In a review of Elvis Presley’s Las Vegas show for Rolling Stone, journalist-cum-impresario Jon Landau noted that “no matter how frustrating the lapses in his career have been, he remains an artist, an American artist, who we should be proud to claim as our own.” More than an artist, Elvis was a prism that absorbed the best and worst of 20th-century American culture—the hard work that led to his out-of-nowhere success and his virtuosic, versatile talent, but also the excesses that claimed him—and reflected them back to anyone who had an opinion about him.

Baz Luhrmann has drawn up the standard rich and famous biopic for his magnum opus Elvis, but Elvis is best served by documentaries. Seeing the King develop into his persona and come into command of different media allows viewers to appreciate how far he traveled over the course of his career. His talent and his raw charisma remain compelling to contemporary viewers, and the perspectives of fans, detractors, and historians allow viewers to understand how great Elvis’s reach was— and the ways he touched countless lives, for good and for ill. Over the past 50 years, a series of filmmakers have directed documentaries on Elvis’s rise and fall, and longtime fans and newcomers alike will find something to appreciate in each of them.

The 1970 concert film Elvis: That’s the Way It Is finds Presley at the beginning of the end of his career. After Presley completed his final feature film under contract with MGM and shot the landmark ’68 Comeback Special, his manager, Col. Tom Parker, booked him into a four-week engagement at the International Hotel in Las Vegas. In the live footage that comprises the second half of the film, Presley has settled on the rhinestone-encrusted jumpsuit and gold aviators look that would become his late-career trademark, and his set list of country and gospel songs performed with full, ambitious arrangements play like a greatest-hits track list from his 1970s albums.

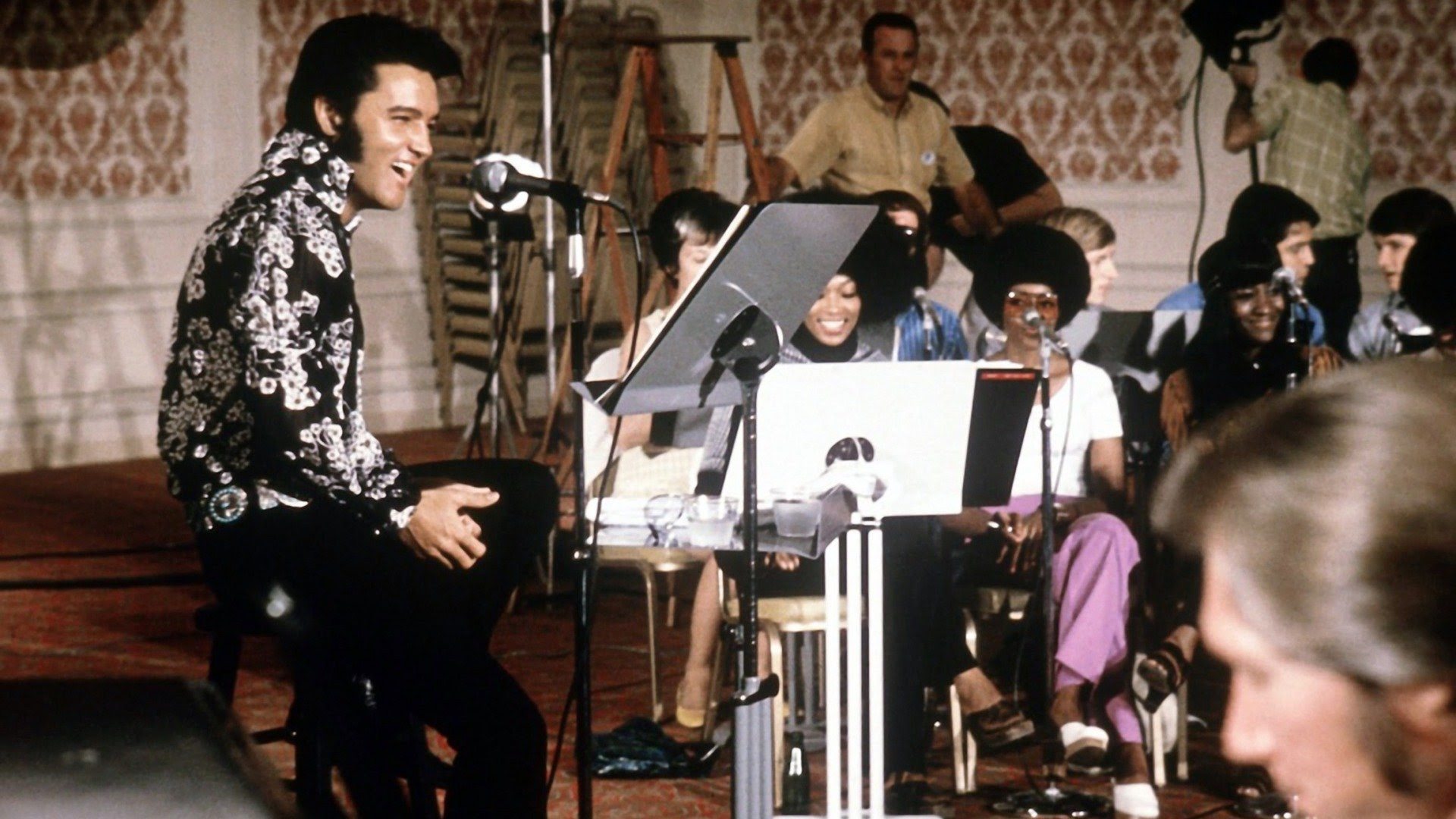

In addition to the live footage, director Denis Johnson shows viewers all the work that goes into putting on an Elvis Presley show. Watching Presley and the TCB Band go from assembling the set list and running through the songs to perfect their performance, to hearing them perform the final versions onstage in Vegas feels a little like watching time-lapse photography. The loose framing and shot composition give the rehearsal footage a sense of immediacy, but also undercuts the spontaneity of the live performance, as when Presley rehearses the stage patter that precedes “Polk Salad Annie”. A quick shot of Presley ably playing through a hymn on the piano also shows skeptical viewers that he was had the ability to be a credible musician, in addition to being a one-time teen idol and a magnetic screen presence.

Johnson and editor Henry Berman intercut the rehearsal footage with B-roll of hotel staff hanging signs, decorating the lobby, and stocking the hotel store with Elvis merch, showing audiences all the work it took to put on a show of this size. A series of interviews with his many fans gives viewers an idea of where Elvis fandom was at the end of the 1960s. While the heartfelt interview with a clergyman is the most surprising clip, a chat with two girls in their 20s who had grown up listening to Elvis is probably the most relatable. Their calm presence and straightforward explanations for their love of the King contradicts what we think we know about fangirls, and one of the girls’ confession that “I love Elvis the way I would love my siblings” sounds strangely endearing in context.

Released five years after Presley’s untimely death, This Is Elvis serves as a visual scrapbook that walks audiences through his life and his groundbreaking career. Directors Malcolm Leo and Andrew Solt drew on a treasure trove of never-before-seen home movies and behind-the-scenes footage from his movie appearances, which they intercut with re-enactments and scenes from his movies and concert tours. While the archival footage was a huge draw for Elvis fans who were still missing their king, This Is Elvis also served as a solid starting point for potential new fans to see Elvis in action and to understand the arc of his career and his impact on popular culture. This was the best source to see his early TV performances, and seeing him in his handsome, youthful glory must have been especially shocking after the endless coverage of his late-in-life performances.

By today’s standards, This Is Elvis offers a sugar-coated look at Presley’s career. Leo and Solt avoid any controversial topics, like the accusations of racism against the singer, his prescription drug abuse, and the circumstances under which he met Priscilla. The hagiographic tone comes out in other ways as well; the reenactments of Elvis’s childhood look like something out of a late-1970s live-action Disney movie like The Apple Dumpling Gang, and Leo and Solt’s narration can get overwrought, especially when they imagine what their subject would be saying from beyond the grave.

Many depictions of Presley’s early career can gloss over the extreme poverty he experienced in his formative years. The Burger and The King, Dave Marsh’s 1993 documentary about the food Elvis ate and the role of food in his life, puts the hardship he experienced in a very specific perspective that almost any viewer would understand. As a group of hunters walks through a wooded area in Tupelo, Mississippi—about three miles from where the King grew up—an intertitle pops up reading “Back in the Depression, you’d eat anything that didn’t eat you…” and a local historian talks about squirrel hunting. That detail, combined with some shots of the Elvis Presley Birthplace in Tupelo, drives home the point of how far Elvis had to go to take on the era-defining role he would assume.

Jokes about Elvis’s weight and his appetite for peanut butter-and-banana sandwiches were low-hanging fruit starting from the time he died, and Marsh punctuates The Burger and The King with quirky visuals (like the tableaux that opens the movie of Elvis impersonators tucking into a candlelit meal of hamburgers). Because Marsh focuses on one aspect of life that viewers share with Elvis—appetite and a need for food—his depiction of The King is more relatable than the previous films. He’s able to look at the roles race, class, and religion played in forming Elvis’s public image and his relationship with the world around him through food; a scene early in the film, in which soul food cook Jean Sims talks about the significance of soul food in the Black church, says a lot about Elvis’s relationship with the Black community in Tupelo. Though Elvis’s appetite for rich food was seen at best as an amusing quirk and at worst a cruel punchline, an observation from his cook, Mary Jenkins, gives his diet a poignant quality: “He said that’s the only thing he got any enjoyment out of, eating.”

Eugene Jarecki’s 2017 documentary The King expands upon the scrapbook approach from This Is Elvis, taking Presley’s 1963 Rolls Royce Phantom V on an epic road trip to learn about Presley’s life and legacy. Jarecki and his three cinematographers establish an appropriately gaudy visual style from the first frame; low-angled shots of light-up signs on the Vegas strip against the night sky evoke velvet-painted portraits of Elvis in his 1970s rhinestone finery, and the contrast between the beautiful, mostly well-maintained car and some of the lower-income neighborhoods it drives through serves as an elegant metaphor for Presley’s upward class mobility.

Jarecki draws parallels between 20th century mass media and Elvis’s public life with the political and social problems that divide American citizens in the 21st century. This idea works especially well in an interview with Van Jones, who eloquently explains the harm Elvis did to Black musicians when he appropriated their music without credit only to not get involved with the civil rights movement. Jarecki’s extensive use of montage-style editing is effective in smaller, more pointed doses—as in a short scene where he runs audio from a Trump rally under a video of Elvis onstage in Vegas—but his reliance on this technique gets more heavy-handed as the film progresses. The closing montage of horrors such as the fall of the World Trade Center, the OJ Simpson trial, and the bombing of Iraq cut to Elvis’s performance of “Unchained Melody” is numbing when it was probably intended as cathartic.

The two-part HBO documentary Elvis Presley: The Searcher is more satisfying because it treats Elvis as a musician first and foremost. Instead of interviewing a wide swath of people who have little to nothing to do with music, director Thom Zimmy speaks with Emmylou Harris, Tom Petty, Robbie Robertson, and Bruce Springsteen—as well as with several sources who knew Elvis throughout his lifetime—to foreground Elvis’s significance in revolutionizing rock and roll and making it accessible to a more mainstream audience.

The focus on Elvis’s musicianship instead of his celebrity brings insights to the fore that might surprise non-fans and inspire them to take another listen to his music. Bones Howe, who appeared with Presley in the 1968 comeback special, spoke of how Elvis worked with RCA engineer Steve Sholes to get the stripped-back, reverb-heavy sound of his early records with the label. Another scene in the film about Elvis’s recording of “It’s Now or Never” spotlights how skilled he was as a vocalist, and how he adapted the challenging melody of an operatic standard to his style and his vocal ability.

Compared to the fast editing and flashy visuals of The King, Elvis Presley: The Searcher has a hushed quality. Luke Geissbuhler’s wide shots of Graceland’s interiors, shot in natural light with a subdued palette, evoke William Eggleston’s photography, and give the audience a beat to absorb the stories they’re hearing about the King. All of the interviews are presented as voiceovers, which puts the focus on their words and not on the personality speaking them. The overall effect of this subdued approach to its subject allows viewers the opportunity to see Elvis Presley beyond his rhinestone-encrusted trappings and understand his artistry and significance.

There’s no one story behind an artist as visionary as Elvis. While Baz Luhrmann’s biopic will undoubtedly introduce a new audience to his work, these documentaries will deepen viewers’ knowledge and give them new ways of understanding Elvis Presley.