What would make a “good” documentary about America’s gun culture? What could reveal something new, or convince someone to change their beliefs? Can such a deadly serious subject only be represented in a sober, unobtrusive, verité style? Or is a more provocative voice of righteous anger needed to upset our growing complacency?

The notoriously provocative Michael Moore veered toward the latter approach twenty years ago with Bowling for Columbine, part investigation and part angry screed. Moore was responding to the school shooting at Columbine High School in Colorado in 1999, where two disgruntled, heavily armed boys killed 12 of their fellow students before dying by suicide. The massacre spurred copycat incidents, and today is often referenced as the Patient Zero of our current epidemic of school shootings.

Given this material, it’s impossible, at this moment, to fully engage with the film before processing those intense, tangled emotions this subject now stirs in us: the horrible numbness mixed with roaring sorrow and rage. As Moore follows the aftermath of Columbine, things are, horrifyingly, the same as they ever were: the images of the parents of Columbine victims protesting, the conferences that the NRA refuses to relocate in the wake of violent tragedies, and the parents’ desperate pleas for bans on assault weapons are relentless patterns in our current everyday life.

Because of both his style of montage (with satirical uses of sunny found footage and ironic juxtapositions between sound and image) and his on-camera confrontations with the powers that be, Moore has often been seen as a hacky doctrinaire. Though Moore comes into Bowling (as he does with all of his movies) with a particular point of view on America and what ails it, he plays fair. In one segment, he takes a trip to Canada – also a country with many guns, but low rates of gun violence. His series of interviews with sunny Canadians stating that they don’t even lock their doors is a deceptively jolly pivot back to Moore’s true, challenging question: what is it exactly about America that breeds this thirst for violence?

Though he loves taking aim at specific, powerful targets, Moore uses different techniques to explore this thorny, maddingly elusive question. He doesn’t cheat, acknowledging the intangibles and imponderables of the question as he explores the darker recesses of the American psyche. And he goes to all the right places, exploring the roots of domestic terrorism when interviewing Michigan militia men (and some women, whose babies idly crawl around their firearms). One of the most chilling interludes is Moore’s conversation with James Nichols, the brother of Terry Nichols, the domestic terrorist convicted of participating in the Oklahoma City bombing. Nichols is a man with a terrifying persecution complex, easily flat-footed by Moore’s challenging questions but incapable of shifting his beliefs. He also looks at the aimless young men of his home state, Michigan, who seem to turn to stealing guns and making bombs, as a sort of vague expression of disgruntlement at the way institutions have written them off.

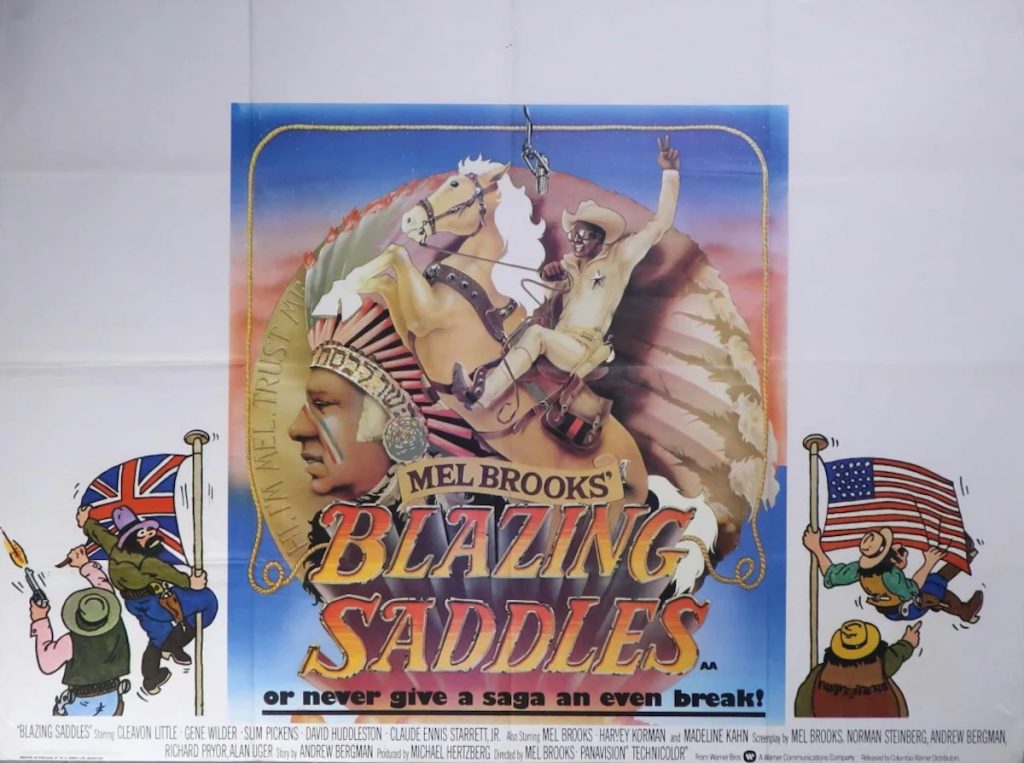

Moore was most prophetic in identifying race and racism as important aspects of the gun problem. He notes that fear of violent black bogeymen, often stoked by the media, have long helped to boost gun sales. He tells this story crudely, as a cartoon reminiscent of South Park tells the story from slavery to white flight as one important strain of the love of guns. It’s simplistic and perhaps offensively cheesy. This is Moore’s other side: he’s both the traveling investigator and the cynical, angry activist using the medium of film to mock and call out.

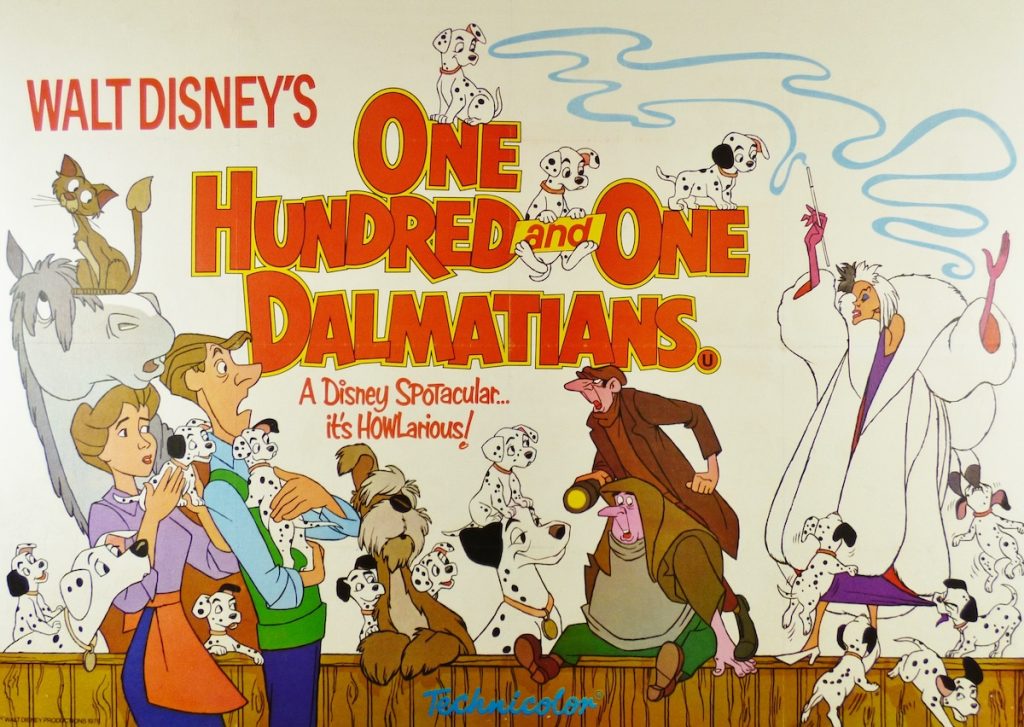

His most controversial moves are the brutal montage sequences set to happy music. Moore’s out looking for the Big Bad behind all the things that are corroding America. One of his grand theories is that America’s gun culture is tied to American foreign policy that plays kingmaker in countries all over the world with little care for the massive death tolls they leave in their wake. A montage set to Louis Armstrong’s “What a Wonderful World” reveals the sickening carnage left behind by American intervention makes a case, but still feels slightly derivative and disconnected from the rest of the film. Moore is more at home with direct confrontations with the powerful and complicit, as when he shows K-Mart executives the bullets stuck in the bodies of Columbine survivors. It’s also schlocky (and perhaps exploitative), but it reflects Moore’s authentic belief that shame and confrontation can enact change.

You don’t get to be a big of a cynic as Moore often appears without having been a romantic. There’s no doubt Moore has a romantic vision of (perhaps lost) America that lets the working class survive and thrive. The ability to appreciate Bowling for Columbine two decades on may depend on how much you can believe that dream is still alive.

“Bowling for Columbine” is streaming on several ad-supported services.