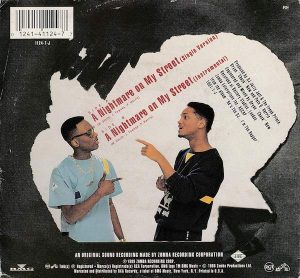

In the spring of 1988, DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince released the album He’s the DJ, I’m the Rapper, featuring the single “Parents Just Don’t Understand,” a massive hit that would go on to win the first-ever Grammy for best rap performance. The album’s next single was to be “A Nightmare on My Street,” an ode to Freddy Krueger inspired by the three A Nightmare on Elm Street films. Part 4, The Dream Master, was due at the end of the summer, and the Fresh Prince — aka future A-lister Will Smith — and Jazzy Jeff approached New Line Cinema about including the song on the soundtrack. New Line couldn’t come to a financial agreement with the record label and commissioned The Fat Boys to contribute a rap song instead, but Jeff and Fresh Prince released their single anyway, even going so far as to shoot a music video (which actually aired on MTV before New Line sued to make it disappear). “A Nightmare on My Street” reached #15 on the Billboard charts at the same time The Dream Master was in theaters. And thus it came to be that one of the biggest stars in the world owes some of his early success to Freddy Krueger.

In the spring of 1988, DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince released the album He’s the DJ, I’m the Rapper, featuring the single “Parents Just Don’t Understand,” a massive hit that would go on to win the first-ever Grammy for best rap performance. The album’s next single was to be “A Nightmare on My Street,” an ode to Freddy Krueger inspired by the three A Nightmare on Elm Street films. Part 4, The Dream Master, was due at the end of the summer, and the Fresh Prince — aka future A-lister Will Smith — and Jazzy Jeff approached New Line Cinema about including the song on the soundtrack. New Line couldn’t come to a financial agreement with the record label and commissioned The Fat Boys to contribute a rap song instead, but Jeff and Fresh Prince released their single anyway, even going so far as to shoot a music video (which actually aired on MTV before New Line sued to make it disappear). “A Nightmare on My Street” reached #15 on the Billboard charts at the same time The Dream Master was in theaters. And thus it came to be that one of the biggest stars in the world owes some of his early success to Freddy Krueger.

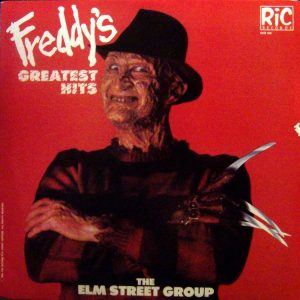

The original Freddy film, A Nightmare on Elm Street, was a mere four years old in 1988, but in that time the character had gone from an obscure independent horror movie villain to one of the most recognizable icons in the world. It was one thing for Freddy to be popular on movie screens, as the Nightmare films continued to rake in large amounts of money over comparatively small budgets (such that fledgling New Line Cinema would later refer to itself as “the house that Freddy built”). It was quite another to have the character appear in Halloween costume shops, on T-shirts and action figures (both bootleg and, in 1989, official), in comic books (published by Marvel, no less), tie-in novels, a 1-900 entertainment phone line, music videos, and records (including an appearance in that Fat Boys song). Not just mainstream pop/rock/rap hits, either, but novelty records, too—the album Freddy’s Greatest Hits, released in 1987 by “The Elm Street Group,” is a collection of covers and original songs with the occasional vocal contribution of Robert Englund, the actor who originated the character. That such an album even existed is testament to Freddy’s popularity, and is reminiscent of similar kitschy tie-in records such as “Christmas in the Stars,” featuring R2-D2 C-3PO from Star Wars. In fact, the closest thing at the time to Freddy’s widespread popularity and recognizability as an original, made-for-the-movies villain would have to be Star Wars’ Darth Vader.

The original Freddy film, A Nightmare on Elm Street, was a mere four years old in 1988, but in that time the character had gone from an obscure independent horror movie villain to one of the most recognizable icons in the world. It was one thing for Freddy to be popular on movie screens, as the Nightmare films continued to rake in large amounts of money over comparatively small budgets (such that fledgling New Line Cinema would later refer to itself as “the house that Freddy built”). It was quite another to have the character appear in Halloween costume shops, on T-shirts and action figures (both bootleg and, in 1989, official), in comic books (published by Marvel, no less), tie-in novels, a 1-900 entertainment phone line, music videos, and records (including an appearance in that Fat Boys song). Not just mainstream pop/rock/rap hits, either, but novelty records, too—the album Freddy’s Greatest Hits, released in 1987 by “The Elm Street Group,” is a collection of covers and original songs with the occasional vocal contribution of Robert Englund, the actor who originated the character. That such an album even existed is testament to Freddy’s popularity, and is reminiscent of similar kitschy tie-in records such as “Christmas in the Stars,” featuring R2-D2 C-3PO from Star Wars. In fact, the closest thing at the time to Freddy’s widespread popularity and recognizability as an original, made-for-the-movies villain would have to be Star Wars’ Darth Vader.

That leap in popularity is fairly huge when considering the character’s origins. Created by Wes Craven, the writer and director of 1984’s Nightmare, Freddy (or “Fred,” as he was credited in that film) was intended as a shadowy nightmare figure who is more talked about than seen. He has only a handful of lines of dialogue and is never shown fully lit. Craven was using the character as a representative of primal, subconscious fears (hence the razor glove, standing in for an animal’s claws), and gave him a backstory about being a “filthy child murderer” to explain his vile nature and give the Elm Street parents motivation for their morally ambiguous vigilante killing of Fred.

The second film, Freddy’s Revenge (1985), continued to use Krueger in a malicious, truly villainous manner, but the character’s popularity (as well as that of the actor who played him) was already starting to show—New Line initially refused to give Englund a raise and filmed for two weeks with a stuntman in the role of Freddy, before reconsidering after seeing the footage. When 1987’s Part 3: Dream Warriors came along, New Line and the filmmakers had stumbled upon a formula for the series, setting it apart from other horror offerings of the time by focusing on elaborate, surrealist kill sequences combined with gallows humor from Freddy. This formula worked so well that Dream Warriors was a massive box office hit, catapulting the character into the stratosphere.

That popularity can be seen immediately in Dream Master, as Englund not only gets top billing but a large amount of screen time as well. The evolution is most apparent in a nightmare sequence set on a sunny beach in which a well-lit, fully shown Freddy puts on a pair of sunglasses set to (in the original theatrical release, anyway) “a Miami Vice-like riff.” Director Renny Harlin claims that during the shooting of the scene, a large crowd of fans gathered to watch, excited to see Englund in makeup. Fred the creepy horror film monster had left, and Freddy the pop icon had arrived.

Freddy became nearly inescapable in 1988, invading just about every form of media. Not only was he in the aforementioned comics and books and being name-checked in unauthorized rap songs on the radio, but he was appearing in (authorized) music videos from the Dream Master soundtrack, in addition to straight-up hosting special blocks of MTV.

That was only the beginning, however. On Oct. 6, the Sid & Marty Kroft puppet parody show D.C. Follies featured Englund as Krueger as a special guest star, where he was a figment of George H.W. Bush’s nightmare. Two days later, Freddy’s Nightmares debuted in syndication, part of a wave of late-‘80s sci-fi/horror anthology TV shows. Its gimmick was, of course, the appearance of Englund’s Krueger in every episode. Rather than being the show’s Rod Serling, however, Krueger acted more as a ghoulish emcee in the vein of schlock horror hosts Zacherle, Svengoolie, and Elvira. In his love of terrible grisly puns and sinister commentary, Freddy the host can be seen as the precursor to the Cryptkeeper of the popular Tales from the Crypt series that began a year later.

After 1988, the Nightmare series dwindled in financial success, as Part 5: The Dream Child (1989) and Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare (1991) suffered diminishing returns; the TV series was cancelled after two seasons. Yet Freddy’s popularity didn’t dwindle — Craven even came back to the series in 1994 with New Nightmare, not so much to revive the franchise as to reconcile his original concept with the pop phenomenon it had become. Fan support for the character continued to be strong enough through the next decade that New Line, now a division of Warner Bros., produced a crossover film with another instantly recognizable ‘80s horror star — Friday the 13th’s Jason Voorhees — resulting in 2003’s Freddy Vs. Jason, a movie that was almost successful enough to start a monster mash franchise of its own.

Freddy continues to appear (albeit with less ubiquity) in comics, books, video games, and parodies to this day, and his ratty red and green sweater and razor glove can be found at every single Halloween pop-up shop each October. What’s most remarkable is that, thanks in large part to his huge popularity 30 years ago, Freddy Krueger has now joined the pantheon of characters that are recognized around the world just by a name and a silhouette. As the Springwood Slasher himself prophetically says in The Dream Master, “I am eternal.”