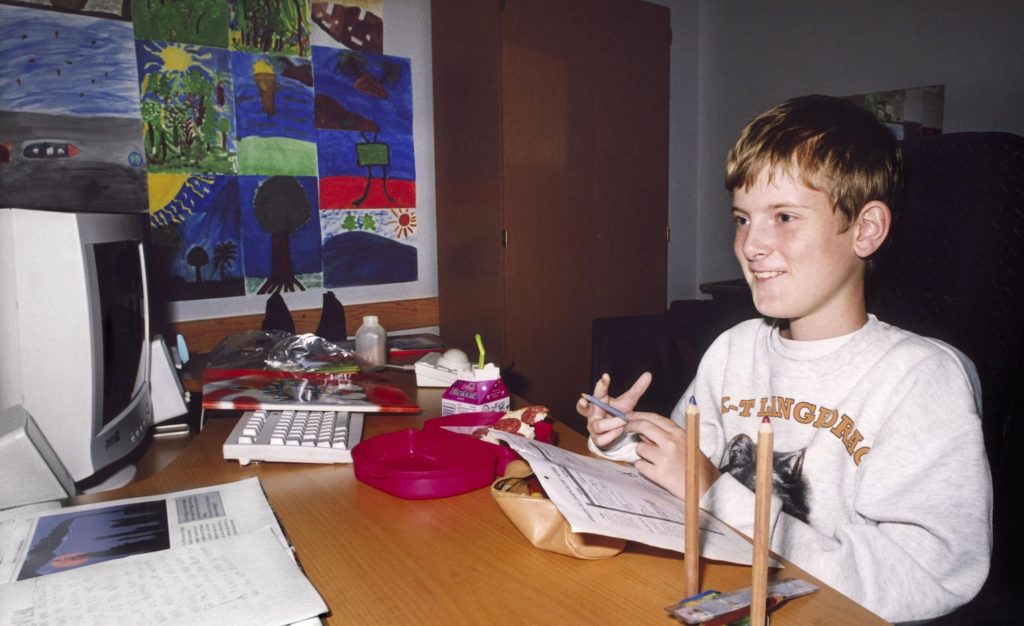

There’s a not-inconsiderable chance you’ll shed a tear or two at Ibelin as well. Director Benjamin Ree made one of the most memorable movies of Sundance 2020, The Painter and the Thief; here, he focuses on a handful of even more unusual relationships. His focus is on Mats Steen, diagnosed as a child with a rare and incurable degenerative muscular disease. This material is almost unbearably sad, with plentiful home videos showing his sharp decline; he died at age 25.

He spent most of the back half of his life online, playing video games, an understandable choice. But it was only after his death that his parents discovered “a wold we knew absolutely nothing about” — how their son had become part of an RPG community, creating an alternate personality of “Ibeline Redmore, famed detective and nobleman,” and creating friendships and connections therein. Ree cleverly creates the fantasy that became Mats’s real life, using chat logs, animation, and voice actors, and showing how this digital life allowed him experiences he couldn’t have otherwise. It’s a warm personal profile, but also one of previous few movies to really get what it is to live online. Grade: B

The stats behind J.M. Harper’s As We Speak are sort of astonishing: since 1990, more than 700 criminal trials have used rap lyrics as evidence and exhibits — the idea, as one expert puts it, that “this artistic expression is actually a confession.” Young Thug is the highest-profile example, but there are many, many more; Harper’s film uses SoundCloud rapper Kemba as a kind of tour guide, as he travels around the country, seeking out and commiserating with fellow artists, delving into the history of Black music as commentary and the stigmatization of hip-hop, while other musicians and legal experts provide context.

As We Speak wanders a bit afield, and sags somewhat in the middle (the Shakespeare sidebar is a bit of a cliche by now). And some of the documentary footage, especially the conversations and the set-ups for them, feel awfully staged. But I frankly don’t mind forfeiting a bit of verite realism for visual stimulation, and many of Harper’s other innovations work (particularly the inventive animations). Snappily assembled and thoroughly thought-provoking, this one should find a welcoming audience when it hits Paramount+ in February. Grade: B-

Great documentary filmmaking is often about great editing, and there’s one edit early in Union that’s a doozy — a razor sharp cut from the grind of an Amazon factory to Jeff Bezos going into space. Rarely have two married images said more about income inequality and working class rage, and they motor this honest-to-goodness underdog story, which details how the workers at an Amazon packaging facility on Staten Island banded together to form the first union in the company’s history.

Directors Brett Story and Stephen Maing adopt a fly-on-the-wall approach, telling this story from ground-level. These things don’t just happen — they require weeks, months, even years of hard work and sacrifice on the part of organizers, and the filmmakers capture not only the intensity of their work, but their internal tension over the approaches and strategies of the strong personalities involve. (They also capture the NYPD doing a little state-funded union busting, which might comes as a shock to anyone who hasn’t had much interaction with the NYPD). It’s genuinely inspiring stuff, even as the filmmakers wisely choose not to conclude their story at the “happy ending.” Grade: A-

The celebrity bio-doc is a Sundance mainstay, and the most notable of this year’s options is Luther: Never Too Much, a look at the life and career of the great R&B singer, songwriter, and producer Luther Vandross from director Dawn Porter (Trapped, John Lewis: Good Trouble). Its best stretch is its opening, a good old-fashioned up-and-comer story, in which Vandross hustles his way up from background singing, vocal arranging, and commercial jingles into the spotlight, with stops in Bowie’s studio and at Sesame Street along the way (the archival footage is priceless).

Nothing is easy, of course, and Porter sensitively touches on his struggles with his weight, depression, career ups-and-downs, and sexuality, though I’m not entirely sure the decision to hold off on hitting the last point until the back third works (it’s something of an elephant in the room until then). But she wisely respects, or at least contextualizes, his privacy. Luther is a bit fluffy, as these things typically are (particularly when they’re official and authorized and all that). But it’s ceaselessly entertaining. Grade: B-

The “Date with Dad” program isn’t nearly as creepy as its name — the group organizes father-daughter dances for incarcerated men and their daughters, many of whom are unable to see them in person on a regular basis thanks to prisons converting to (paid, of course) video visits. That’s one of the little pieces of infuriating information contained in Daughters, Natalie Rae and Angela Patton’s winner of the Festival Favorite award and the audience award for U.S. documentary, though their primary focus is on the 2019 dance.

Any father participating must complete a ten-week group counseling course, where they talk openly and vulnerably about the mistakes they’ve made and their paths going forward. Those sessions are intercut with candid, often raw interviews with their daughters, detailing the genuine struggles of their lives (and those of their mothers). Some may argue with the selective information we’re given — what most of these men are in jail for, for example — but those facts are ultimately beside the point, because no child should be punished for their parents’ mistakes. The reunions, on the big day, are as stirring as their eventual separations are heartbreaking; this is a powerful piece of work, expertly using the intensity of its emotions to make a strong intellectual statement. Grade: A