Fictional monsters have often been used to examine the “other” within ourselves. But the various incarnations of The Mummy — in 1932, 1999, and now 2017 — have touched on America’s interactions with foreign, exotic “others.” In a nutshell, each version follows the same narrative: stupid English-speaking people unearth an ancient mummy that brings bad tidings and must be destroyed. Our “new world of gods and monsters” often leaves us wondering if the real monster is us.

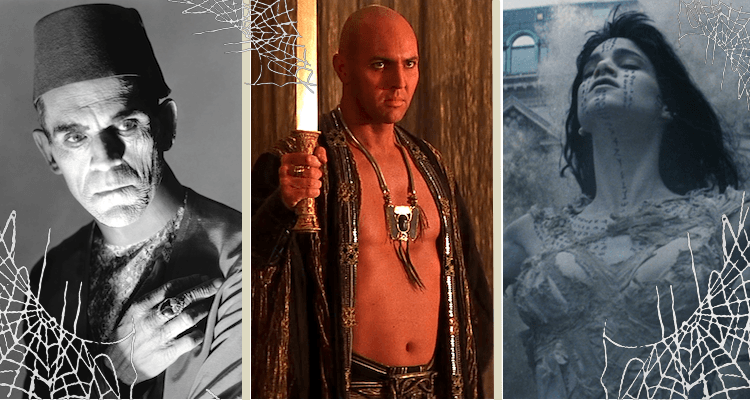

Producer Carl Laemmle’s 1932 film is the granddaddy of them all. Directed by Karl Freund, the film follows a group of blah Westerners after they uncover the corpse of Imhotep (Boris Karloff), an Egyptian priest punished for falling in love with a vestal virgin of Isis. Under the name Ardeth Bey, Imhotep returns to wreak havoc in the 20th century. It’s from this film that the 1999 remake takes a majority of its plot, and which the 2017 edition all but kills off.

The Mummy’s tale of reincarnated love and exotic attraction owes its life to the film that preceded it, Universal’s 1931 version of Dracula. In fact, The Mummy is almost a beat-for-beat remake of the Lugosi feature, complete with opening credits accompanied by Swan Lake. The vampire’s black cloak and bloodsucking is replaced with a similar blank slate of a monster whose immortality, exotic paganism, and desire for a woman is perceived as evil and must be destroyed — this in spite of advanced characterization that seeks to humanize Ardeth Bey as a man whose actions are compelled by love. Unlike the remakes, the worst thing Bey does in the film’s scant 73 minutes is lust after the half-Egyptian Helen (Zita Johann), the reincarnation of his beloved. Also mirroring the Dracula story, Helen is susceptible to foreign influences due to her Egyptian parentage, is seduced by Bey, and must be saved by a white male (with the added implication of his being a Christian) who truly loves not just her but her soul.

Released 10 years after the discovery of King Tut’s tomb by Howard Carter, 1932’s The Mummy simultaneously revels in the untold treasures waiting to be explored and the presumed mysterious and mystical world the English and Americans knew little about. Archeologists Sir Joseph Whemple and Dr. Muller, characters who open the film’s first half, emphasize they are not grave robbers — claims that followed Carter and his benefactor Lord Carnarvon upon finding Tut — but are interested purely in an exploratory capacity.

By the time of the film’s release, America was in the third year of the Great Depression. England was in the midst of theirs as well, known as The Great Slump. The advent of cars and planes — Amelia Earhart and Charles Lindbergh were popular during this time — told people they weren’t necessarily limited by geography, but to experience it cost money and could be dangerous. As Dorothy Gale would say seven years later, “There’s no place like home” — you might meet an angry mummy!

The Mummy also illustrates the U.S.’s rise of isolationism in the wake of World War I and the lead-up to World War II. Ardeth Bey represents all that is exotic and mysterious but also frightening. This explains why Muller and Whemple discuss their “exploratory” nature in finding the tomb: they’re declaring that, unlike some Americans who want to intervene in foreign affairs for profit, their motives are pure.

Sixty-seven years passed before Universal attempted another mummy, this after cannibalizing the original for sequels and comedic spin-offs. Stephen Sommers’ 1999 incarnation tells the same general story, with the addition of new characters who bring it in line with ‘90s sensibilities toward the Middle East and women. All three iterations of the story shy away from taking place within Egypt itself; the ‘32 and ‘99 editions don’t even explicitly state where they’re set. The ‘99 version is centered around the fictional city of Hamunaptra, the “City of the Dead,” in 1926 — 4 years after Carter found Tut’s tomb. To avoid messy discussions about American involvement in the Middle East, the film’s hero, Rick O’Connell (Brendan Fraser) is introduced as an opportunistic mercenary with little moral compass fighting alongside the French Foreign Legion in an unspecified skirmish possibly associated with the Rif War.

Rick isn’t interested in treasure, colonialism, or curses. He’s dragged along by the half-Egyptian Evelyn (Rachel Weisz in the Helen role), effectively proving that nothing good can be found in the country outside of “sand and blood.” O’Connell’s motivations are more altruistic than those of his American compatriots, Henderson, Daniels, and Burns, who venture to Hamunaptra for treasure. Sucked of their life force by Imhotep, they act as symbols of what the ‘32 film was talking about — interacting with the exotic foreign, whether for prestige or wealth, doesn’t end well.

By 1999, American’s interactions with the Middle East were diverse and complicated. President Clinton had just engaged in a bombing of Iraq the year prior; the Egyptian Islamic Jihad bombed several U.S. embassies and brought to power Osama Bin-Laden and al-Qaeda; and Saudi princes were being trotted out as glamorous figures of untold wealth and intrigue.

It’s this latter comparison that factors into how the ‘99 film plays on the sexual compulsion of its monstrous figure. Ardeth Bey in ‘32 retains a crusty, weathered, clay-like visage, and audiences, who knew of Karloff in Frankenstein, aren’t quick to see him as a sex object. In contrast, Arnold Vosloo’s shirtless Imhotep is presented as erotic and enticing. The film opens with his forbidden relationship with Anck Su Namun, acting as both romantic catalyst and illustrating the character’s seductive qualities. Unlike the creepy, vampiric Ardeth Bey, Imhotep has a face that’s meant to compel the audience, blinding them to his deviousness, drawing America back to the allure of foreign others.

And thus we arrive at the 2017 installation. Creating a completely new story unassociated with Ardeth Bey or Imhotep, Alex Kurtzman’s Mummy’s main claim to fame is a female monster called Ahmanet (Sofia Boutella). Ahmanet is meant to be pharaoh until the birth of a little brother usurps her power. Hmm, a female leader’s whose shoo-in status is undermined by the birth of a privileged little boy? Nope, can’t see how that’s political at all.

Other than the ill-timed storyline, Ahmanet’s power strictly lies in seducing a man and embodying him with the power of Set to make him a “living god.” Where Imhotep in ‘99 was the literal embodiment of God bringing about the plagues of Egypt, Ahmanet — supposedly so mad about losing her power to a man — is more than willing to give it away in the hope of turning one into a god. Without spoiling the end, the mummy in this incarnation is nothing more than a catalyst for white male exceptionalism. Where the previous usages of this were invoked to shy away from involvement in foreign skirmishes, this breed of exceptionalism actively seeks to find more.

This is because the 2017 Mummy feels strictly American. Where the previous two films saw British leads co-exist alongside Americans, Tom Cruise’s Nick Morton is profoundly the lead, carrying on any future installments. Morton doesn’t want to be labeled a looter and calls himself a “liberator,” rhetoric often heard when bringing democracy to foreign nations. Morton is a modern-day cowboy, using a gun and his fists to get the plot moving. He’s also highly invested in his sexual prowess, with a running gag about his one-night stand with the film’s “girl,” Jenny (Annabelle Wallis).

Karloff and Vosloo’s sexuality was tied to their foreignness and body, respectively; Nick Morton is the all-American boy. Shown as capable, athletic, and indestructible, he’s the living embodiment of the American male who can save us all from those pesky foreign invaders who seek to do us harm. Nope, can’t think where that’s political in the least! Where Ardeth Bey and Imhotep were allowed to be both vicious and lovesick, Ahmanet is a vengeful hellbitch, an ancient Egyptian Alex Forrest looking for a bunny to boil.

The Mummy as a franchise hasn’t seen the massive resurgence in comparison to Dracula and Frankenstein because of our wobbly relationship with its central locale. In 2017, The Mummy ends up showing the mean-spirited, “America f*** yeah” attitude that’s just growing tired.

Kristen Lopez lives under a curse in Sacramento.