The online component of the Sundance Film Festival began in 2021, when, like so many of their fellow festivals, COVID restrictions made an in-person celebration in Park City impossible. But unlike those other fests, which retreated to an in-person-only presentation as soon as they could, Sundance has kept its online component in place — not everything on the slate, but enough to allow indie film lovers all around the country to get an early peek at some of the year’s most promising movies. And for those of us who cover the festival on the ground, it gives us a chance to play catch-up when we get home, checking out titles with building buzz, or smaller movies that may have been lost in the shuffle.

The big winner of the fest, at least in terms of awards, is Josephine, writer/director Beth de Araújo’s patient, methodical, delicate story of a young girl who is asked to shoulder burdens that most adults would shudder at. Her name is, indeed, Josephine (played by an extraordinary young actress named Mason Reeves), and early one morning, she and her dad (Channing Tatum, beautifully understated) are playing in Golden Gate Park. They get separated, and while looking for him, she witnesses a brutal, horrifying sexual assault.

It fucks her up, understandably — particularly when the police reveal that she was the only witness, so it’s up to her to Do What’s Right and testify. The question of how she can do that, and what it will do to her already-damaged psyche, consumes the picture, and Araújo powerfully uses subjective camera and visceral, internalized filmmaking to put us in Josephine’s head. It’s genuinely upsetting but never exploitative, and the complex nuances of the parental dynamic (Gemma Chan is also excellent as Josephine’s mom) are particularly finely tuned. This is a movie you’re going to be hearing about all year.

The most of-the-moment movie at this year’s fest was Felipe Bustos Sierra’s Everybody To Kenmure Street, a minute-by-minute tick-tock of a stunning, impromptu protest in 2021 in one of Glasgow’s most diverse neighborhoods, in which the U.K. Home Office attempted a dawn raid, on Eid, arresting two local men for deportation. Word got around, and soon the street was teeming with locals who were willing to take whatever steps were necessary to protect their neighbors.

The fact that this film was unspooling just as similarly brave neighbors in Minnesota were taking the exact same stand for their neighbors could just be coincidence — or it could be a vivid illustration of how we’re all in the fight against fascism together. Whatever the case, Sierra’s documentary is a stunner, detailing the tactical and emotional progress of the day as it goes, impeccably assembling on-the-ground footage, after-the-fact interviews, and inspired use of stand-ins for participants who wish to remain anonymous. This is an empowering, inspiring movie, a blueprint for how to do what we’re apparently going to spend the next few years doing in our communities.

The biggest disappointment of the festival was undoubtedly Zi, writer/director Kogonada’s clear attempt to go back to his roots after the failure of A Big Bold Beautiful Journey by making a low-budget, character-driven indie that even goes so far as to reunite him with Columbus leading lady Haley Lu Richardson. It looks the part, shot on film in Academy ratio, but instead of back to basics, it’s giving middling student film. The dialogue is stilted, the plot is torpid, and the acting is surprisingly (particularly from Richardson) wooden. Zi looks great, and has some clever edits, but that’s about all you can say in its favor.

One of the thrills of this festival is discovering an exciting new voice, and that’s certainly an accurate description of writer/director Rachel Lambert. Her film Carousel is a tricky thing, sliding us into a story decades in progress, and letting us figure out the backstory from context and subtext instead of clunky exposition. Chris Pine plays Noah, a divorced, small-town doctor and dad; Jenny Slate is Rebecca, his high school girlfriend who has moved back to town and, wouldn’t you know it, is Noah’s teenage daughter’s debate coach.

There’s little doubt they’ll rekindle their old flames, and that complications will ensue; Lambert isn’t trying to shock us with a twisty narrative. Instead, she stuns us with the clarity of her perspective, approaching these conflicted, stubborn, difficult, lovely people with warmth and empathy. And she doesn’t take the tack of too many indie filmmakers, assuming that the camera is only there to photograph the dialogue; Carousel is full of unexpected compositional choices, invitations to look where we might not think to. But sometimes she just lets a scene play out, lets the actors act, allowing them to build a moment and find an elusive truth. Slate is great, as she always is, but Pine is tremendous — this is the best work he’s done to date, by a country mile. There’s a moment, in the middle of a painful argument, where he wipes off the counter with his hand, and it’s the smallest little gesture, but it feels like a revelation. The movie works in much the same way.

Writer/director Adam Meeks made Union County with the cooperation of the Adult Recovery Court in his hometown of Bellefontaine, Ohio, using non-actors (and real addicts) to tell his story, and probably the highest compliment one could pay stars Will Poulter, Noah Centineo, Elise Kibler, and Emily Meade is that they don’t stick out as “actors”; they manage to capture the same kind of truthfulness and honesty as the real folks. The film around them is noteworthy as a recovery narrative that really is about the work, the trouble, the imperfections of shaking addiction; Meeks doesn’t soften the edges, the way too many Hollywood dramas do, so it feels like a story told from the inside.

He dodges other traps as well; there’s a girl who might be a love interest in another movie but not this one, and there is a perpetually wronged family member (Meade, so terrific on The Deuce and tip-top here in a completely different kind of role) who is not going to give us the kind of warm and fuzzy forgiveness arc that we’re waiting for. Its refusal to go for easy sentimentality will certainly make this one a hard sell, but those who’ve brushed up against this world will recognize the uncompromising honesty of what Meeks is reaching for, and often achieves.

Night Nurse opens with a strange, sexy scam call, a young woman breathlessly calling “Grandpa” to ask for cash to get out of a scrape. The vibes are strange and horny right away, and they stay that way for the 95 minutes that follow. The premise is utterly implausible — the night nurses for a charismatic resident of a luxury retirement community turn into his little harem of playmates and accomplices — so it’s worth commending writer/director Georgia Bernstein for harnessing enough sinister energy and unapologetic kink for it to work, at least in spurts. It falls apart a bit in the home stretch, but the exquisite closing lines (and last looks) almost patch it up.

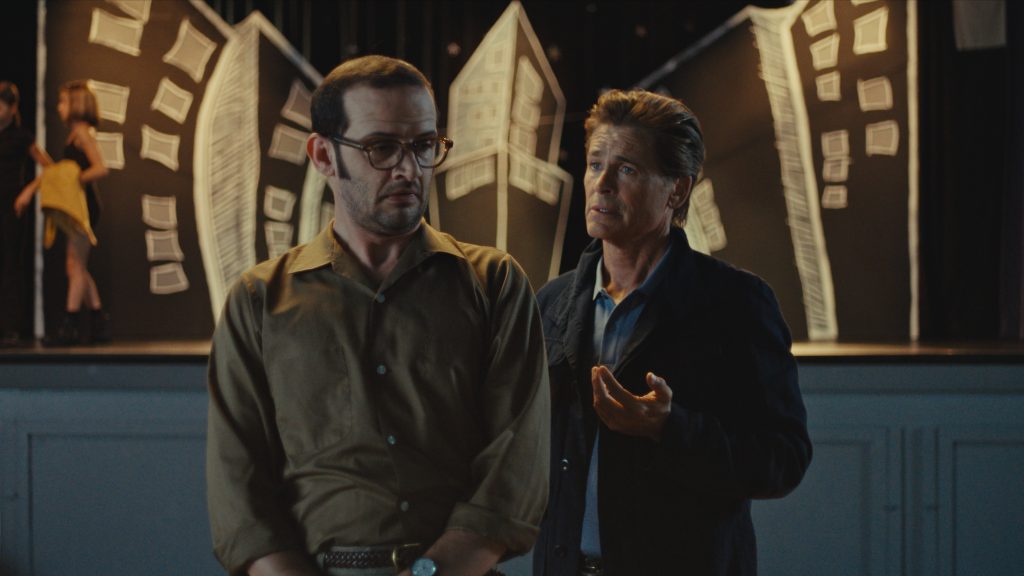

The Musical is a tricky one to write about, since its best joke — and one that it spends much of its running time working around — is really one that’s best kept secret. The set-up is juicy enough: Will Brill is Doug, a failed playwright and miserable middle school teacher whom we meet in the midst of a bad breakup with the school’s art teacher (the always luminous Gillian Jacobs). His tailspin gets worse when he discovers she’s started dating the school principal (Rob Lowe, harnessing his best Bill Lumbergh energy), prompting embarrassing interactions and increasingly frequent airings of petty grievances.

“Everybody talks about the power of love,” he says, in a conspiratorial voice-over. “But nobody ever talks about the power of spite.” And with that, he punts the school’s planned production of West Side Story for an original musical of his own composition. And there we get into the territory of insanity, and I’ll reveal no more; suffice it to say that at its best, The Musical harnesses a kind of nutso gonzo energy that recalls Jody Hill’s work, and if it starts off a little bumpy, its closing scenes are some of the most inspired screen comedy I’ve seen recently.

Brydie O’Connor’s Barbara Forever opens with the filmmaker Barbara Hammer testing her camera and testing her microphone. Once they’re good to go, she gets in front of the camera and removes her robe, and stands before us in the altogether. It’s an appropriate image with which to begin this documentary, as Hammer was a filmmaker who fearlessly gave herself to her art. “My life has been lived on film,” she says. “I’m creating a lesbian history in a world where we’re invisible.”

O’Connor spends a fair amount of her running time detailing that history, so we better understand how Hammer fits into it. The framework, at least initially, is that Hammer is donating her vast archive to Yale, so she’s cataloging her work and grappling with her legacy, laying out her philosophies of both filmmaking and living. But eventually, the work became inseparable from her private life, and the intertwining of them became both her blessing and her burden. And when she is diagnosed with cancer, Barbara Forever becomes a story of mortality, and how she knew that her work would give her an immortality that her body couldn’t manage. This is a fulfilling portrait of an inspiring artist.

Soul Patrol feels like something of a documentary counterpart to Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods, telling the story of Company F, 51st Infantry, a long-range recon patrol that operated behind enemy lines during the Vietnam War and was comprised of six Black men — the first Black special operations team of that conflict. Soldiers of color were disproportionately represented in country (and disproportionately wounded and killed), and director J.M. Harper strikes a fine balance between the micro and the macro, detailing the specificity of their background and experience there with the contradictions of fighting for a country that did not care much about them back home.

But Harper leans too heavily on reenactments and dramatizations, attempting to ramp up the cinematic elements of a story that’s already plenty compelling. Goodness knows it’s laudable for a filmmaker to try and expand on the straightforward approach of interviews and archival footage (much of it shot by the subjects themselves), but images of surviving members encountering their younger selves simply make us think of Da 5 Bloods, and Soul Patrol doesn’t come out ahead in those comparisons. It’s worth seeing, a story worth telling, but you’ll wish it had gotten out of its own way.

The 2023 raids on the Marion County Register, a tiny local Midwestern paper, became a worldwide media story — a microcosmic example of how the Republican “enemy of the people” rhetoric is applying itself to everyday life. Sharon Liese’s Seized examines the story one year later, as the dust has settled but the wounds in Marion, Kansas have certainly not closed.

Liese uses the arrival of a cub reporter for a one-year stint at the paper as a useful entry point, basically looking over his shoulder as he learns the ropes of this small town (population 1890) and the still-simmering resentments that led to that First Amendment firestorm. She also takes the trouble to complicate the story a bit, airing the complaints of the town against the paper and its editor Eric Meyer — some of them valid, none of them excusing what happened on that bizarre day in 2023. A few key voices are missing and missed, but overall, Seized is an even-handed and enlightening piece of work.

He was born Joe Engressia, and born blind, which led to an early fascination with the telephone — how it worked, and how to make it work. That fascination, combined with his perfect pitch and ability to whistle any tone he wanted, made him one of the first “Phone Phreaks,” telephone hackers who figured out how to make free long-distance calls (back when they cost a not-insignificant amount of money) and became folk heroes. I assumed this would be the primary focus of Rachael J. Morrison’s documentary Joybubbles; delightfully, that’s just its starting point.

It takes its title from the name the former Engressia legally adopted in 1991, reflecting his childlike personality; this is a refreshingly gee-whiz criminal mastermind, who subsequently made friends and spread goodwill via phone messages and other acts of shared goodness. His good vibes are infectious, and Morrison lucked into scores of archival audio that convey a personality of genuine charm and goodwill. The filmmaking matches that spirit — her use of archival film clips and original animation feel handmade, assembled from unjustly discarded spare parts — making Joybubbles one of the warmest documentaries in recent memory.

And with that, Sundance 2026 comes to a close, as well as its time in Park City. But next January, the festival will unspool in its new home of Boulder, Colorado, and we’ll see if its particular alchemy can be replicated elsewhere. Until then…