The greatest rock ‘n roll documentary ever made isn’t a real documentary. And it’s not about a real band. Rob Reiner’s This is Spinal Tap is a raucously funny and often terribly sad chronicle of a mediocre British rock group’s slide into irrelevance. Poking merciless fun at the self-important music docs of the era, it’s a boomer hagiography in reverse. The eponymous cock-rockers started out as Beatles wannabes, moved into hippy-dippy territory for a while before (big) bottoming out in the unforgiving world of heavy metal. Reiner plays a documentarian tagging along for what looks like it will be the band’s final tour, downsizing from arenas to air force bases and theme parks where they’re second billed to puppet shows. It’s the end of an error, the twilight of the dolts.

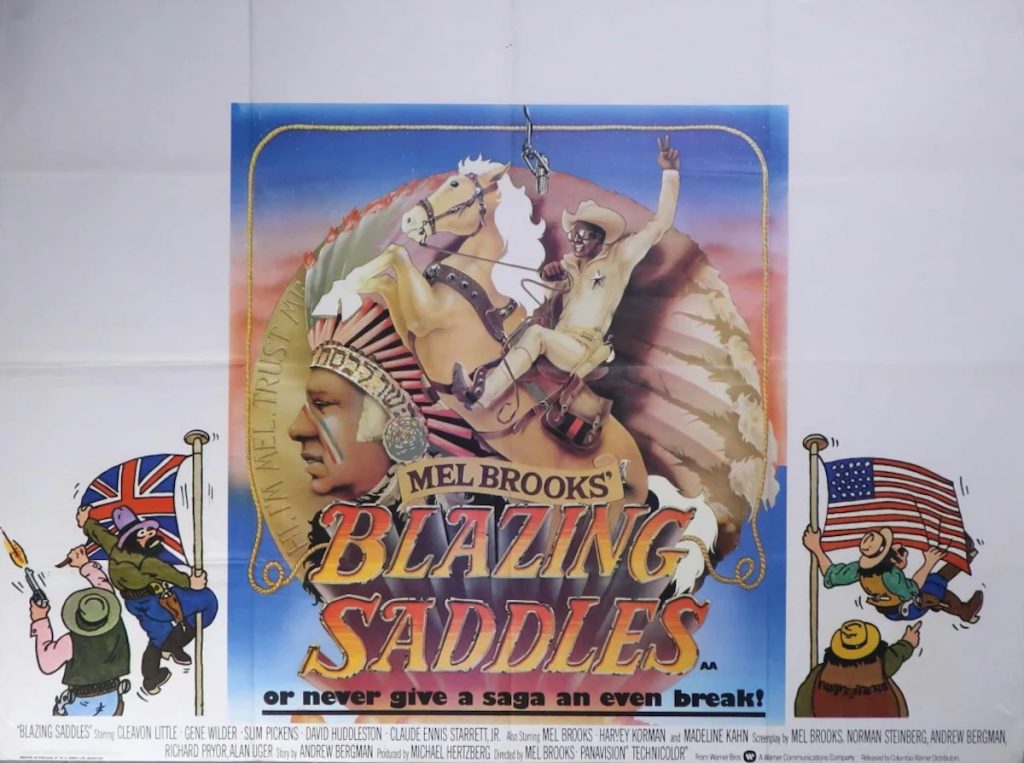

Spinal Tap was by no means the first mockumentary, but one could make a case for it being the most influential. The form has become a genre of its own now, with seemingly half of post-Office sitcoms adopting the format. Yet what confounded audiences four decades ago is that the parody here is played completely straight. Nobody ever keys you in that you’re watching a comedy. This is Spinal Tap was initially advertised with a crude cartoon of a guitar’s neck tied into a knot, shamelessly aping the poster for Airplane! and suggesting similar satirical hijinks involving “one of England’s loudest bands.” Spinal Tap is as funny as Airplane! – probably funnier – but in an entirely different register.

Reiner conceived the movie with pals Christopher Guest, Michael McKean and Harry Shearer. The fake band was born in a comedy sketch on an unaired pilot directed by Reiner in 1978, then the following year Guest played guitar under the name Nigel Tufnel on McKean and David Lander’s Laverne and Shirley tie-in novelty album, Lenny and the Squigtones. The friends fooled around for years, coming up with a complex saga for Spinal Tap. Accomplished musicians all, they also wrote some brilliantly stupid songs. What they couldn’t quite lick was a screenplay.

Given $60,000 by British TV mogul Lew Grade to write a script, the crew instead shot a 40-minute short covering all the story’s salient points, filling out the dialogue with their own improvisations. Spinal Tap: The Final Tour was completed in 1981 and rejected not just by Grade, but also every other studio in town. The widely circulated tape, meanwhile, became the stuff of underground comedy legend. (Producer Karen Murphy claims there was a copy found in the room where John Belushi died at the Chateau Marmont.)

Eventually, the boys got the backing of Norman Lear’s Avco-Embassy Pictures, and they shot the movie as if it were an actual rock documentary, even hiring cinematographer Peter Smokler, who had been a cameraman on Gimme Shelter and Jimi Plays Berkley. Working from a 40 page outline, the actors all improvised their dialogue, miraculously playing it ramrod straight while delivering some of the most iconically idiotic lines in movie history. (“This one goes to eleven,” etc.) So complete is the cast’s commitment that Smokler later said he didn’t understand what was supposed to be funny about the movie while he was filming it.

I first watched and recorded the film when my local PBS affiliate played it in the late night Saturday slot where they used to show cool cult movies like Spinal Tap and Swimming to Cambodia. It soon became a game that my high school stoner friends and I liked to play, springing Spinal Tap on people and pretending it was real. If you could distract them during Billy Crystal’s cameo as a miserable mime, the film didn’t feature any other faces recognizable enough to teens at the beginning of the ‘90s that would shatter the illusion. The film’s verisimilitude is awfully convincing, especially when watching it with weed. I remember it took one acquaintance all the way up to the part where the band gets lost, wandering the hallways of the Cleveland arena trying to find the stage, before he finally cough-laughed a giant cloud and said, “Dude, these guys are idiots.” (Last I heard, that fellow was working on a nuclear submarine. So I feel safe.)

Sting famously said that he didn’t know whether to laugh or cry while watching This is Spinal Tap. Steven Tyler was quoted as saying he didn’t find it funny at all, perhaps because Aerosmith’s 1982 album Rock and a Hard Place had a picture of Stonehenge on the cover, though notably not one in danger of being trod upon by a dwarf. The band’s falling fortunes are undeniably hysterical, but it’s never a mean-spirited movie.

The boys are far less sleazy and destructive than their real-life counterparts we meet in, say, The Decline of Western Civilization II: The Metal Years (to name another VHS staple of the era.) Their stupidity is endearingly child-like, especially Guest’s wide-eyed, gum-chomping Nigel, hurt and left out by his preening pal David St. Hubbins (McKean, nailing a lead singer’s naturally aristocratic airs) bringing his girlfriend on the road. Shearer’s Derek Smalls –the bassist who stuffs his pants with foil-wrapped cucumbers– always appears quite confidently aware of about 60% of what’s going on around him.

The film’s more sordid aspects were left on the cutting room floor. There’s a famous, nearly four-hour rough cut of Spinal Tap that’s long been floating around bootleg conventions and later the internet, an assembly of all the individual location scenes in all their rambling, original form. (Reiner shot another three hours of interviews with the band to use as glue.) Naked groupies and drugs abound, as do abandoned subplots. We learn the sad family history behind Billy Crystal’s mime catering service “Shut Up and Eat,” before finding out that the source of all those herpes sores we keep seeing are an opening act played by The Runaways’ Cherie Currie. Most famously, there’s a sequence in which the band gets Bruno Kirby’s Sinatra-worshiping limo driver stoned out of his gourd, until he’s singing the Chairman’s “All the Way” in his underwear. (Renier had previously made a short film with Kirby about the character called “Tommy Rispoli: The Man and His Music.”)

It’s not easy sitting through longer versions of all these scenes. One can understand why Smokler didn’t think it was very funny while he was filming them. The actors are playing everything so straight and adhering to the film’s reality with such immersive discipline, one acclimates to their fundamental absurdity and the film almost feels like a drama. (When the bootleg first started kicking around, I remember hearing this longer version referred to as “the dramatic cut.”) What becomes even more impressive in hindsight is how editors Kent Beyda and Kim Secrist were able to sift through this mountain of footage and pull exactly the right jokes and just enough story to keep it propulsive. At 82 minutes, the release version of This is Spinal Tap is a marvel of compression and concision. The movie moves.

The film is getting a “41st anniversary” theatrical re-release this month and a revamped Criterion Collection disc is on the way, in preparation for a sequel that’s supposed to be arriving in the fall. This is worrisome for several reasons, foremost that the previous Spinal Tap reunion albums, 1992’s “Break Like the Wind” and 2009’s “Back from the Dead,” were depressingly lame affairs, while there are few talented directors who have un-learned how to make a movie quite as egregiously as Rob Reiner. (Seriously, what happened with that guy? Like five or six beloved classics straight out of the gate and then nothing but dreck thereafter. He hasn’t made a watchable movie since Bill Clinton was president.)

Hollywood in general has embraced Spinal Tap’s improvisatory methods but not the crew’s ruthless discipline in the cutting room. The Judd Apatow era gave us a lot of 125-minute comedies where everyone stands around making up jokes. (One grieves for the art of editing when you’re on ending number 14 of The Big Sick.) Guest kept the torch going for a while by directing a string of improv comedies featuring members of the Tap troupe, but those films got progressively baggier and more sentimental to a point where I don’t think I know anyone who watched 2016’s Mascots, and if they did they never mentioned it.

Maybe Spinal Tap would have been off staying a secret handshake for headbangers and comedy nerds, something passed along via bootlegs and odd-hour PBS screenings. Like the commercial for their fictional 1984 greatest hits album said, “Heavy metal memories last forever, but at this special price they can’t last long.”

“This is Spinal Tap”‘s “Golden 41st Anniversary 4K restoration” plays in theaters for three days only, starting July 5, through Fathom Events. More info here.