In the early days of hip hop, the nascent genre had a visual counterpart in graffiti culture. Just as the spare production and thick-to-the-point-of-distortion bass and drums of early rap singles cut through the dense, cocaine-trebly rock music of the 1970s, the large, colorful tags on NYC subways demanded the attention of its viewers. Large-scale taggers sometimes evoked and parodied fine art, the way DJs sampled others’ songs in their sets. Graffiti crews’ willingness to work outside the law paralleled outlaw narratives in songs like “White Lines (Don’t Do It).”

Unlike the early days of hip hop, which was reasonably well documented, graffiti is an ephemeral art form, and the work of many influential taggers has been lost to time and to anti-graffiti initiatives in New York and elsewhere. Two filmmakers, documentarian Tony Silver and experimental director Charlie Ahearn, depicted the art form and its intersections with breakdancing and first-wave hip hop culture.

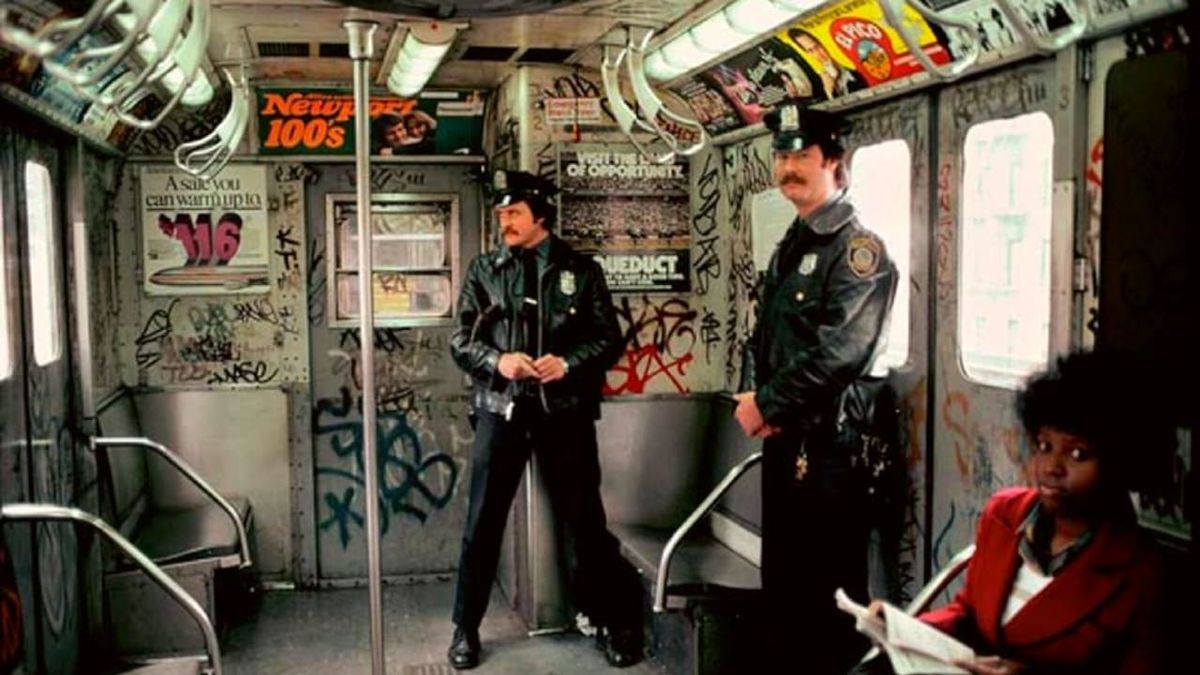

Tony Silver’s Style Wars serves as an overview of graffiti culture in 1982. The film offers a comprehensive view of street art, with its crash course on midcentury taggers like Taki-182 and the way it foregrounds the creative process of the different graffiti crews working in the Bronx. While Silver is on the taggers’ side—as shown in the gorgeous shots of bombed-out graffiti trains that bracket the film—he interviews a wide swath of New Yorkers who are both sympathetic to and antagonistic of the graffiti tags that dot the subway walls.

Tagging trains, especially with the elaborate bombs that the taggers in Style Wars favor, was a risky venture in pre-gentrification New York, and Silver includes many of the hazards his writers would experience. An early sequence shows one crew opening an electrical panel on the sidewalk and walking down a vertiginously narrow staircase to get to a train yard. Talking head interviews are woven throughout the running time, most notably from longtime NYC mayor Ed Koch, who began an anti-graffiti campaign as the film was in production. In one of the most poignant scenes, 17-year-old tagger Skeme—whose end-to-ends traveled through all five boroughs on the 1 and 3 trains before he was old enough to vote—is interviewed alongside his mother, who dismisses his achievements with a blank stare and a hollow laugh. The concerns she expresses are understandable, but her unwillingness to engage with Skeme’s pride and achievements gives this scene an all-too-relatable sadness.

While Silver shows the dangers of graffiti tagging, he also portrays the fulfillment graffiti writers get from their chosen art form. In an early scene, his camera lingers over one tagger’s black book, showing the evolution of his tags. One extended sequence opens with a crew meeting at a street corner to throw up a burner under the tutelage of an experienced writer, and climaxes with a single time-lapse wide shot of the piece as it’s completed. An unidentified white woman approaches one of the younger crew members to ask about the piece, and their conversation offers a good explanation about the positive effect graffiti can have on art fans and the community around them.

Towards the end of Style Wars, the work of several writers is selected for inclusion in a show at a posh Downtown gallery. Both the writers and the fine art collectors have strong opinions about graffiti being recognized as a legitimate art form. Wild Style, a feature film set in the Boogie Down Bronx, depicts the tension between art and commerce as tagging attracted the interest of the gallery scene.

Raymond (graffiti writer Lee Quiñones) is an enigmatic presence on the graffiti scene. He’s thrown his Zoro tag on a few trains that have traveled throughout the city, which has earned him the respect of the graffiti crew The Union, who haven’t met him. As The Union gains some mainstream recognition, Zoro’s identity is revealed and he is positioned as a possible art world star.

The scripted narrative stretches of the film feel like an attempt at extending the concert and graffiti footage into a feature film. Ahearn and Fab 5 Freddy’s script is a series of contrivances that maneuver their protagonists from Point A to Point B, and much of the screenplay involves the characters reciting plot points to one another. Ahearn doesn’t get credible performances from his cast, some of whom have had great screen presence in other projects, and the trite dialogue and wooden line readings seem like something out of an After School Special.

Wild Style is at its best when focusing on the graffiti and hip hop scenes. Like Style Wars director Tony Silver, Ahearn delves into Raymond’s creative process in a way that feels grounded in reality. The opening scene finds Raymond risking his life to throw his tag on a train car in the yard, and watching Quiñones paint Zoro tells us more about the character than any of the dialogue in later scenes.

While Style Wars establishes a more impressionistic connection between the graffiti and hip hop worlds by intercutting scenes at breakdance competitions with shots of writers tagging trains, Ahearn makes a more explicit connection among the two subcultures. Rappers show up in cameo roles, and Ahearn and editor Steven C. Brown skillfully transition between scenes at concerts and breakdancing bouts and scenes with Raymond and The Union throwing up tags. It all builds to a crescendo with a concert by Chief Rocker Busy Bee and DJ AJ at an amphitheater that Raymond tagged; as the music reaches its climax, Raymond scales the rim of the amphitheater to watch the show, taking great pride in his latest mural.

The Bronx has been gentrified in the 50 years since the birth of hip hop, and the vacant lots and abandoned buildings visible from the New York City subways in Style Wars and Wild Style have been replaced with luxury high-rises and overpriced condos. Directors like Tony Silver and Charlie Ahearn had the foresight to document this fly-by-night culture, and their films are an essential document of the early hip-hop scene for art fans and rap fans alike.

“Style Wars” and “Wild Style” are streaming in the Criterion Collection’s “Hip Hop” program.