Human beings have a natural fear of animal attacks, a fear that horror movies have exploited since cinema began. At first they tended to be extinct or exaggerated animals (think King Kong); then the Atomic Age introduced the idea of real animals made huge by radiation. It was Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) that grounded the animal-attack movie, keeping the outrageous nature of the attacks but letting the threat be as close to real life as possible.

The enormous success of that film reverberated throughout the next few decades, and while there were some satiric imitators (notably 1978’s Piranha), most Jaws rip-offs attempted a similar serious tone, in spite of many of the films delving into unintentional camp (including the Jaws sequels themselves). Nonetheless, Jaws helped the horror film in general become more mainstream, and the increasing popularity of the genre led to 1996’s Scream, which acknowledged horror’s popularity (particularly the slasher film) by deconstructing and commenting on its common tropes.

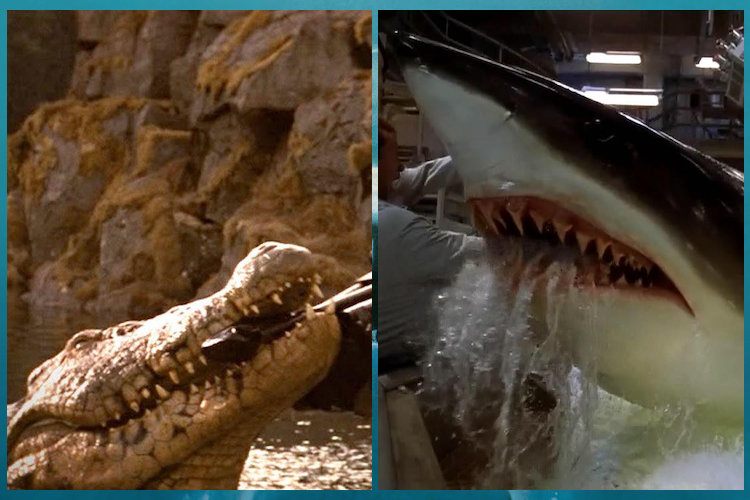

It’s in the wake of that milestone that, in July 1999, two animal-attack horror films were released that did for their sub-genre what Scream had done for the slasher: Lake Placid and Deep Blue Sea. While neither movie had as large a cultural impact as other game-changing horror films, they broke convention and challenged tropes enough that they still stand as a template for the modern animal-attack movie two decades later.

One of the biggest ways both films subvert the standard animal-attack movie is in their treatment of their antagonists. Deep Blue Sea began life as yet another killer shark film, and in the bulk of those movies the sharks were vilified while the human protagonists were seen as paragons of determination and resilience. Deep doesn’t necessarily de-vilify its shark antagonists, but they feel much less loathsome thanks to the human protagonists being portrayed as selfish, short-sighted, arrogant, and weak. Dr. Susan McAlester’s (Saffron Burrows) plan to cure Alzheimer’s by creating super-intelligent sharks in order to extract proteins from their highly developed brains is portrayed as a transgression akin to Victor Frankenstein’s, an affront to nature that cannot be forgiven. Most of the rest of her colleagues each have their own hang-ups, and as a result become shark bait. In their deaths, the film certainly doesn’t blame the sharks.

Meanwhile, Lake Placid builds on that kindness toward the attacking creature and becomes a full-fledged animal activist story. In the movie, the authorities of Aroostook County in Maine discover that a 30-foot crocodile has managed to find its way into the local lake, and has found a taste for humans. It turns out that eccentric citizen Delores Bickerman (Betty White) has been regularly feeding the croc for several years, and has much more affection for it than for any of her fellow humans (“I’m rooting for the crocodile,” she says pointedly). The film not only backs her point of view, showing the majority of the authority figures in charge of stopping the crocodile’s feeding frenzy to be obnoxious, snooty, petty, and overall self-involved, but over the course of the movie has these characters agreeing that the giant croc should be caught and transported away rather than killed. For a film that begins with a vicious and cruel murder perpetrated by the crocodile, it’s a rather bold and surprising turn of events. In both movies, the attacking animal is not to be reviled — Placid sees the human characters turning contrite and helping their attacker, while Deep makes it clear that any evil in the film is the result of Man’s meddling.

Meanwhile, Lake Placid builds on that kindness toward the attacking creature and becomes a full-fledged animal activist story. In the movie, the authorities of Aroostook County in Maine discover that a 30-foot crocodile has managed to find its way into the local lake, and has found a taste for humans. It turns out that eccentric citizen Delores Bickerman (Betty White) has been regularly feeding the croc for several years, and has much more affection for it than for any of her fellow humans (“I’m rooting for the crocodile,” she says pointedly). The film not only backs her point of view, showing the majority of the authority figures in charge of stopping the crocodile’s feeding frenzy to be obnoxious, snooty, petty, and overall self-involved, but over the course of the movie has these characters agreeing that the giant croc should be caught and transported away rather than killed. For a film that begins with a vicious and cruel murder perpetrated by the crocodile, it’s a rather bold and surprising turn of events. In both movies, the attacking animal is not to be reviled — Placid sees the human characters turning contrite and helping their attacker, while Deep makes it clear that any evil in the film is the result of Man’s meddling.

In deviating so far from the norm of what had been the animal horror movie up to that point, both Lake Placid and Deep Blue Sea might have been less well received were it not for their knowing and clever use of humor. The humor in Deep is, for the most part, the standard quippy dialogue that could be found in any action film at the time. Yet there are comedic moments that go hand-in-hand with the film’s rule-breaking spirit. Most of these moments involve the character of Preach (LL Cool J), who for two-thirds of the film is separated from the main cast, having to undergo his own trials and tribulations with the invading sharks. One set-piece sees Preach trapped in his flooded kitchen, hiding inside his oven, when the attacking shark hits the dials with its nose, which turns the oven on. Later, Preach has a line of dialogue that seems like it could’ve been lifted directly from the meta Scream, where he observes that “brothers never make it out of situations like this! Not ever!” That Preach is ultimately one of the last survivors of the movie is part and parcel of its subversive nature, and it’s in the question of who lives and who dies that the movie finds a sort of Grand Guignol humor as well.

In deviating so far from the norm of what had been the animal horror movie up to that point, both Lake Placid and Deep Blue Sea might have been less well received were it not for their knowing and clever use of humor. The humor in Deep is, for the most part, the standard quippy dialogue that could be found in any action film at the time. Yet there are comedic moments that go hand-in-hand with the film’s rule-breaking spirit. Most of these moments involve the character of Preach (LL Cool J), who for two-thirds of the film is separated from the main cast, having to undergo his own trials and tribulations with the invading sharks. One set-piece sees Preach trapped in his flooded kitchen, hiding inside his oven, when the attacking shark hits the dials with its nose, which turns the oven on. Later, Preach has a line of dialogue that seems like it could’ve been lifted directly from the meta Scream, where he observes that “brothers never make it out of situations like this! Not ever!” That Preach is ultimately one of the last survivors of the movie is part and parcel of its subversive nature, and it’s in the question of who lives and who dies that the movie finds a sort of Grand Guignol humor as well.

If Deep is a clever horror movie with some meta-textual humor, then Placid is a screwball farce with some horrific elements. Screenwriter David E. Kelley keeps a general thriller structure to the movie, but his strength in writing for sitcoms and other comedically focused work is predominant. The Howard Hawks-ian nature of the leading characters, with their bickering, rapid-fire dialogue punctuated by wry non sequiturs and knowing quips (“I just have this feeling that everything’s totally safe,” says Brendan Gleeson’s sheriff at a tense moment) makes it feel like the film could be successfully mounted as a stage production. Placid is one of the most genuinely funny horror comedies ever made, mostly for the fact that the film strikes a balance between the two where one doesn’t ultimately get sacrificed for the other.

Both films have an inherent glee about them, and that tone likely comes from the excitement the filmmakers had at breaking as many tropes and rules as they could. Placid has fun flipping the adventure movie archetypes Jaws utilized on their heads — in this movie, the sheriff is a grumpy brute, the scientific expert (Bridget Fonda) is judgmental, easily scared, and inexperienced, and the great animal hunter (Oliver Platt) is hedonistic and irresponsible. It’s why it becomes such a perfect payoff when the movie reveals that it’s not building to an action/adventure ending, but rather a conservationist one, with the third act “battle” being about capturing the croc.

Placid cleverly plays with the audience, while Deep sadistically gooses them, pulling the rug out from under the audience every chance it gets. The film’s most famous scene sees Samuel L. Jackson’s character Russell Franklin, a wealthy, natural leader who’s survived an avalanche disaster in his past, give a rousing, inspirational monologue that is a literal showstopper. The film takes great care to showcase the speech, milking it for all it’s worth, when suddenly one of the sharks jumps up out of the water and chomps down on Russell, dragging him into the ocean and sharing his carcass with another shark. Nearly every death in the movie is played for a shock like that, none of them telegraphed or foreshadowed, up to and including Dr. McAlester’s death at the end of the movie. Like any good horror film, these choices were made to keep the audience off balance, by breaking formulas and structures that had formed naturally over the years.

When Lake Placid and Deep Blue Sea were released within weeks of each other in July 1999, it was likely due to the weird synchronicity that happens in Hollywood every so often. However, in hindsight the timing couldn’t have been more perfect, as the two films taken together signaled the end of the prototypical animal-attack horror movie while forging a path for them that has continued to this day. Films like The Shallows (2016), 47 Meters Down (2017) and its upcoming sequel, The Meg (2018), last week’s Crawl, not to mention the glut of direct-to-video and SyFy Original sequels to Placid and Deep themselves — they all owe a debt to these movies. Like Placid advocated for, the sub-genre was preserved, but like Deep warned of, these monsters, once set free of their formulaic ways, can no longer be contained.