Much has been made in the discourse over the past several years about the concept of the “unlikable woman.” It seems every week another piece of pop culture made by, or even just featuring, one must be rated on a scale of acceptability. But public, and usually paternal, fretting over the supposedly indecent behavior of anyone who identifies as female is hardly new. One need look no further than the initial reception of John Schlesinger’s 1965 satire Darling, which had its U.S. premiere sixty years ago this week. “A fickle wench,” wrote New York Times critic Bosley Crowther of anti-heroine Diana Scott (Julie Christie in her Oscar-winning role). “Empty of meaning,” declared Pauline Kael in Vogue. But time has been kind to Schlesinger’s corrosive vision of Swinging London, which now feels like a harbinger of our relentlessly self-image obsessed present.

Schlesinger isn’t subtle about the point he’s trying to make. Right from the opening credits – featuring a poster hanger pasting a splashy ad of Diana’s face over a P.S.A. about famine relief – he wants us to pay as much attention to what’s going on beneath the glossy surfaces as the beauty of the images themselves. Ostensibly, Diana’s voice-over unspools as an interview she’s giving to a reporter for Ideal Woman magazine. But it doesn’t take an eagle-eyed viewer to notice how often the manner in which she describes her thoughts and feelings is at odds with what’s happening onscreen. Everything is a commodity to be polished and sold in this world, including your own life.

The film is split into essentially three acts, all of which are concerned with distinct arcs in Diana’s career. We first meet her as a fresh-faced twenty-year-old new arrival in the city who’s plucked out of a crowd for a woman on the street interview. She’s immediately taken with her interlocutor Robert Gold (Dirk Bogarde), who exudes an intelligence and sophistication that feels seductively modern to her, as the pair banter about the true meaning of conventionality. Nevermind that both of them are married to other people; an affair becomes inevitable, setting up a pattern for Diana that will repeat itself throughout the remainder of the runtime. Soon enough they’ve both left their spouses and moved in together, at which point Diana begins looking for something, and someone, else to occupy her time.

In the script’s conception of Diana, she’s a woman whose most salient quality is how easily bored she gets. She must always move forward, shark-like, or risk curdling into cruelty towards those she loves. Not content with the stable but stultifying life that Robert provides, she finds herself entangled with dilettante advertising executive Miles Brand (Laurence Harvey), who has access to the high society she craves. He’s also bisexual, and introduces her to the queer circles of Paris. Though he wasn’t out at the time he made Darling, Schlesinger himself was gay, and would explore these subjects in further depth in later work like Midnight Cowboy and Sunday, Bloody Sunday. Here, though, it feels like one more milieu that Diana tries on, then carelessly discards.

It’s in this middle section that Schlesinger’s critique of the era’s mod culture crystallizes. While television wasn’t exactly new at the time, its utility as a manipulative tool was rapidly increasing. In scene after scene on film sets and in advertising board rooms, Schlesinger and screenwriter Frederic Raphael hone in on the medium’s uniquely insidious appeal: that the people who manufacture its unattainable images are just as susceptible to its false promises as the general public. “Do you buy her?” Miles asks a fellow executive of a picture of Diana. But his answer would flatter rather than horrify her, particularly as the glimpses she catches of her own face in the mirror grow increasingly unbearable.

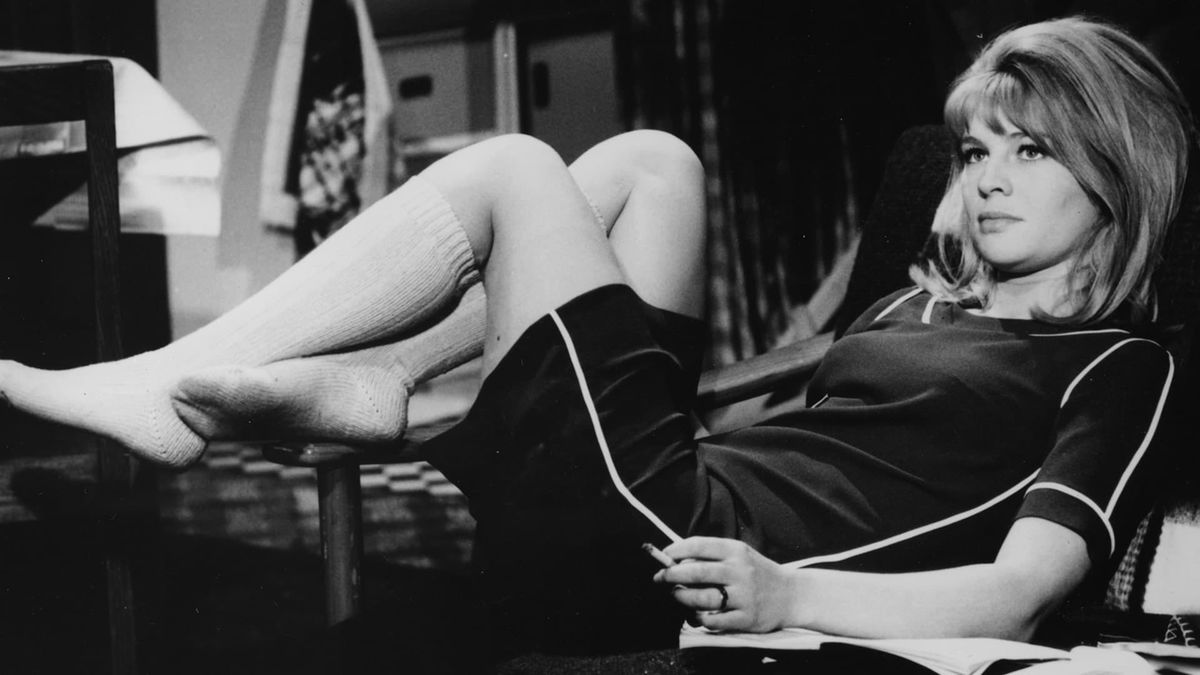

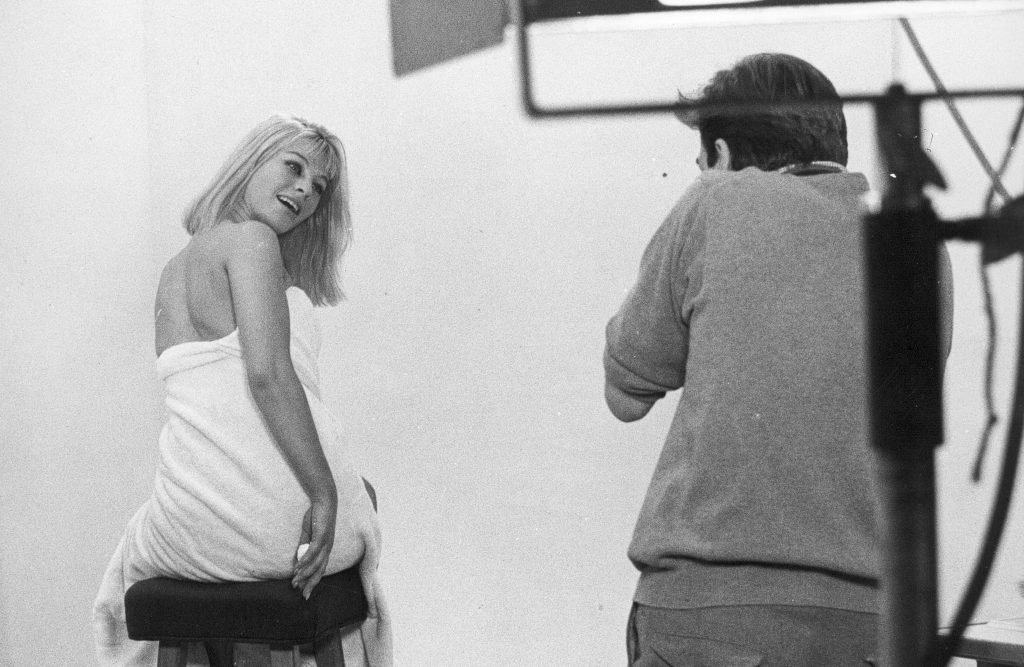

It’s a tightrope role and Christie, who always seemed to be appreciated more for her beauty than her considerable acting ability, walks it brilliantly. Diana is a vain and shallow person, and some critics at the time unfairly dinged her performance by attributing those same qualities to Christie herself. What those complaints miss is how tricky making a character like that interesting to audiences can be. It’s the sort of thing that makes or breaks a picture, but Christie’s irrepressible charm shines through even in Diana’s most loathsome moments.

By the final act, she’s grown weary of the transactional nature of her life in London and fled to Capri. She meets a widowed Italian prince and while she’s initially resistant to his marriage proposal, she eventually accepts and finds herself crowned Princess Diana (an eerily prescient coincidence, given that it was still roughly fifteen years before Lady Spencer – a woman whose own predatory relationship with the press would end in tragedy – ascended to the British throne.) Newsreel footage shows a smiling Diana caring for her seven adopted children and participating in charity work. Privately, she remains as miserable as ever, and surely will long after the film ends. She might have the coveted spot on the front of the magazine, but we know there’s nothing but blank pages underneath.