As he turns 65 this month, cineastes may wonder if Takashi Miike will take a break to celebrate his birthday. The legendary Japanese director has been insanely prolific, racking up well over 100 credits over the course of 30+ years. While Miike has dabbled in almost every genre – comedy, drama, kids’ flicks, crime, zombie musicals – to English-language audiences, he will forever be associated with ultra-violent horror. Films like Audition and Visitor Q redefined cinematic depravity, depicting things so graphic that the movies remain banned in several territories. Miike defined what was sold to morbidly curious Western audiences as “New Asia Extreme,” stories of body horror and moral degradation that brazenly outperformed their Hollywood contemporaries. Many copycats would try to one-up Miike with their own gore-nography, but Miike’s no-holds-barred freneticism has rarely been truly challenged. His most infamous work is the standard bearer for extreme violence and has retained its title for close to 25 years.

Ichi the Killer, released in 2001, is notoriously hard to watch. Based on a manga by Hideo Yamamoto, the film held festival screenings worldwide and offered eager audience goers barf bags just in case. The BBFC, the ratings board in the UK, demanded over three minutes of cuts before it could receive an 18 certificate. The passage of time has not quashed its disturbing nature. Viewers have not grown impervious to scenes of heat hook and hot oil torture, serial rape, and a man cutting off the top of his own pierced tongue. This is a proudly perverse piece of work but it’s also more than a series of shocks. Ichi the Killer is clear in its choices to tell a story of how violence works, both within reality and the limitations of art itself.

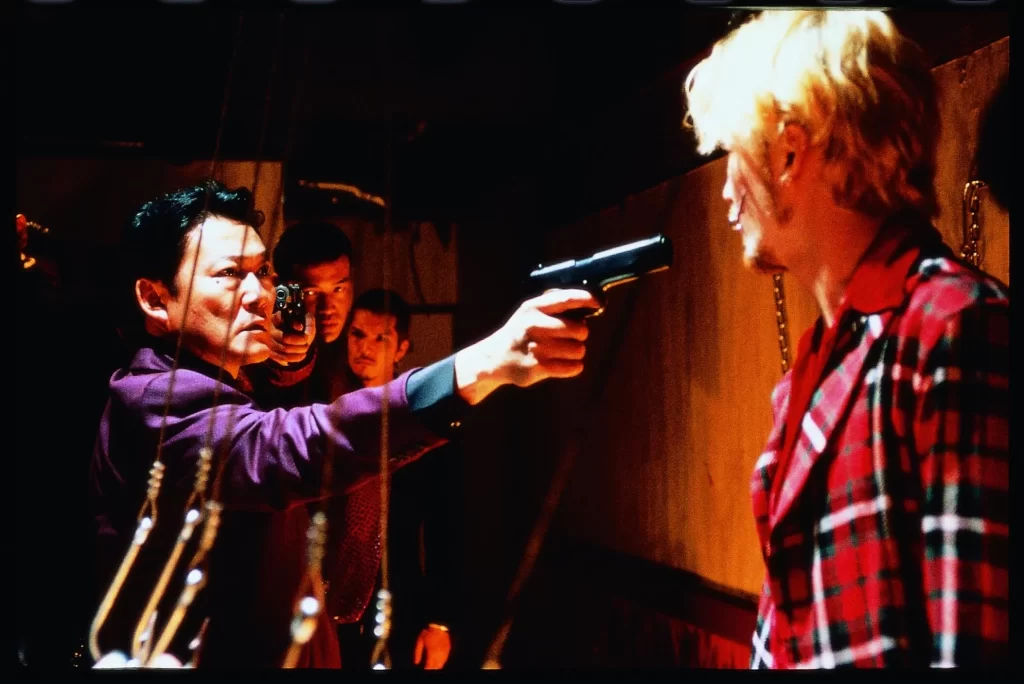

Poor Ichi (Nao Omori) doesn’t like killing. He’s a loser incel who can’t differentiate between arousal and murderousness. When he kills a local mob boss, shredding his organs from his body, it sparks a chain of vengeance and confusion that leads all the way to the upper ranks of the Yakuza underworld. Kakihara (Tadanobu Asano), the dead boss’s enforcer, is a monstrously sadomasochistic henchman with slits in his cheeks that allow him to open his mouth wider like a snake. In the mysterious Ichi, he sees both a rival and a kindred spirit, united in bloodshed and organ removal.

Miike makes all of us perverts and voyeurs through Ichi the Killer, like a Michael Haneke who thinks stoicism is a waste of time and restraint is for people without knives in their shoes. In one scene, a loser goon is attached inside a TV set, acting as both entertainment and spectator. Close-ups on torn flesh and intestinal puddles make even the Yakuza faint. It’s all gloriously over the top, a manga come to life where blood sprays in every direction and nobody is safe.

A lot of the violence is patently silly, such as when Ichi slices a man in half from head to toe. The CGI, which feels like Playstation cutscenes, looked terrible at the time. But other scenes are horribly real, like the tongue removal and ripping off of one character’s cheeks. Women in particular suffer at the hands of these grotesque men (the rape and brutality of women, mostly sex workers, in the film has faced much criticism, and not unfairly). Ichi saves one woman from being killed by her pimp, only to murder her himself when she rejects his faux-heroic advances. His murderous instincts are driven by a convoluted brainwashing scheme rooted in a planted memory regarding an abused teenage classmate he feels he wasn’t able to save. Now, he slaughters on demand, incredibly skilled at a thing he hates.

Violence is simply all these men know. There isn’t a single man who isn’t tainted by its memory or actively engaging in it. Violence is also the only thing they respect. When Kakihara is expelled from his gang, he immediately gains control over the entire organization because everyone else in the group is in awe (and terrified) of his abilities. He enjoys hurting and being hurt. “There’s no love in your violence,” he drolly tells one goon who is in the middle of beating him mercilessly. In Ichi, he hopes to find someone worthy of his murder, but such a search is doomed to end brutally for all involved.

A lot of Ichi the Killer is surprisingly funny. You laugh at the nonsensical biological confusion of it all as limbs bend backward and bodies stay perfectly still on sliced-off legs until they slip off like something from a Wile E. Coyote trap gone wrong. Unlike Audition, a Miike film where torture is an inescapable hell wrought by a madwoman with piano wire, Ichi the Killer (and to an extent Visitor Q) have one foot firmly in parody as well as the real. That does provide some serious tonal dissonance when it comes to the rape scenes, although it could be argued that this was the point: you could make violence funny but not rape, which says a lot about both film and the culture at large.

Miike made many violent films after Ichi (including an episode of Masters of Horror so shocking that Showtime never aired it), but this is the one that has become infamous. It’s not hard to see why a film about an incel and a pervert going head-to-head for cartoon-esque hypermasculine supremacy would resonate with modern audiences. The cycle of violence goes on, and it is both highly grotesque and deeply stupid.

“Ichi the Killer” is streaming on Kanopy, Hoopla, and Tubi.