Four movies deep and 20 degrees down, my brother and I were the last ones left at the Aut-O-Rama Twin. The only other survivor — a hardy family piled in and around a pickup truck — must’ve bailed while I was in the bathroom. When I shambled out of the brick bunker, under the red humming MEN’S sign, there was just a familiar Chevy out in the dark.

The cold already found the cracks in my well-meaning, woefully inadequate armor. It was around three on a late October morning, but that was no excuse for a temperature faltering in the upper teens. My Pendleton sweater and worn-out jeans were only fashion statements by the time my feet touched gravel.

We parked near the front, naturally, because drive-ins play by different rules than theaters. It helped that my brother and I approached the annual Halloween horror marathon as we did all drive-in excursions, with delirious, often detrimental zeal. Park as close to the screen as possible. But it’s a long walk to the concession shack and, at best, 35 degrees. No worries, though, ‘cause that’s what the bottomless fresh-brewed coffee (great by drive-in standards and good by any others) is for, even if we have to trek through the cold to get it in the first place. And you best believe we still got ice cream between movies two and three on principle.

But by the closing minutes of the last leg, the coffee was gone and everything warm was locked up but the bathroom. All that remained was our car, the monolithic screen, and me, staggering over the lunar surface of our local drive-in.

Then came the snow. Nothing heavy. I only noticed it in the projector’s unblinking eye.

Then muffled screams of a madman. Louder as I marched the last few rows to the car. Fighting the stringy sounds of an orchestra about to witness a murder. Interrupted with a shout.

“Danny Boy!”

I stopped and looked at the screen.

Jack Nicholson was huffing and puffing and stalking his son with an ax through that frostbitten hedge maze. There couldn’t have been more than a few minutes left.

I watched him shiver, alone, severed from the natural world, and wondered when I’d crossed my arms like his.

For a chilling moment, as the only sign of life at the Aut-O-Rama Twin, in the godforsaken hours of an October morning, shaking from the cold, I was in The Shining. And that’s why my heart will always belong to the drive-in.

Modern movie theaters are designed like sensory deprivation tanks. Sound systems that intelligently scatter hundreds of channels to a dozen speakers. Better recliners than most people have in their homes. Excepting the human element, theaters are built toward one purpose: showing movies, distraction-free.

But drive-ins are distraction. That unseasonable breeze. Applauding honks from passing semis on the interstate. Rear-view mirror peeks of the double feature playing across the lot. Listening to the crickets on your way to the concession shack. You can even fiddle with your phone and yell at your friends with reckless abandon. Drive-ins share as much DNA with the multiplex as a summertime bonfire.

Drive-ins began as a means to get people out of the house but not out of their shiny new cabriolets. As a car-parts salesman in the 1930s, Richard Hollingshead watched America fall in love with its automobiles in real time. Contemporary surveys told it best: The general public cared more about their cars than houses, telephones, basic hygiene or electricity. So when Hollingshead started rigging up a sheet between two trees in his driveway for his plus-sized mother to watch movies away from the cramped grindhouses, it didn’t take long for him to patent the idea.

On June 6, 1933, the first drive-in opened in Camden, N.J. By the 1950s, they numbered over 4,000 across the country. Nobody could have guessed at the time, but that’s as many as there’d ever be. At its peak, the drive-in offered something you couldn’t get at the local theater, even if that something was usually table scraps.

The format hasn’t changed — two movies to a screen, once a night, from Memorial Day to Labor Day. That’s a neat evening to you and me, but a waste of time to studios, who’d rather send their big, flashy pictures to a theater that can show it a dozen times a day. Even at the height of the drive-in, they had to make due with B-movies and gently used prints of last summer’s A’s. But to their credit, drive-ins thrived on those leftovers.

The Beast With 1,000,000 Eyes! Battle Beyond the Sun. I Was A Teenage Werewolf. Lurid, loony masterpieces from exploitation masters like Roger Corman kept a steady supply of teenagers and their parents’ cars rolling in. If the shlock didn’t pass muster, they’d either vote with their headlights and wash out the projection or turn their attention to sucking face in the backseat.

But those backseats got smaller. And the trashy lifeblood that made drive-ins a cornerstone of adolescent sociology made families think twice about coming back. The 1970s oil crisis shrank vehicles of every make and model, killing the very reason Hollingshead hung up his sheets in the first place. The bloodless charms and rubber arms of 1950s creature features gave way to the campy gore of Death Race 2000 and counterculture degeneracy of The Wild Angels. Parents would rather stay home and let the kids watch television. Even the B-movies hit the road for greener, cheaper pastures on home video.

Drive-ins soldiered on until they met the single most nefarious force of the 1980s: strip malls. So much for 4,000 drive-ins.

Today, there are about 400 left. But that number’s not as tragic as it may sound.

The modern drive-in gets the same movies as the neighborhood 10-screen. Not as many, obviously, and not as long, and not that some studios understand the difference. Last summer, Disney demanded higher rental fees and longer bookings from drive-ins for Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2, and also tried to dictate which film would play as the first part of the double feature (Disney nature doc Born in China). The drive-ins refused in a show of solidarity strong enough to make Disney flinch. Accepting the terms would have necessitated price hikes on everything from tickets to Twix bars, and that’s suicide for any small, family-owned business.

Those 400 drive-ins will probably be around a while. They’ve found their groove as living pieces of nostalgia. Considering the alternatives, $10 for two movies is no hard sell. It may not come with central air, but they make up for it in atmosphere.

Every entrance to the concession shack at my local drive-in is marked in neon green, with a sign that promises this Refreshment Area was once sponsored by 7-Up. I don’t know when that might’ve been, but stepping inside provides clues. Brown shingles hang over the grills and fryers, a fake edge for an indoor roof. Homemade hamburgers, fries and delightfully ambiguous “poppers” are cooked up under the watchful, misshapen eyes of off-model Disney characters cut out of plywood. Pinocchio wears more purple than you might remember and that’s either Yogi Bear or Baloo with a porkpie hat, but they’re something charming to stare at while you’re waiting for a fresh pizza. And when you do get that steaming slice, it comes with a “sorry,” a “please enjoy” and a “have a nice night” from someone in an Aut-O-Rama shirt you can buy for $15. It’s a family operation from the ticket booth to the candy rack and you’ll see it shine through in even the smallest interactions. And dammit, the food’s good. Better than the multiplex equivalents that cost an extra pint of donated plasma. Better still when you’re eating it on a squeaky lawn chair under the Technicolor glow of a cartoon hotdog doing tricks for a cartoon bun. They don’t make intermission countdowns like they used to. They don’t make them at all, really.

Like drive-ins. All the friends I’ve badgered into joining me have stories — like their own local drive-in that closed when they were too little to see over the dash — or at least a long-standing curiosity. Usually what seals the deal for them isn’t the featured movies or my charming companionship but the mention of drive-in calamari. Nothing makes them wince quite like that phrase, a perfect cocktail of allure and alarm. The Aut-O-Rama Twin hasn’t served it in several summers, but I have indulged in a basket of their fried squid and, if given the chance, I would do it again. And without fail, those friends, no matter how shellshocked, always ask the same, excited question when we step under that green 7-Up sign: “Where’s the calamari?”

Lack of seafood aside, they’ve never walked away disappointed. I took a date to a risky double-feature of recent comedies and the opener was a complete wash. That’s nine dollars and two hours of joyless silence at the Regal down the street, but not at the drive-in. We talked and joked and told ghost stories until it was over, checking in now and again to tally the college comedy clichés. Last summer, a few buddies and I staked out prime parking spots for a marathon of the entire Back to the Future trilogy. The great train robbery finale of Part III landed somewhere around 4 in the morning, when our enthusiasm had mostly dried up and the chocolate truffle sundaes had entirely turned against us. We needed a miracle. We got a train, roaring down the tracks along one side of the drive-in. Its thunderous applause almost shook us out of our lawn chairs, but we didn’t mind. It’s one thing to watch the end of Back to the Future Part III, but it’s something else entirely to see it spill off the screen in the corner of your eye, hear it hurtle past in a half-deafened ear and feel it rattle into your bones through your tattered Skechers.

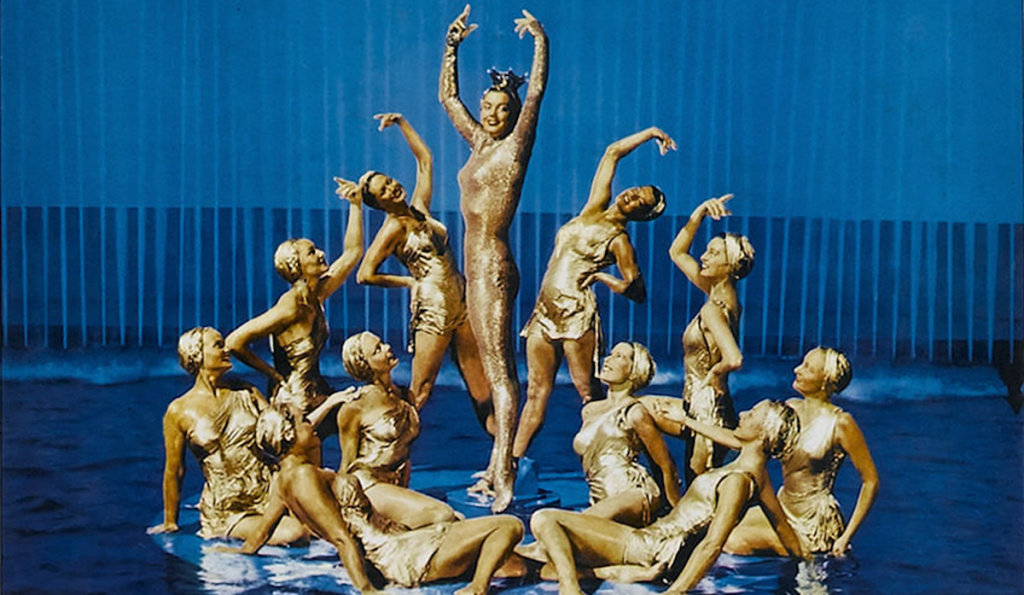

As of today, the American drive-in is 85 years old. In all that time, the experience hasn’t changed. It’s still a night at the movies with a little extra character. They’ll never number in the thousands again, but they don’t have to. They’re a piece of living history cleverly disguised as parking lots wedged between big, white walls. You could make a clever comparison to the evolution of cave paintings, mythic stories painted on big, brown walls, but that just wouldn’t feel right. Drive-ins are too fun for anything that academic. And if you’re thinking about it too hard, you’ll miss the intermission cartoon where the soda pops do a synchronized tap routine.

I try to sell a trip to the drive-in to anybody who enjoys movies, summer nights, good times or the amorphous concept of joy, but there’s no need to rush. The patron saint of drive-ins, critic and former MonsterVisionary Joe Bob Briggs, said it best with the last line of his aptly titled Drive-In Oath:

The drive-in will never die.