Murderinos, rejoice: A retelling of the Boston Strangler killings has premiered on Hulu. In Boston Strangler, reporters Jean Cole and Loretta McLaughlin break the story of the murders in The Boston Record American, coining the killer’s name and tracking down leads as the Massachusetts State Police Department repeatedly botch their investigation. Foregrounding the experiences of the female reporters who brought news of the murders to the general public allows writer/director Matt Ruskin to explore some themes of importance to contemporary true-crime enthusiasts, such as the failures of the carceral system and the casual sexism many professional women experienced.

Fifty-five years prior to the release of Boston Strangler, 20th Century Fox released the feature film The Boston Strangler, which depicted the investigation from a more standard point of view. Like its 21st century counterpart, the 1968 feature reflected some of the mores of the time—such as a mildly ambivalent attitude towards law enforcement—and its free-associative editing and depictions of violence predict the New Hollywood movement of the 1970s.

By the time The Boston Strangler went into production, news of the murders and of DeSalvo’s imprisonment had made national headlines for several years straight, and Gerold Frank’s book about the murder had made the New York Times bestseller list. Director Robert Fleischer assumed his viewers knew about the crime, and instead of trying to impose a narrative, he establishes a mood of uncertainty and paranoia. The first act is a series of vignettes that alternate between the elderly female victims and the police force assigned to the case. Crime scenes are shot in dingy, overexposed shades of ivory and gray with momentary flashes of bright colors. The actors deliver their expository dialogue in loud, slightly mannered tones, and DP Richard H. Kline’s use of eye-level wide shots and slow zooms suggest cold opens from 1960s sitcoms. We never meet the victims of these early crimes, and beyond the shock and fear their neighbors experience, we don’t have much empathy for them.

If the communities in which the victims lived are depicted as pathetic, the Mass Police Department are initially conferred with authority they haven’t earned. Kline shoots these scenes at low angles, and the staties’ tidy appearances and naturalistic line readings, combined with the sober browns and blues and colonial decor of the conference rooms, would make audiences want to take them seriously. Edward Anhelt’s dialogue undercuts the authoritative way Fleischer presents the police force, as they casually suggest finding a mentally ill petty criminal on one of their beats and coercing him into signing a confession.

As the film settles into a rhythm, the victims and the two women who got away get more screen time. Most of these women are younger and more conventionally attractive than the pensioners whose bodies are discovered in the earlier scenes of the film; while this is true to the chronology of the crimes, it also speaks to the intrinsic ageism of mainstream media in the 1960s that only the younger, prettier women are given more screen time and depicted sympathetically. Sally Kellerman’s portrayal of the composite character Dianne Cluny, whose self-defense plays a role in her escape, makes the deepest impression; her slumped posture and hesitant stammer as she attempts to identify her assailant credibly show the trauma she experienced in her narrow escape.

As the film settles into a rhythm, the victims and the two women who got away get more screen time. Most of these women are younger and more conventionally attractive than the pensioners whose bodies are discovered in the earlier scenes of the film; while this is true to the chronology of the crimes, it also speaks to the intrinsic ageism of mainstream media in the 1960s that only the younger, prettier women are given more screen time and depicted sympathetically. Sally Kellerman’s portrayal of the composite character Dianne Cluny, whose self-defense plays a role in her escape, makes the deepest impression; her slumped posture and hesitant stammer as she attempts to identify her assailant credibly show the trauma she experienced in her narrow escape.

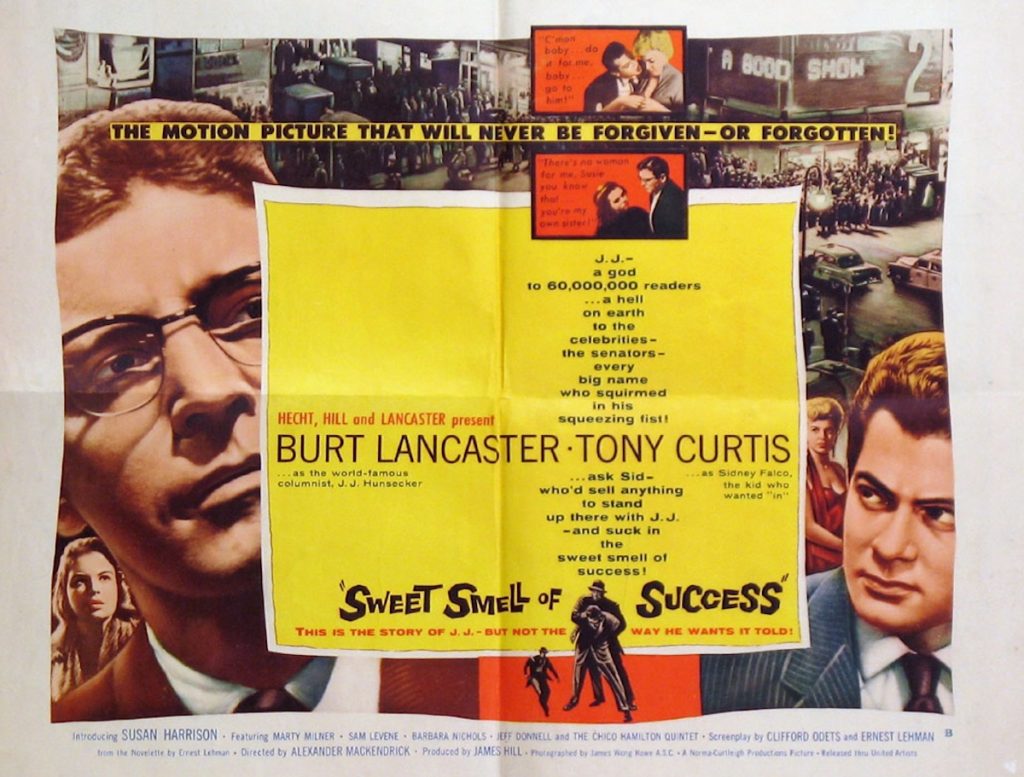

Like many contemporary true-crime movies and TV series, The Boston Strangler cast a movie star in its title role. Unlike most contemporary true crime antagonists, Albert DeSalvo was presented as a repellent human being instead of a sexy antihero. While Tony Curtis started his career as a teen idol and had a respectable career as a leading man, his career had started its downfall when he booked this role. Before we see Albert DeSalvo commit a crime, he looks like someone you’d cross four lanes of busy traffic to avoid; the harsh lighting and below-eye-level camera angles draw the eye to the actor’s jowls, glassy eyes, and creased, porous skin. Curtis frequently sits slumped over with his head in his hands, his thumb circling his nostril. While he brings an admirable restraint to the role of DeSalvo, Curtis has flashes of the grace and physicality you see in his earlier roles, as in a scene late in the film when he attempts to strangle his wife; watching him shift from jerky gestures to a gliding step as his face goes blank is believable visual shorthand for the dissociative identity disorder the film cites as the reason for DeSalvo’s murders.

The Boston Strangler was in production at a time when avant-garde European cinema had started to influence American directors, and the film shifts into a more experimental style that reflects this inspiration after Albert is taken into custody. Massachusetts Assistant Attorney General John Bottomley (Henry Fonda) insists on putting DeSalvo under hypnosis to find out whether he committed the murders. Fleischer shoots these scenes from DeSalvo’s perspective as Curtis gives a rambling monologue, the jittery visuals paralleling the images DeSalvo describes. The crime scenes are presented as tableau with Fonda standing in the corner, looking out at the audience and coaxing DeSalvo to keep talking. Marion Rothman edits the scene with a fast pace, using jump cuts and building suspense by intercutting fragmentary shots to emphasize the frenzy of DeSalvo’s inner monologue.

The 2023 Boston Strangler in some ways gives audiences a snapshot of what contemporary true crime audiences have come to appreciate—independent investigations, a healthy distrust for the police, and female friendship as a way to keep one another safe. While the depiction of the Mass staties as inept bumblers was a bit outre for a serious feature from a major studio, The Boston Strangler is a similar time capsule for 1960s true crime aficionados. It was a truthy summary of a crime that stayed in the headlines for years, and its use of avant-garde technique and credible performances allowed audiences access to the mind of a notorious murder. Those who enjoyed Boston Strangler and want to see a different perspective on the crimes would find something to appreciate in The Boston Strangler.

“The Boston Strangler” is streaming on Hulu.