In the 1960s and early 1970s, long before home video or the Internet, fandom for comic books, horror movies, and genre television series was growing. But aside from conventions and home-mimeographed fanzines sent by mail, fans had little contact with other fans. Those of us who loved the genre were alone in geek clubs with a membership of one – unless you found a neighbor or classmate who shared your obsession with Boris Karloff movies or Star Trek. Letters pages of comic books were alone in giving readers an idea of who else was out there with the same interests.

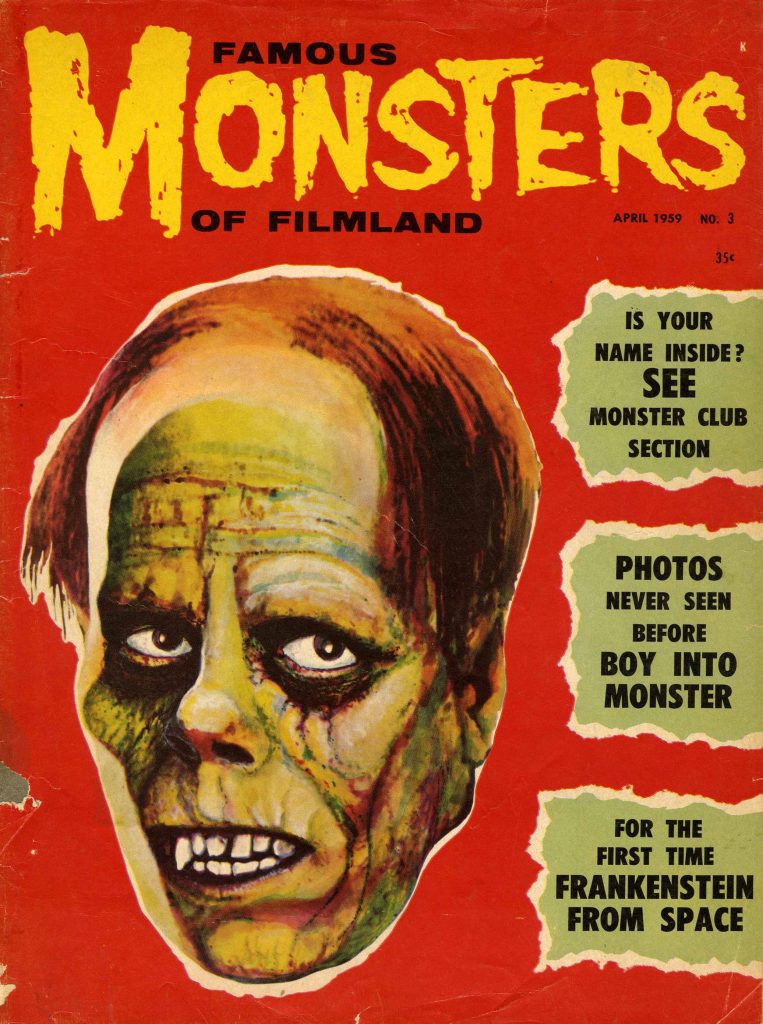

Now, of course, horror and science fiction and superhero stories permeate mainstream pop culture. But 50 years ago and more, we got our fix and found those like us where we could find them with convention screenings of a film on actual film stock, late night reruns on TV, and magazines –especially Famous Monsters of Filmland. FM was created by publisher James Warren and editor Forrest J Ackerman to capitalize on the “Shock!” package of vintage horror films released to television in 1957, the year before FM debuted. FM was known for cultivating young fans, who wrote in and grew up to become filmmakers like Joe Dante and Steven Spielberg. But Famous Monsters was sometimes dismissed as puerile because of its silly puns.

A few other magazines, and a single newspaper, gave us some insight into the genre we loved. They did so with fewer puns (in most cases) and articles pitched at slightly more mature readers. And by their very presence, they proved to us that there were others out there like us.

It’s likely that the magazine Castle of Frankenstein was the first mainstream attempt to mine the monster movie interest that Famous Monsters capitalized on. CofF began in 1962, four years after FM, and was undeniably more “adult”; the articles were more serious and, before it ended in 1975, partially nude pictures of Hammer Films actresses like Ingrid Pitt were included. That type of photo would never have been published in FM, but Castle of Frankenstein’s coverage reflected the rise of Hammer and its color versions of classic horror characters like Dracula and Frankenstein – films dotted with blood and nudity.

CofF boasted an unusual publishing lineage. These days, publisher Calvin T. Beck would be better known now as the son of C.C. Beck, who created the comic book character Captain Marvel (now known as Shazam). For most of its run, CofF was edited by Bhob Stewart, a writer and cartoonist who, in 1953, created what’s recognized as the earliest fanzine devoted to horror and other comics from EC. Stewart was ubiquitous in fan circles for decades and his resume includes not only CofF but the creation of those “Wacky Packages” parodies of commercial products.

FM’s Warren and Ackerman launched one-shot, one-movie-focused publications during the 1960s, but published nothing odder than Monster World, a 10-issue variation on Famous Monsters that came out from 1964 to 1966. How much like FM was Monster World? When Monster World wasn’t a hit, Warren incorporated its 10 issues into the run of Famous Monsters, allowing the 100th issue of FM to arrive a little sooner.

All the Warren magazines and CofF were printed on cheap paper and were mostly black and white inside, but the genre’s glossiest competitor arrived in 1970. Cinefantastique, edited and published by Frederick Clarke, was a serious-minded magazine that featured lengthy interviews with filmmakers and in-depth articles about the movie on that month’s cover. Cinefantastique, defying the odds against publishing a relatively pricey genre magazine, lasted into the 2000s.

But the strangest monster magazine format was still to come, and it wasn’t a magazine.

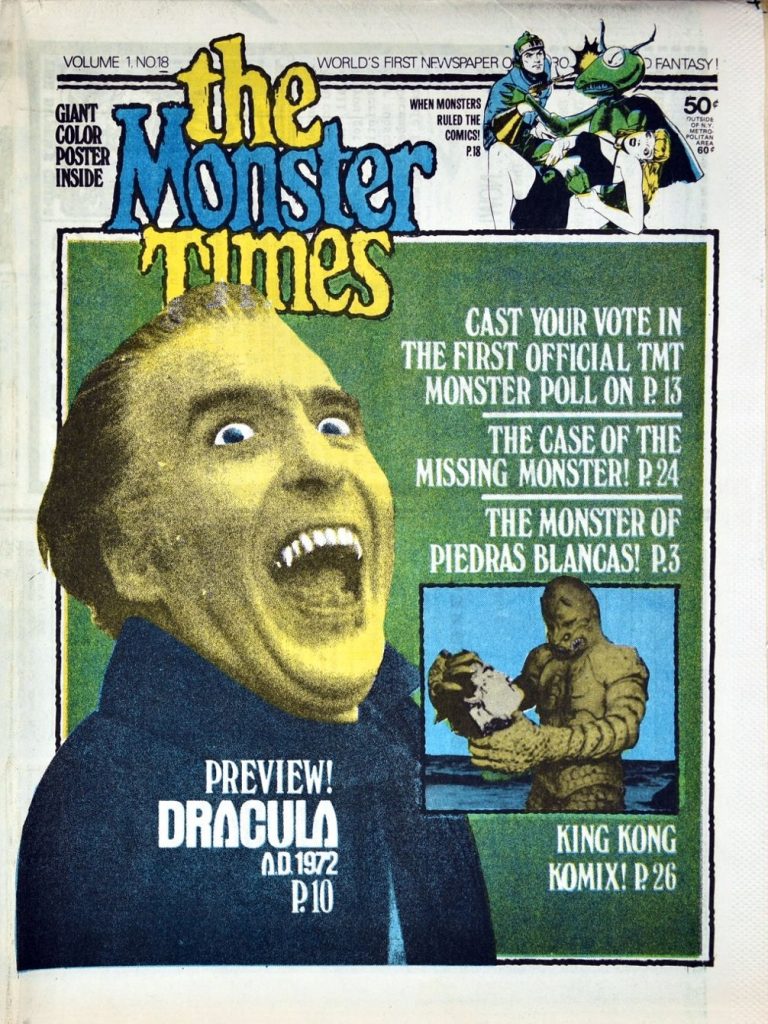

The Monster Times, published from January 1972 to July 1976, was created by a group of publishing industry veterans and laid out by the designers of the infamous SCREW sex industry tabloid. The Monster Times was meant to challenge Famous Monsters; other magazines, notably Castle of Frankenstein, had tried to do that before.

Like CofF, TMT took a more adult approach than Famous Monsters. The puns that made older readers of FM wince were considerably toned down, and the humor that was employed was more sarcastic – but still punny. To me, growing up in Indiana, The Monster Times seemed “big city.”

TMT was distinguished by more than its adult approach. The tabloid newspaper format looked different than anything else on most newsstands. TMT came folded as if it could be tucked under an arm as you waited for a bus; after you perused the blurb-filled cover, you would unfold the newspaper and see something of a second cover, a full-page illustration and some verbiage that tipped to an article or two inside.

The first issue was the kind of nostalgia-fest that readers had, over more than 10 years, grown to expect from FM: The newspaper focused on classic films and entertainment, with a cover story on the original 1933 King Kong as well as Nosferatu from 1922 and 1915’s The Golem and the comic strip Buck Rogers. The “centerfold” illustration in that first issue presented the kind of art that set TMT apart: a full-page illustration by masterful artist Bernie Wrightson, depicting the Boris Karloff version of the Frankenstein Monster.

The rest of the issue focused on fantastic film visuals, with an illustrated adaptation of Nosferatu followed by more articles on classic films like Things to Come. There are some forward-looking elements, including “The Monster Times Teletype” – the name itself harking back a hundred years – that was the place for news about upcoming films like Frogs and the sequel to The Abominable Dr. Phibes.

True to its newspaper nature, TMT included classified ads, where readers could sell genre merchandise. Most offered still photos, comic books and posters, but one was from a collector of a different stripe: “Attractive teenage comix/sci-fi/fantasy loving girls; your letters will be welcomed by …” and included the name and address of a man in Illinois. (A Google search of the man, including his very unusual first name, indicates he’s still active.) A calendar of conventions, growing in popularity in the early 1970s, further reinforced the feeling of community.

The Monster Times followed this pattern, with a few variations, each of its 50 or so issues, but downplayed the 1920s and 1930s classic genre films and zoomed into the latter half of the 20th century – or maybe the 23rd century — with its second issue, which was almost entirely focused on Star Trek. Issues to come followed that mix.

I’m not sure why TMT ended, other than the fact that a lot of ostensibly better-funded Hollywood magazines ran out of gas. A combination of problematic circulation – it was not as easy to find on drugstore and newsstand magazine racks as FM – low revenue, and reader aversion to the newspaper format might have killed the magazine industry’s most interesting attempt to capture horror and sci-fi fandom.

The monster mags wound down in the years that followed, but they served their purpose to fans at the time. They gave us some information, some nostalgia, and a sense that we were not alone.